DR. PATRICK’S

NIAGARA RECAP

(Part I: Canadian Side and Conference)

By Kevin Patrick

All photos by the author.

The Society for Commercial Archeology (SCA) members from across North America were drawn to Table Rock to experience the splendor of Niagara Falls.

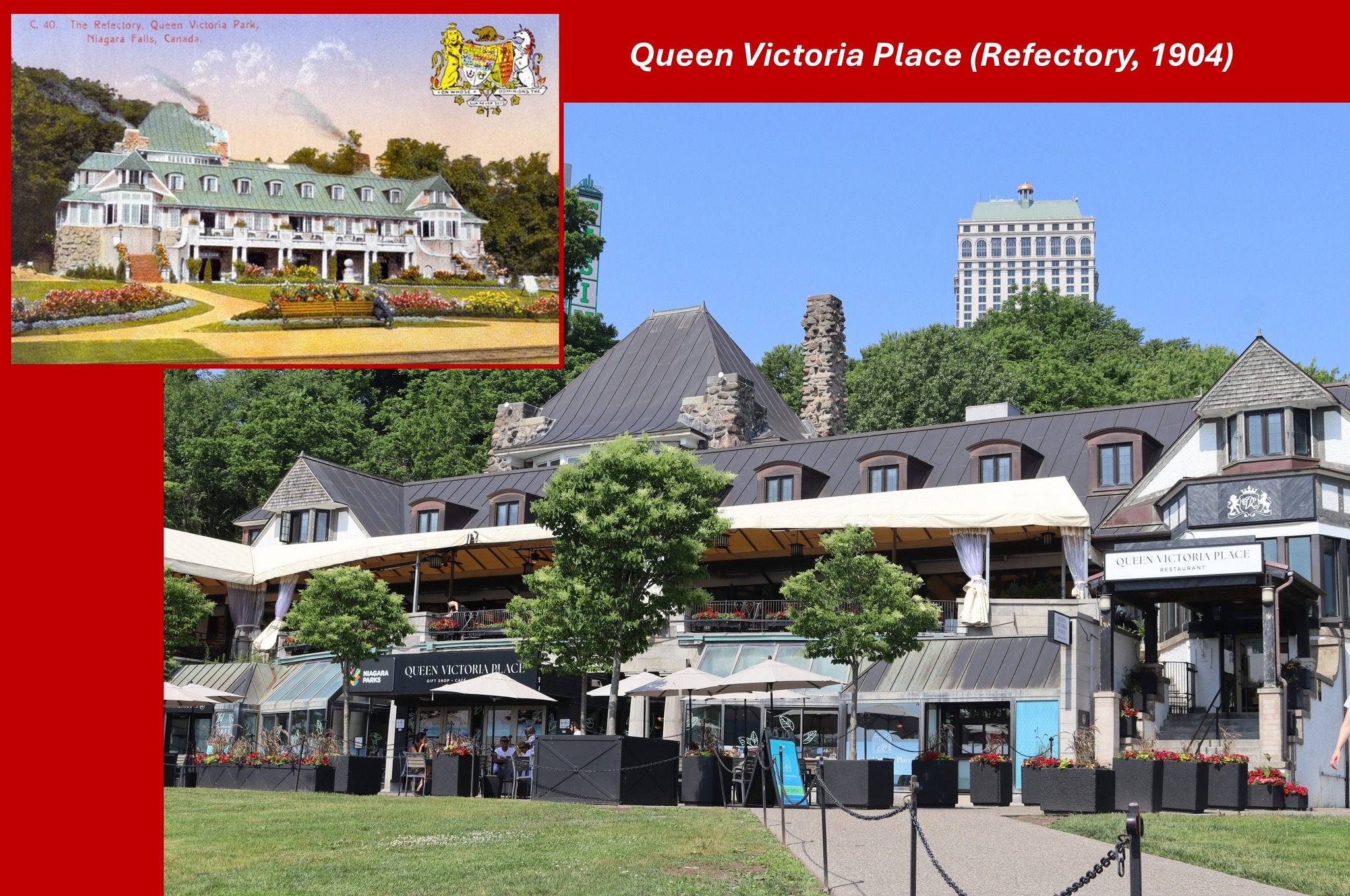

The SCA’s opening reception was held on the terrace at Queen Victoria Place, built in Queen Victoria Park as the Refectory Restaurant in 1904.

Travel writers complained that Niagara Falls was ruined by the rampant commercialization of the Canadian Front by the 1850s. In 1885, however, Goat Island and Prospect Point on the American side were enveloped in a state park designed in part by Frederick Law Olmsted. Following the same Central Park-like design inspiration, Queen Victoria Park opened on the Canadian Front three years later.

Queen Victoria Place, the SCA Niagara Falls Conference Opening Reception venue, is at bottom center in this view of Horseshoe Falls from the Skylon.

Opening Reception of the Society for Commercial Archeology’s first international conference Niagara Falls on the terrace at Queen Victoria Place Niagara Falls, Ontario.

Food, drink, and falls at Queen Victoria Place, Niagara Falls, Ontario.

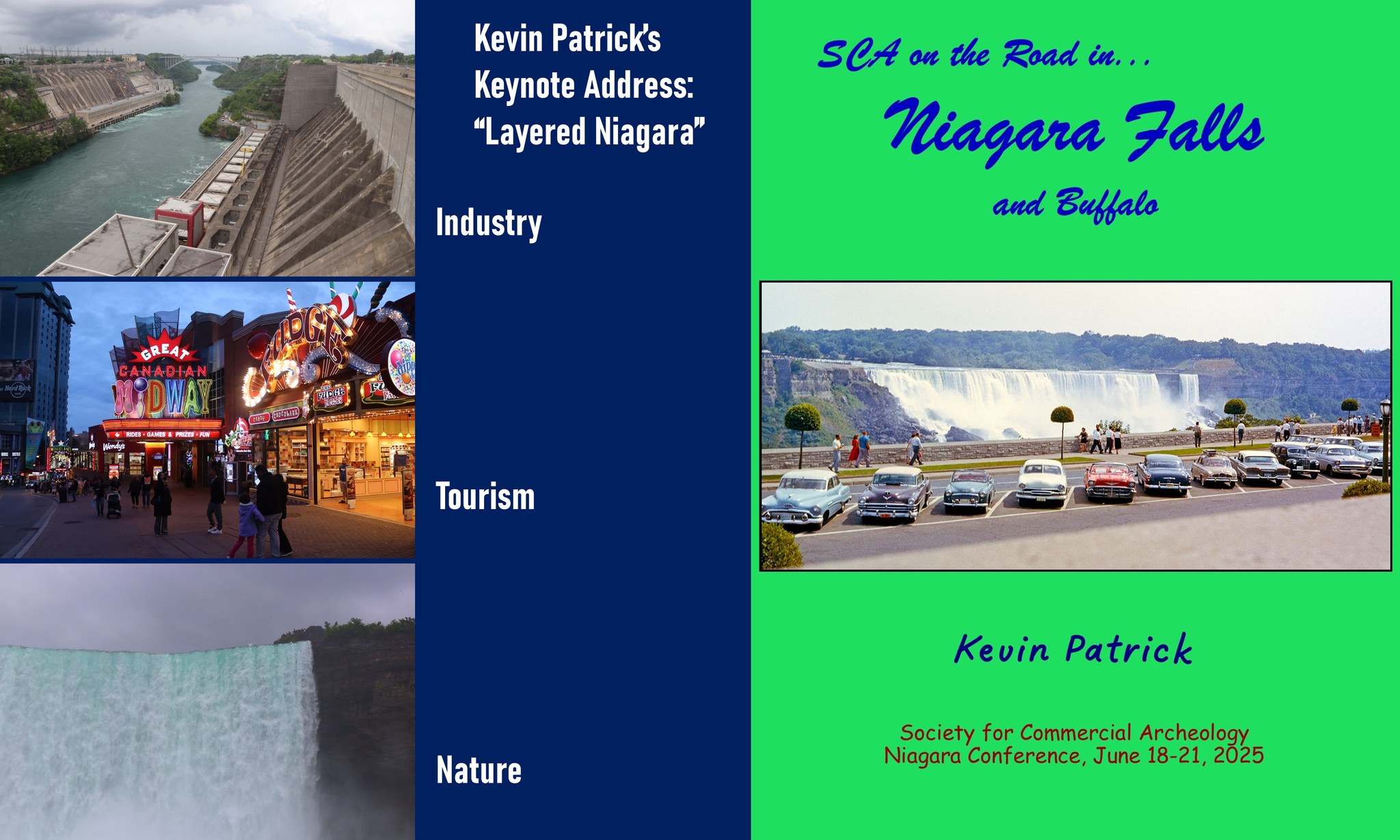

Landscapes related to Nature, Tourism, and Industry were interwoven into Kevin Patrick’s keynote address, “Layered Niagara” with an accompanying guide explaining two days of Kevin Patrick field trips. A few guides are still available…contact President Brian Gallaugher. Having to yell my presentation over the roar of Niagara Falls made this one of the most memorable venues I ever spoke at.

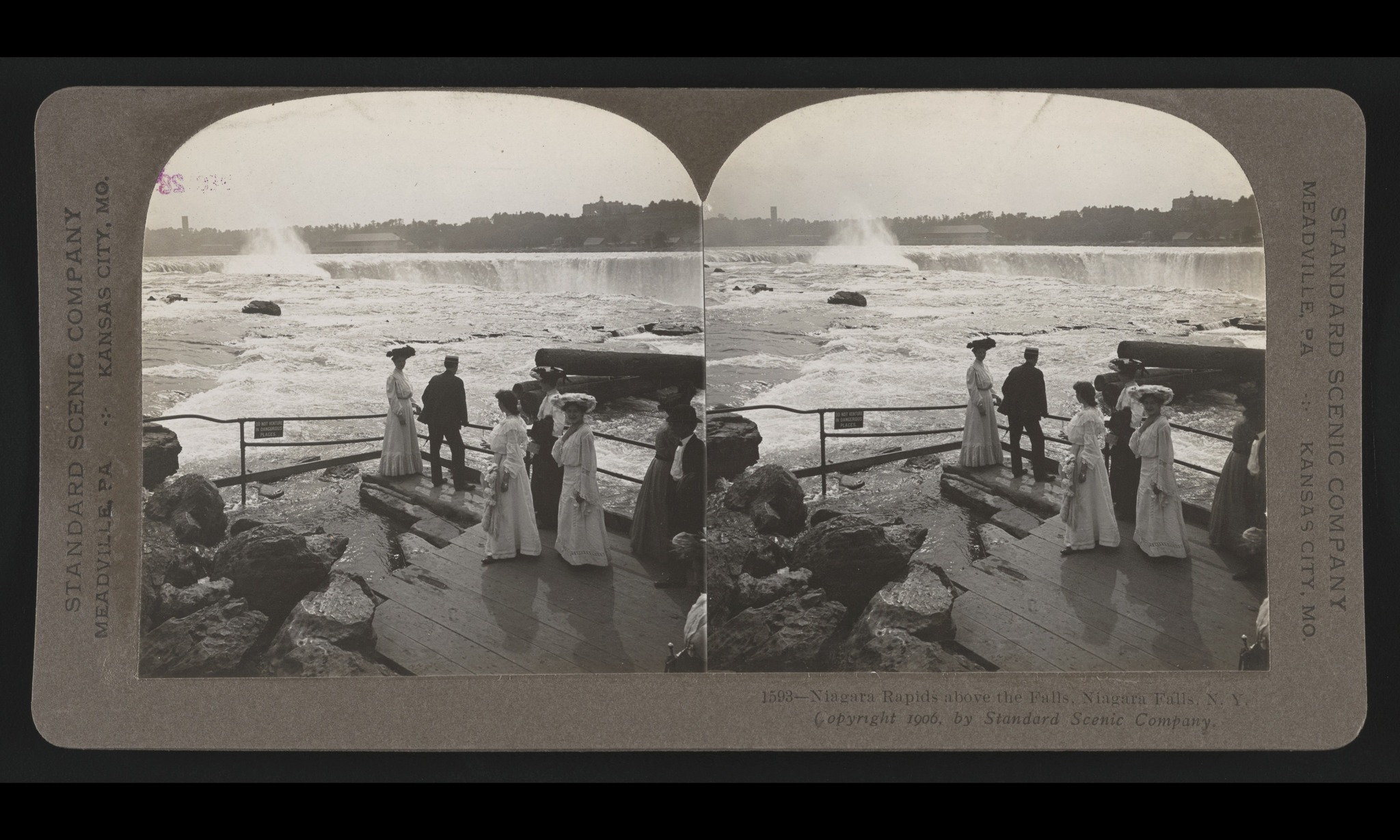

Although looking like a wedding party, these stereographed tourists at Goat Island’s Terrapin Point were outfitted in 1906 casualwear. Romantic landscape tourists of the Victorian Era interpreted nature like a landscape painting with three modes of expression: sublime, beautiful, and picturesque. All three could be found at Niagara, typically located along circuitous paths easily navigated by the tourists cloaked in styles of the time who saw nature as a thing to be contemplated, not a challenge to be conquered.

SUBLIME. Sublime scenery expressed the awesome power of an immutable and unconquerable nature represented by craggy mountains, dramatic weather, or the sudden drop of an endless sheet of water. Victorian tourists disappointed with the mile-long horizontal extent of Niagara’s two falls (more a Beautiful thing) sought the sublime by exerting much effort to find a vantage point below or even behind the falls.

BEAUTIFUL. Beautiful scenery was calming, an Edenic portrayal of rounded hills and fertile plains like the view of the Niagara Peninsula from Queenston Heights accentuated by a walk up the spiral staircase to the top of Brock’s Monument.

PICTURESQUE. English artist and writer William Gilpin added the Picturesque to Edmund Burke’s binary and contrasting Sublime and Beautiful. Picturesque scenery was more intimate, irregular, untamed and frequently paired with ruins, architectural follies, or other works of humans that could be interpreted as ancient. Victorian tourists thought Three Sisters Islands to be delightfully picturesque, made more so by the “hermit” Frances Abbott who lived there from 1829 until he drowned in the Niagara River in 1931. The small cascade between Goat Island and Asenath Island is still known as Hermit Falls.

MASS TOURISM and MODERNISM eroded the old romantic landscape tourism aesthetic, but the Niagara attractions the Victorians saw still exist. Michael Hirsch is outfitted for a boat trip to the base of the falls inaugurated by the first Maid of the Mist steamboat in 1846.

A stiff wind blows down the gorge as we ride the Canadian Hornblower Niagara to the base of the falls.

The American Falls, a side gorge waterfall carrying only 10% of the water going over Niagara Falls, from the deck of the Hornblower Niagara.

Into the maelstrom at the base of Horseshoe Falls.

Some kind of insanity compels us to ride a boat close enough to North America’s largest waterfall to see only the white mist it stirs up.

Christine turns away from the awful sublimity of Niagara.

Ron L. soaked to satisfaction of having done Niagara.

The Society of Commercial Archeology conquers the unconquerable Niagara.

Rainbow Garden and Oakes Garden Theatre designed spaces at the gateway to Queen Victoria Park include an English landscaped garden, picturesque pond, and sweeping greensward all within a block of Clifton Hill’s House of Frankenstein.

When the Clifton House burned to the ground in 1935, gold mining millionaire Harry Oakes bought the lot to be converted into the Oakes Garden Theatre. This was the first step in a landscaped garden gateway designed for the space between Queen Victoria Park and the tourist approach points from the United States via the Honeymoon Bridge, from the General Brock Hotel, and the Tower Inn Terminal for tourists taking the Niagara Falls, St. Catharines & Toronto boats and electric interurbans from Toronto. The Honeymoon Bridge was destroyed by a 1938 ice jam, and the interurban station was demolished to make way for its Rainbow Bridge replacement that opened with the Rainbow Garden in 1941.

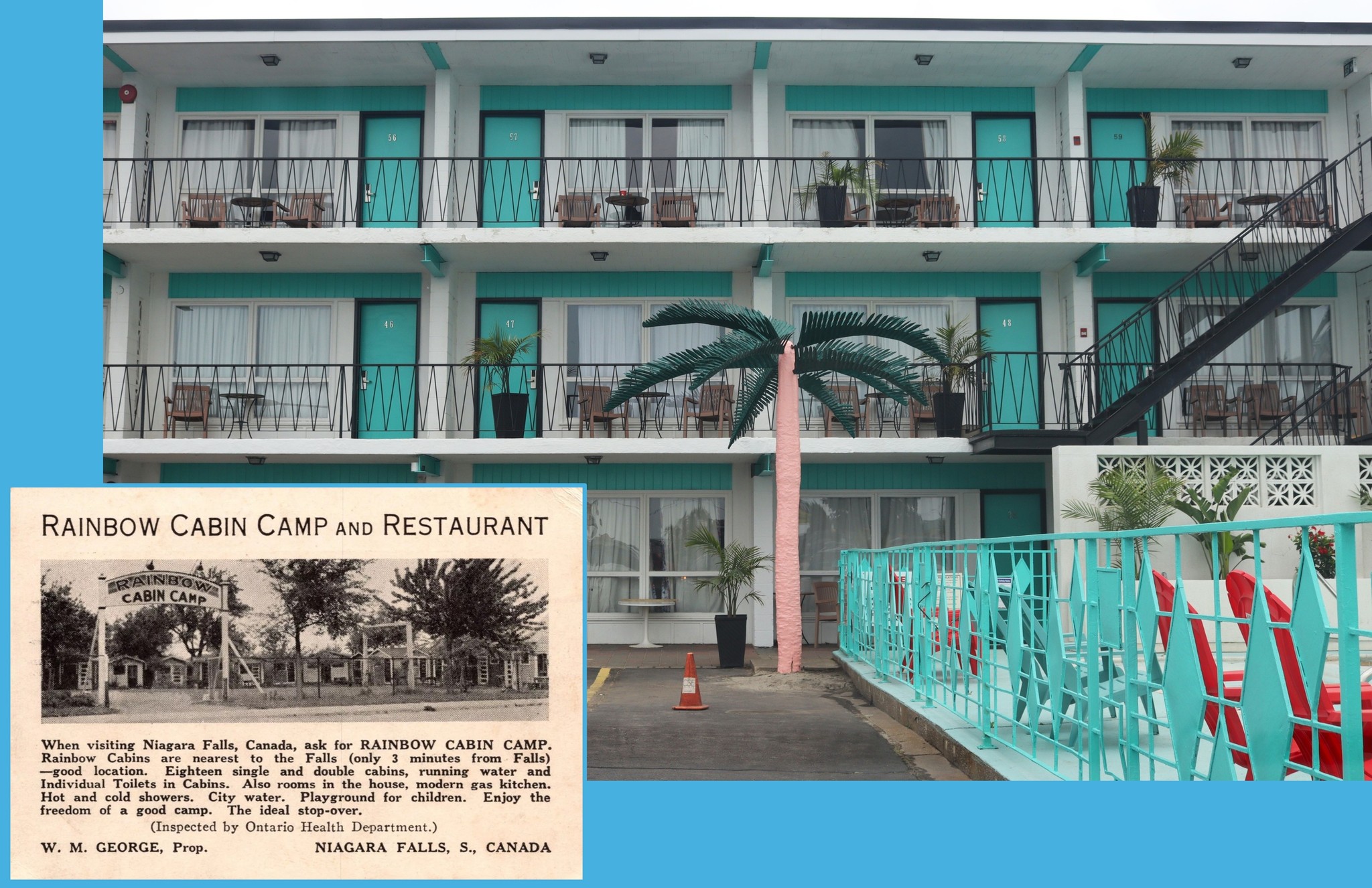

Following the premier of Marylin Monroe’s 1953 “Niagara,” Niagara Falls had its busy tourist season ever, many clamoring to stay at the Rainbow Cabins featured in the movie. Alas, the cabins were only props built at the Inspiration Point pavilion in Queen Victoria Park. The stone pavilion, constructed in 1907, was razed in the 1990s, but its fraternal twin survives at nearby Ramblers Rest.

There was a Rainbow Cabin Camp at Niagara Falls when “Niagara” was being filmed, but not the ones used in the movie. How many Marilyn Monroe-loving tourists were mistakenly drawn to this cabin court on Murray Hill in Falls View? It was rebuilt as the midcentury Modern Rainbow Motel sporting a decidedly Wildwood vibe right down to its poolside palm tree.

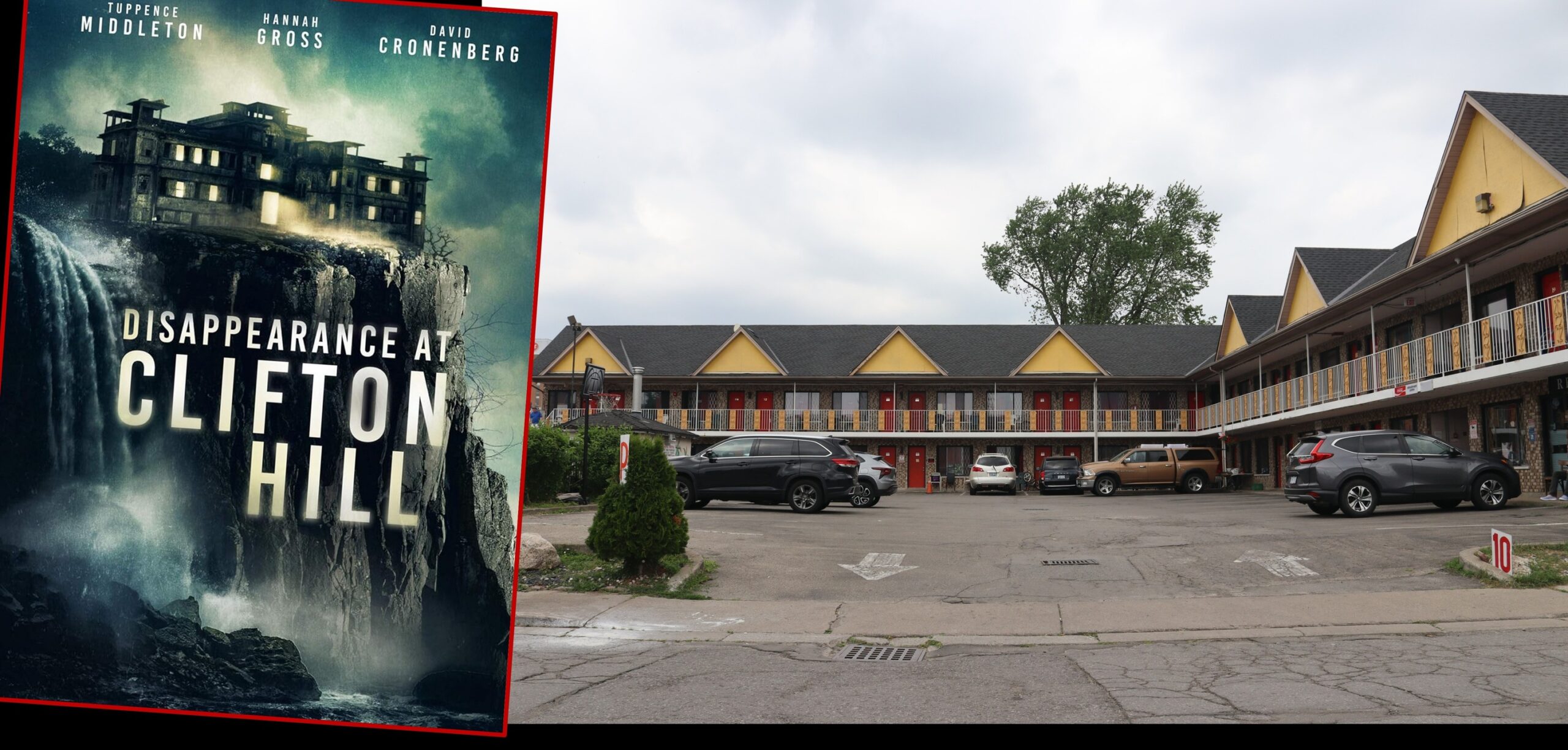

Another Niagara movie motel stands along Ellen Avenue on Clifton Hill. The Oyo Motel was the Rainbow Inn in the Canadian thriller, “Disappearance on Clifton Hill.”

The SCA rides a WE-GO articulated bus out to the Lundy’s Lane Motel Strip.

Queen Elizabeth Way, opened in 1939, carried Niagara-bound tourists directly to Lundy’s Lane where dozens of motels were built in the postwar period, including the A-1 Motel, well-maintained and little changed since 1949.

Appreciating the postmodern retro sign at the Flying Saucer Restaurant on Lundy’s Lane in Niagara Falls, Ontario.

Lunch time at the Flying Saucer Restaurant, built by Henry Di Cienzo as a Lundy’s Lane drive-in in 1972 and expanded ten years later with the addition of a dining room pod.

High winds killed our ride on the 1916 Whirlpool Aero Car over Niagara River circles in a counterclockwise direction having partially excavated the old St. Davids Gorge where the river flowed before the last glacial advance filled it with drift.

The Floral Clock, a Niagara Falls photo favorite, was built at the Sir Adam Beck hydropower plant in 1950.

Whatever your fear -heights, tight spaces, exercise, death- Brock’s Monument will bring it out. We spiraled up the same 235 steps every tourist tread since 1856 to reach the top of the tallest military monument on the British Empire. General Isaac Brock was killed in the Battle of Queenston Heights when the Americans invaded British Canada during the War of 1812. He’s buried at the base of the column.

Touring Clifton Hill with Peter Glaser. Starting as a strangers path between the Michigan Central Railroad station and Queen Victoria Park, Clifton Hill attracted auto camps and cabin courts before World War II that became large motels after World War II. Wax museums, and amusements made Clifton Hill a midway by the turn of the 21st century.

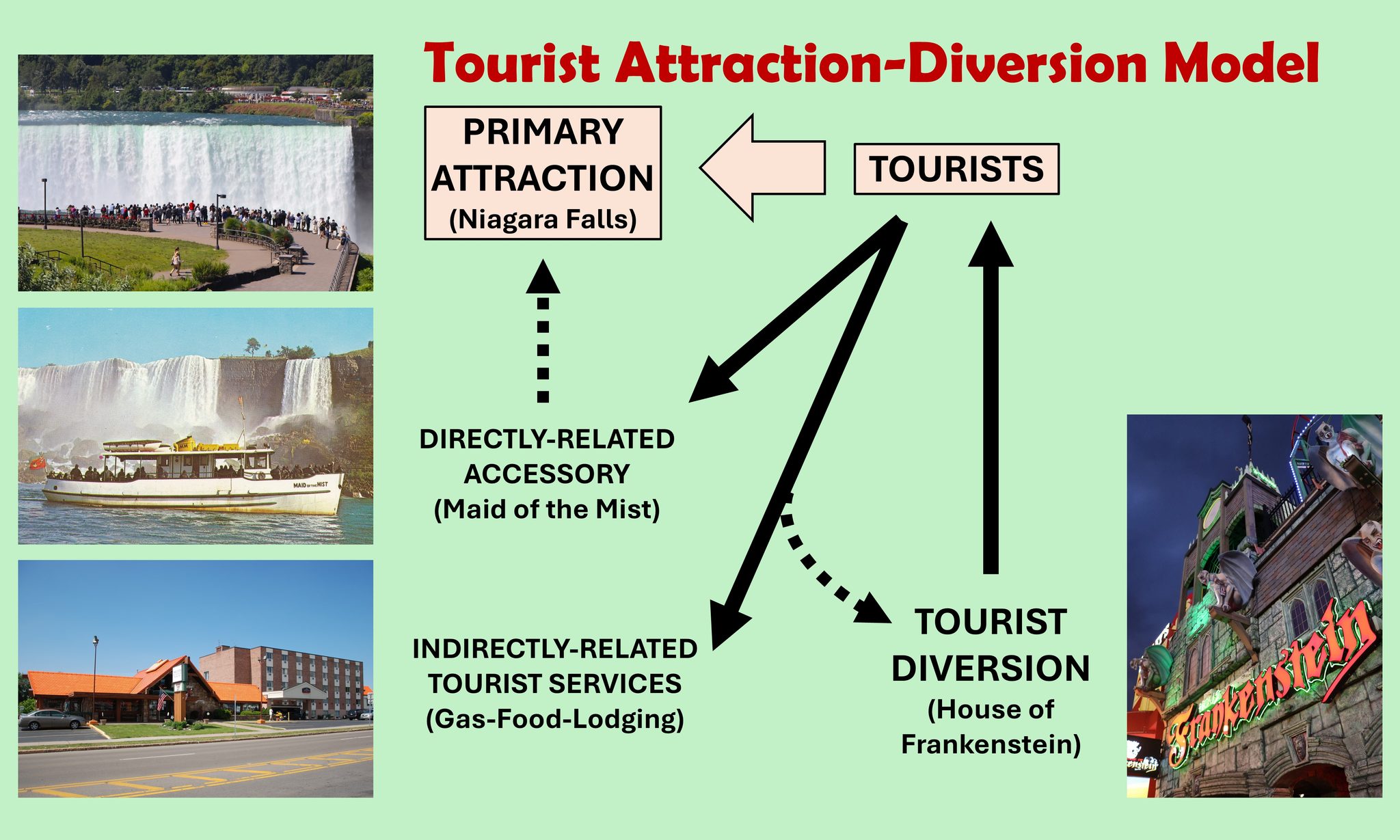

How the amusements on Clifton Hill relate to Niagara Falls: tourists drawn to the spectacle of Niagara support accessory attractions and tourist services while diversions are drawn to the agglomeration of tourists seducing them with their own kind of spectacle.

Clifton Hill Crazy. Despite the amusement detail that includes the Sky Wheel, a flaming volcano at Dinosaur Adventure Golf, and Ripley’s Believe It or Not, the entire south side of Clifton Hill Street is owned by the one firm, the Harry Oakes Company that bought the Samuel Zimmerman Estate in 1928.

Ripley’s Believe It or Not arrived on Clifton Hill in 1963 and was remodeled into the tilted tower in 2004.

Thomas Barnett opened his Niagara Falls Museum on the Canadian Front in 1827. His collection was an odd assortment of stuffed animals, Indian artifacts, and mummies (one who turned out to be Ramses I). Clifton Hill is still a place of wild incongruities where a piece of the Berlin Wall stands a short walk away from the Three Stooges.

What do you think, Tyrion?