The Rise of White Flour

By Ronald Ladouceur

In the first decade of the twentieth century, newly minted advertising agencies turned sooty downtowns into riotous polychrome adscapes. Unconstrained by regulation, promoters erected billboards on virtually every empty lot and painted ads on any building with an accommodating owner.

It was a shockingly immersive advertising environment, a low-tech Times Square in every American city. The intent was to create a market avaricious enough to absorb the massive quantities of goods pouring out of the country’s factories. In the process, promoters created something else entirely, a new national identity defined not by ethnicity, religion, or political affiliation, but by the capacity to consume. Though the evidence is fragmentary, surviving outdoor ads trace the development of purity as the brand positioning most likely to motivate, and a constricting concept of whiteness as its most profound legacy.1

Ghosts of the First Mass Medium

Brewers and tobacco producers had been painting multi-story ads on buildings in roughneck sections of cities since the dawn of canals and railroads. But it wasn’t until the late 1880s and early 1890s that outdoor advertising began to invade more “proper” urban spaces. In an unregulated environment, with an imperative to move great quantities of factory produced consumer goods, marketers pushed their advantage, and outdoor (or out of home advertising) quickly grew out of control. Large scale lithographic posters, first deployed by circus promoters, multiplied sometimes five billboards high at any intersection of human traffic and property owner consent, invading cities without constraint until the courts started reining in wild posting in 1917.2

The first generation of widely posted outdoor ads typically promoted products for working men, like beer and tobacco. But by 1900, promotions for consumer packaged goods targeting women began to dominate. This Liberty Tobacco ghost in Poughkeepsie, New York, which probably dates from the late 1800s, was overpainted with an ad for the National Biscuit Company’s (later NABISCO) Uneeda Biscuit in the early 1900s.

Most outdoor ads were printed on paper and adhered to a backer board in a standard sized frame, and nearly all have since decomposed and been lost.4 A few photo archives exist,5 but most are either random collections or albums created to document a particular brand’s displays or sign company’s work.

But so prolific were promoters that a significant number of the subset of signs that were painted on brick walls, what we today call “ghost signs,” still survive. A walking tour of almost any downtown or market district will typically surface a half dozen or more faded fragments. Well over 8,000 survivors have been documented.6

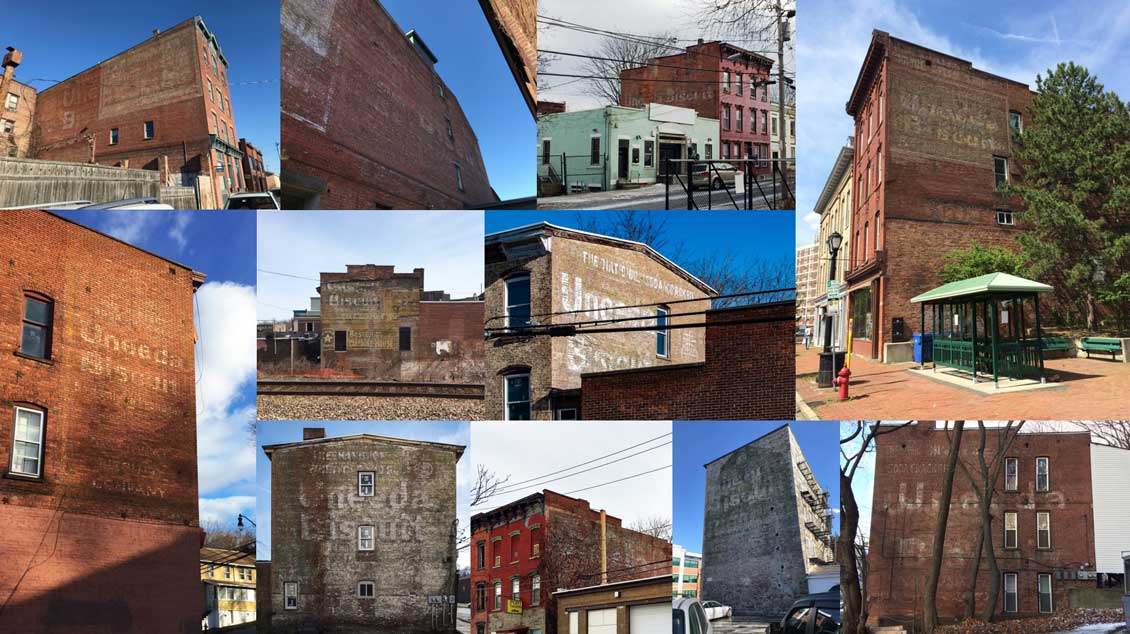

Launched in 1899 with a 10-year budget of $7 million, the National Biscuit Company’s Uneeda Biscuit campaign was the first to cover walls across the country. Photos: Albany, Cohoes, Kingston, Newburgh, Schenectady and Troy, New York; Lowell, Massachusetts.

The Dawn of Industrial Advertising

In 1899, the board of the National Biscuit Company authorized an expenditure of $7 million to promote its inaugural product, the Uneeda Biscuit. Within just a couple of years, the company’s advertising agency, N. W. Ayer and Son, had posted so many signs that an estimated 30 million people saw an ad for the product at least once a day.7

There were earlier “quasi-national” outdoor campaigns. Proctor and Gamble began advertising Ivory Soap in 1882, with outdoor probably part of its media mix by the mid-1890s. The earliest Coca-Cola brick face was painted in 1894 in Cartersville, Georgia, and new examples quickly spread from there. And many tobacco brands, including Bull Durham, Mail Pouch, Owl and Liberty, deployed outdoor extensively in this period.8

Early ghost signs often promised a functional benefit, typically a health benefit, connecting the new mass medium of outdoor to a patent medicine past. Photos: West Pawlet, Vermont and Holyoke, Massachusetts.

Nerve Tonics, Digestive Aids and Pick-Me-Ups

Messaging on the earliest surviving ghosts harken back to the era of patent medicines and snake oil salesmen. Virtually all consumer packaged goods (at least those not targeting dock workers) were pitched using some type of quasi-medical claim. Paine’s Celery Compound ‘made people well,’ Adam’s Pepsin Gum ‘aided digestion,’ and Coca-Cola, before it was ‘delicious and refreshing,’ ‘relieved fatigue.’

However, during the Progressive era, reformers and prohibitionists mounted attacks against dangerous ingredients, unsupportable claims and products, like Paine’s Celery Compound, that were mostly alcohol. Ironically, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 worked a miracle for marketers. Stripped of their ability to sell products based on functional benefits derived from consumption, marketers discovered a far more powerful strategy of positioning and promoting brands based on emotional benefits derived from acquisition and display.9

The development and promotion of one product more than any other illustrates the power of modern banding both to manipulate and exploit cultural anxieties, and relative to the thesis of this essay, define a cultural category and promote purchase by otherizing non-buyers.

Bread baked in a factory promised ‘purity,’ and grew softer, more uniform and tasteless as the twentieth century progressed. Photo: Madison, Wisconsin.

The Rise of White Flour

For centuries, mills had ground wheat and other grains using large flat stones. But stone grinding could only break off a wheat kernel’s bran layer. Its other two primary components, the white endosperm and dark germ, had to be ground together. Because of the oils in the germ, the resulting flour, though nutritious (most of wheat’s nutrients are in the germ), attracted insects and went rancid rapidly.

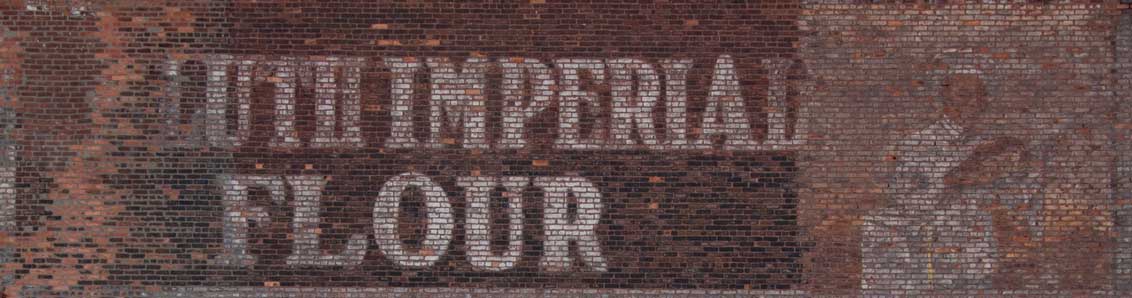

In the late 1870s, a new technology, cold rolling, made it possible for the first time to separate into independent processable streams a wheat kernel’s three core components. When coupled with mechanized farming, fertile western lands just recently cleared of their native populations, and a mature national freight transportation network, shelf-stable white flour began pouring out of the Great Plains in the 1890s, first from Duluth and its Imperial mill, and shortly after from Minneapolis, where the St. Anthony Falls powered the Washburn-Crosby ‘Gold Medal,’ Pillsbury and Ceresota mills.10

A major problem quickly surfaced. There was simply too much wheat, and consequently too much flour for the market to absorb. In fact, the grain’s overproduction is considered one of the main contributing factors in the Panic of 1893, the worst economic depression in the United States to that date.11

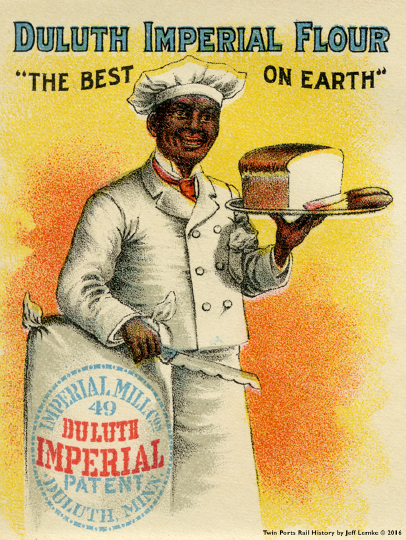

White flour, white oats, white bread, white cereals, and whitening soaps and detergents were among the brands most prolifically advertised in the early years of outdoor. White, in contrast to black, was promoted (and continues to be!) through use of racist tropes turned into product mascots. Other long-serving mascots, including the Quaker Oats man (left side above), the Uneeda Biscuit slicker boy, the Morton Salt umbrella girl, and Jell-O’s “little hostess,” symbolized innocence, purity and assured protection against contamination. Photo: Boston, Massachusetts.

White flour, white oats, white bread, white cereals, and whitening soaps and detergents were among the brands most prolifically advertised in the early years of outdoor. White, in contrast to black, was promoted (and continues to be!) through use of racist tropes turned into product mascots. Other long-serving mascots, including the Quaker Oats man (left side above), the Uneeda Biscuit slicker boy, the Morton Salt umbrella girl, and Jell-O’s “little hostess,” symbolized innocence, purity and assured protection against contamination. Photo: Boston, Massachusetts.

Milling Panic into Profit

Marketers had already figured out how to use racial anxieties to sell soap, tobacco and many other products.12 As the country tried to come to grips with a rending civil war that implicated not only Southern cotton producers, but also Northern mill owners and merchants in 250 years of human exploitation, marketers became partners in advancing the myth of the Lost Cause, which recast the plantation as a place of white idyll, where happy black slaves gratefully served their masters.

The earliest brand “mascots” included multiple examples of the “Mammy” and “Tom” tropes, icons that symbolically served as staff in middle-class homes and reinforced the social order.13 The Duluth Imperial Flour “Chef” served as the brand’s marketing mascot for only a decade or so (see image at the top of this article), but his near-identical twin still promotes Cream of Wheat.

But the use of ads exploiting overt racism directed at African-American and Native American populations faded as marketers figured out they could sell wheat, or anything else, by tapping into more metaphorical worlds of anxiety, a microworld of germs and genes and a menacing world of unregulated immigration. The implied promise was that through purchase, the consumer could distance themselves, physically and socially, from those things that potentially dirtied, or worse, labeled them. A simple loaf of bread, or any artisanal and locally produced food product, became suspect because the hands that crafted it were those of an unclean other.

In White Bread, author Aaron Bobrow-Strain explains:

Accurately or not, a simple loaf of bread from a small urban bakery seemed to many consumers a harbinger of death and disease … An urgent need to know that one’s bread was pure proved instrumental in convincing Americans to embrace industrially produced loaves. Early twentieth-century bread fears also confused food purity and social purity in a way that placed the blame for unsafe food on some of the food systems’ greatest victims and distracted attention from more systemic pressures, creating danger and vulnerability (emphasis added).14

Factories located on the edge of the recently “civilized” Great Plains were proudly and prominently illustrated in flour and bread-maker ads as places where food, untouched by human hands, particularly immigrant hands, was produced.

The Increasingly Generic White Ideal

If we count only ads for national products, rather than local products and simple wayfinder signs, more than 20% of ghosts still readable today promote white flour or a product made from it. In the Northeast, promotions for Duluth Imperial Flour, Ceresota Flour, Gold Medal Flour and the Uneeda Biscuit dominate the count. Gold Medal and Uneeda ghosts are among the only survivors that show evidence of multiple re-paintings. If we add in promotions for other white or whitening products – like oats, soaps and detergents – the scales tip even more toward white.

This layered ghost sign from Northampton, Massachusetts, promotes, in apparent succession, Uneeda Biscuit, Persil Oxygen laundry detergent, and Wrigley’s Spearmint Gum – all whitening agents, in one form or another.

Conclusion

In Northampton, Massachusetts, a surviving multi-layered ghost on a café on the corner of Bridge and Market Streets serves as a handy test for one’s willingness to entertain the claims of this article. On this prime location just a few blocks from the railroad station, the building’s owners contracted with national advertising agencies to paint, in quick succession between 1900 and 1915, ads for the factory-pure Uneeda Biscuit, the whitening power of Persil Oxygen Laundry Detergent and the digestive (and internally whitening) agency of Wrigley’s Spearmint Pepsin Gum.

This article’s admittedly provocative thesis may strike the reader as an overreach. Similar recent analyses focused on the development and defense of “whiteness” as a cultural category using an indirect data set have been poorly received. For example, a July 3, 2019 Washington Post review of an exhibit of the works of venerated illustrator and fine artist N. C. Wyeth by Philip Kennicott, which reviewed the works of Wyeth within the racist, eugenic and anti-immigrant environment of his day, drew nothing but scathing comments.15

While surviving ghost signs do unquestionably document the dawn of modern branding, their influence in defining and amplifying racial and cultural differences does require connecting the evidence to other primary and secondary sources, and even then, requires a good degree of “reading into” to support this story.

But if one accepts race as central to the story of the United States, the leap is not so great, and the opportunities are significant. As Victoria W. Wolcott effectively demonstrates in Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters,16 the American roadside was never a place separate from the underlying racial turmoil of its day. Places of public accommodation, particularly public pools, roller rinks and amusement parks were sites of significant political action in the decades prior to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. Conflicts expanded out from urban centers as freedom of mobility increased.

This Bedford, Pa. palimpsest is a survivor from a period when outdoor advertising was largely unregulated. Most printed billboards decomposed long ago. But many painted examples, what we call ghost signs, still haunt us. Encoded on their layered and fading faces is the story of the rise of national brands, and a critical shift in messaging away from individualized functional benefits toward communal promises of purity, conformity and acceptance through purchase. Photo: Bedford, Pennsylvania.

Most roadside enthusiasts are familiar with The Green Book and associated stories of the geography of segregation at hotels, motels and restaurants through the first six decades of the twentieth century (see Lyell Henry’s related article, “Accommodations ‘for Colored’” from the Fall 2005 SCA Journal). But this history is often treated as a parallel and non-intersecting intellectual highway. It strikes this author that the images and data collected by readers of this journal, so often documenting public accommodations and commercial amusements, would yield new and interesting understandings of the American journey through application of the traditional “scalpels” of history – class, gender and race.

About the Author: Ronald Ladouceur is a business owner, college professor, independent scholar, and a member of the board of directors of the Society for Commercial Archeology. He holds a B.A. in General Studies from the State University of New York College at Oneonta, and an M.A. in Liberal Studies from SUNY Empire State College. He is the principal and founder of POSTMKTG, a branding and marketing firm in Schenectady, N.Y. He teaches advertising at the University at Albany. And he maintains an academic journal at textbookhistory.com, where he has published more than 50 articles on the intersection of classroom science, popular science and public policy in the twentieth century.

Endnotes

1 This analysis is based partially on nearly 300 surviving “ghost signs” the author has documented, mostly in industrial cities in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania and Vermont, with a few additional examples from cities in the Midwest and Southwest United States.

2 All photos are from the collection of the author.

3 See: Baker, Laura E. , pp. 1187-1213.

4 So rare are printed examples of outdoor advertising that survivors can make the news when discovered. See: Brown, Evan Nicole. “A Wisconsin Bar Had an Enormous 1885 Circus Poster Hidden Within Its Walls.” Atlas Obscura, May 21, 2019.

5 See: https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/hartman/collections-and-guides/maxwell, which includes a 30,000 image archive of early outdoor advertising: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/outdooradvertising

6 With 8,000 examples and counting, Dr. Ken Jones has collected and maintains what is likely the largest collection of ghost signs in the United States. See: http://www.drkenjones.com/.

7 Baker, 2007.

8 Tobacco, unlike beer, could be transported and stocked without spoiling, a key factor in the development of national brands.

9 It is widely noted that among the first generation of advertising executives, a great many were sons of ministers. See: Kelso, p.24.

10 For a history of milling in the U.S., see: gage, 2006, pp. 84-92; Otis, 1893, p. 359; Roberts and Caron, 2003, pp. 308-319; Watts, 2000, pp. 86-97.

11 See: Hughes, 2012.

12 Though racist images on surviving hand-painted signs from this period are rare, as the medium did not lend itself to the reproduction of complex imagery (the image to the right is an exception – click for larger view), print ads for products as diverse as tobacco, soap and appliances promoted their wares by playing against black stereotypes. One need only Google “racist ads” to see numerous examples.

12 Though racist images on surviving hand-painted signs from this period are rare, as the medium did not lend itself to the reproduction of complex imagery (the image to the right is an exception – click for larger view), print ads for products as diverse as tobacco, soap and appliances promoted their wares by playing against black stereotypes. One need only Google “racist ads” to see numerous examples.

13 Aunt Jemima Pancake Flour famously used, and continues to use, its Mammy. Other “blacks,” which at the turn of the last century included Native Americans and Irish immigrants, were featured as caricatured foils in hundreds of marketing campaigns. See: Manring, 1998. Also see “Caricatures of African Americans.” UPDATE: The week this article was published, Quaker Oats announced it was discontinuing the Aunt Jemima brand. See “Why did it take so long to set Aunt Jemima free?“, Norris, Michele, Washington Post, June 17, 2020. One day later, B&G Foods announced it was reviewing its use of its racist mascot, Rastus. See “Cream of Wheat is reviewing its black mascot after Aunt Jemima and others acknowledged their racist roots”, Alcorn, Chauncey, CNN Busienss, June 18, 2020.

14 See: Bobrow-Strain, 2012, p. 19.

15 See: Kennicott, 2019. Typical (and most liked” as of July 12, 2019) was Jjmcmah1’s comment, which stated, “In my humble opinion Wyeth is a brilliant painter without an agenda and the writer is a politically-correct jerk.” Nearly all of the 189 comments that followed were similarly dismissive.

16 See: Wolcott, 2012.

References

Baker, Laura E. “Public Sites versus Public Sights: The Progressive Response to Outdoor Advertising and the Commercialization of Public Space.” American Quarterly, Vol. 59, No. 4 (Dec., 2007).

Bobrow-Strain, Aaron. 2012. White Bread: A Social History of the Store-Bought Loaf. Boston, Beason Press.

Brown, Evan Nicole. “A Wisconsin Bar Had an Enormous 1885 Circus Poster Hidden Within Its Walls.” Atlas Obscura, May 21, 2019.

gage, fran. “Wheat into Flour: A Story of Milling.” Gastronomica, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Winter 2006), pp. 84-92.

Hughes, L. Patrick. 2012. “History 1302: Agricultural Problems and Gilded Age Politics” (Course Guide).

Kelso, Tony. 2018. The Social Impact of Advertising. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Kenniccott, Phillip. “N.C. Wyeth painted the world full of beauty, resilience and adventure. And full of white people.” The Washington Post, July 3, 2019.

Manring, M. M. 1998. Slave in a Box. Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press.

Otis, E. L. “The Largest Flour Mill in the World.” Scientific American, Vol. 68, No. 23 (June 10, 1893), p. 359.

Roberts, Kate and Barbara Caron. “To the Markets of the World”: Advertising in the Mill City, 1880-1930.” Minnesota History, Vol. 58, No. 5/6, St. Anthony Falls: Making Minneapolis the Mill City (Spring – Summer, 2003), pp. 308-319.

Watts, Alison. “The Technology That Launched a City: Scientific and Technological Innovations in Flour Milling during the 1870s in Minneapolis.” Minnesota History, Vol 57, No. 2 (Summer, 2000), pp. 86-97.

Wolcott, Victoria W. 2012. Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle over Segregated Recreation in American. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2020, Vol. 38, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA