DR. PATRICK’S

NIAGARA RECAP

(Part 2: Buffalo & the American Side of Niagara Falls)

By Kevin Patrick — with Gary S. Blatt

All photos by the author.

Kevin Patrick leads the Society for Commercial Archeology’s shuffle off to BUFFALO & the AMERICAN SIDE of NIAGARA FALLS.

SCA on the road again; on to Buffalo to see the Swan Street Diner, a 1937 Sterling made by the J. B. Judkins Company of Merrimac, Massachusetts, that operated as the Newark Diner in Newark, N.Y. until being restored and opened in Larkinville in 2017.

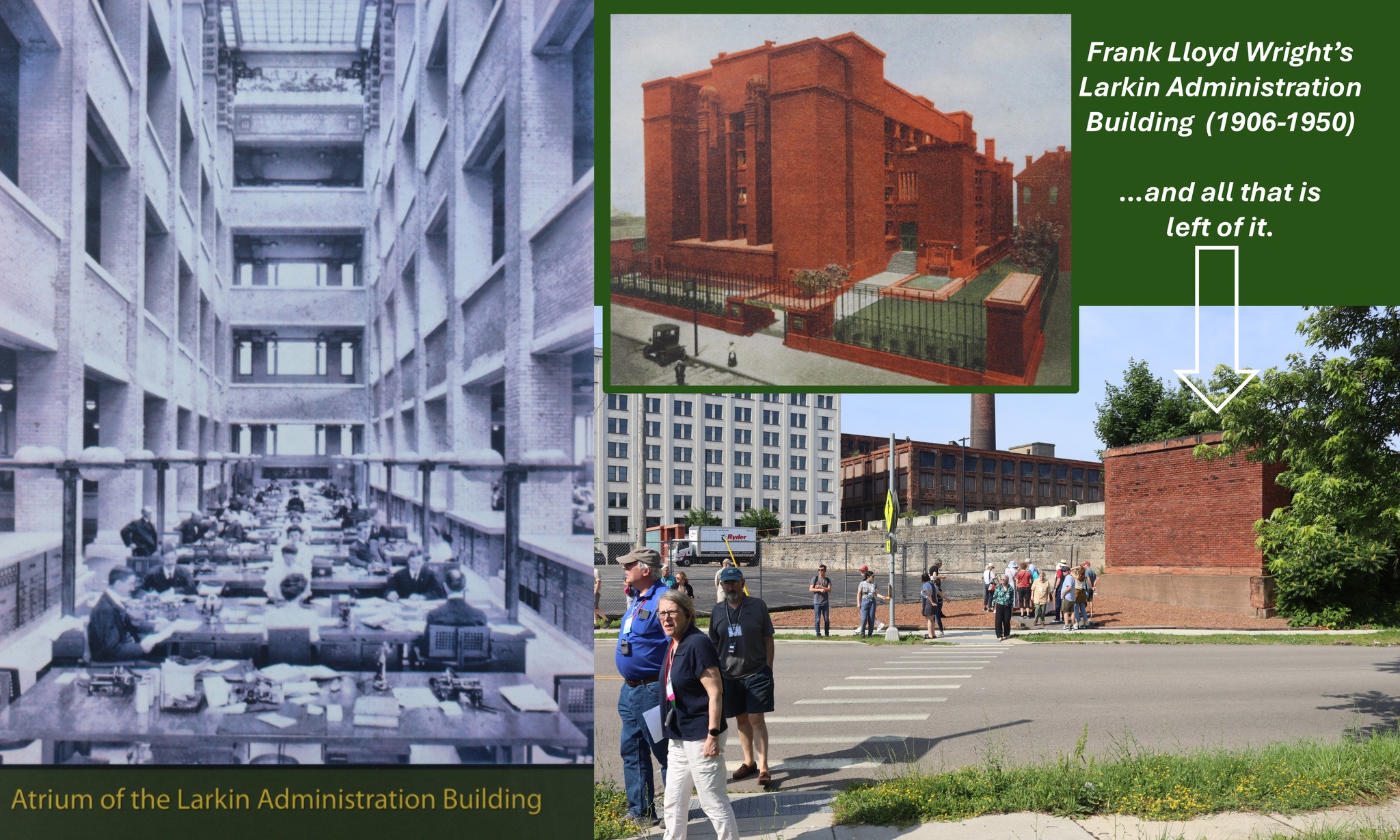

Buffalo’s Larkinville complex of industrial buildings and warehouses was built by the Larkin Soap Company beginning in 1875. Larkin expanded into a catalog mail-order company offering over 900 household products. Frank Lloyd Wright completed Larkin’s Administration Building in 1904. Weakened by the Great Depression, the Larkin Company was broken up. Wright’s abandoned Administration Building was taken over by the city for back taxes and sold to the Western Trading Company who demolished it in 1950. All that remains are two brick corner piers that anchored a fence bordering the site.

The Buffalo Transportation Pierce Arrow Museum highlights Buffalo’s role as an early auto manufacturing city hosting long-gone brands like Buffalo Electric Vehicle, Thomas, and the handcrafted, luxury car, Pierce Arrow. From 1901 until the Depression shut the company down in 1938, Pierce Arrows were built at the company’s Elmwood Avenue plant on Buffalo’s Northside. Among the antique cars, Greg and Beth make friends with a giant anthropomorphic hot dog..

The Pierce Arrow Museum’s architectural centerpiece is a Frank Lloyd Wright designed gas station the museum built from original plans in 2014. The Larkin Company commissioned Wright to design a gas station for the Buffalo corner of Michigan Avenue and Cherry Street that was never built (largely due to it being twice as expensive to construct as the average gas station). Tanks in the station’s copper roof contained the gasoline designed to be gravity fed into automobiles.

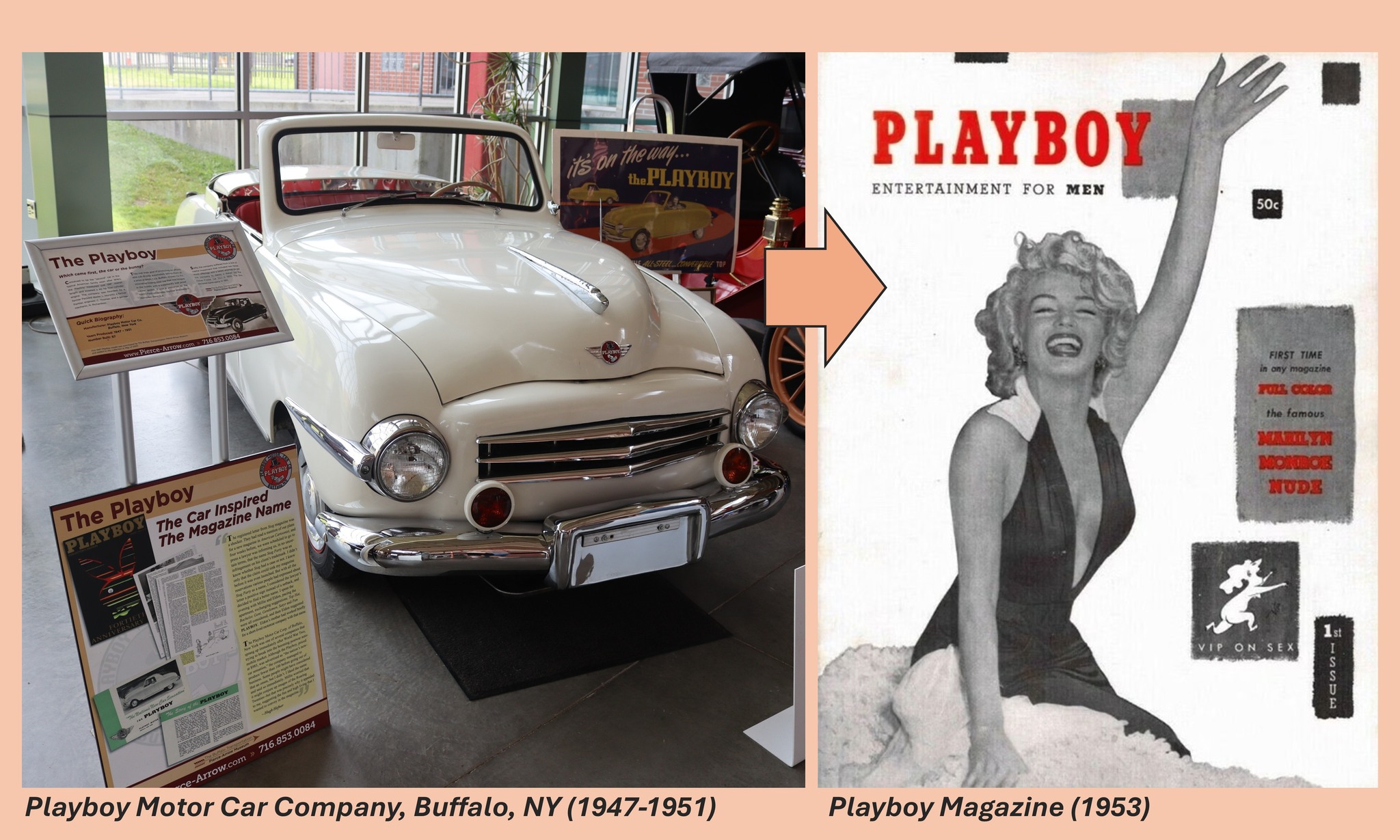

The Playboy Motor Car Company was a short-lived Buffalo manufacturer selling “second cars” to postwar families from 1947 to 1951. Two years after Playboy went bankrupt, Chicago magazine writer Hugh Hefner was trying to conjure a name for his new magazine. His partner Eldon Sellers suggested the name of the Buffalo car manufacturer that had employed his mother. .

Among Buffalo’s architectural treasures is Louis Sullivan’s Guarantee/Prudential Building completed in 1896 and covered from base to capital in red terra cotta tiles laced with Sullivans detailed decorative graphics.

With its iconic Streamline Moderne profile, Buffalo’s 1941 William Arrasmith Greyhound Bus Station survives in the Main Street Theater District as the Alleyway Theatre.

Large 360-degree cyclorama paintings -like ‘The Battle of Gettysburg’ painted by Paul Philippoteaux in 1883- were a popular form of non-motion picture entertainment in the post-Civil War era. The round building constructed to house the Buffalo Cyclorama in 1888 survives as an office building at Pearl and Edwards streets. ‘Jerusalem on the Day of Crucifixion’ was displayed here followed by the ‘Battle of Missionary Ridge,’ which was also shown at Buffalo’s 1901 Pan-American Exposition.

BUFFALO’S MAIN STREET AUTO ROW. Between 1900 and World War II, every city in America developed an automobile row along one of the main streets radiating from downtown. Typically proximate to the upscale neighborhoods that housed their market base, auto rows contained gas stations, auto parts plants and stores, tire and battery dealerships, service and storage garages, and auto showrooms, especially for luxury marques. Buffalo’s prewar automobile row was on Main Street northward from downtown where a John Graham designed Ford assembly was built in 1915 followed by Louis Kahn’s Packard showroom and garage. G. Martin Wolfe designed Charles Monroe’s Marmon and Velie showroom in 1920 that operated as a Ford sales and service garage between 1931 and 1936. Pierce Arrow’s Art Deco showroom was built at Main Street and Jewett Parkway in 1926.

Pierce Arrow’s Main Street showroom was only two blocks away from Larkin Company executive Darwin Martin’s Parkside house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1906. In addition to the Larkin Administration Building, Frank Lloyd Wright designed Buffalo houses for three different Larkin executives as well as Darwin Martin’s summer house, Greycliff, on Lake Erie.

Buffalo’s Steer Restaurant on Main Street in University Heights offering some regional classics for lunch, like Buffalo wings and beef on weck followed by sponge candy from nearby Parkside Candies.

Steer Restaurant owner Tucker Curtin brought a 1952 Mountain View to University Heights in 2017, opening it as the Lake Effect Diner. When Butko & Patrick’s “Diners of Pennsylvania” was published in 1999, the Lake Effect was operating as the China Buddha in the Philadelphia Main Line suburb of Wayne.

Buffalo architect G. Martin Wolfe designed several Main Street showrooms and two-story retail buildings including the 1927 Parkside Candies storefront and tearoom that fronted their factory in University Heights.

Parkside Candies in Buffalo’s University Heights was opened as a tearoom, ice cream counter and candy shop in 1927. Tearooms were feminine space, and Parkside Candies’ Neoclassical interior was designed to appeal to women from middle- and upper-income households in Parkside.

Allen Herschel started manufacturing hand-carved carousels in North Tonawanda, New York, in 1883. The plant on Thompson Street, now the Herschel Carrousel Museum, continued to produce carousels and other amusement rides until 1960. The museum picked up and preserved a New Jersey Pure Oil filling station cottage built in 1930.

Riding the merry-go-round at the Herschel Carrousel Museum in North Tonawanda, New York.

Herschell Carrousel also manufactured amusement park striking machines like these hand-carved bulls that tested how well the farmhands and factory workers walking the midway could kill a cow with a long-handled mallet. Drop the bull to its knees and win a prize.

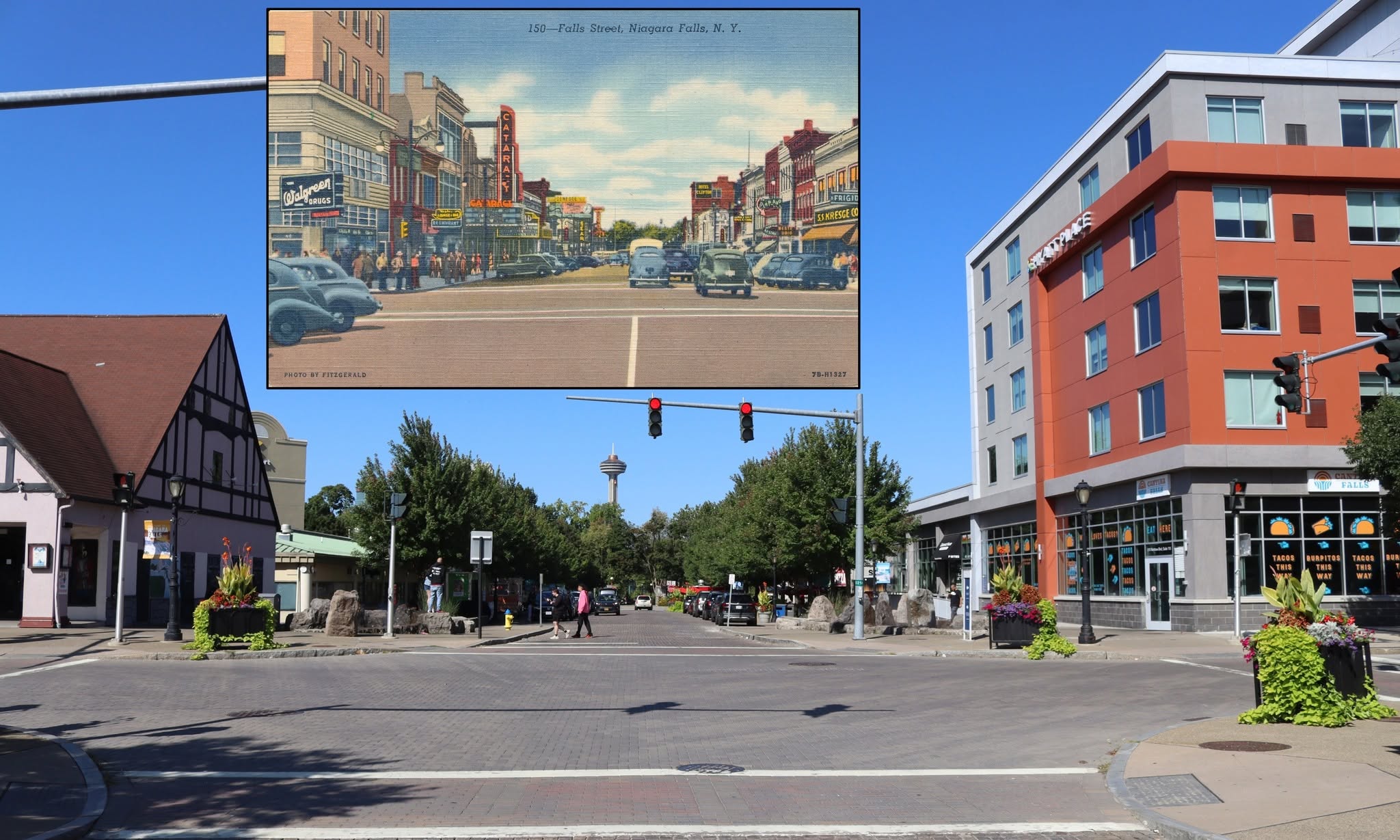

Falls Street in the tourist downtown of Niagara Falls, New York, is a sad shadow of its pre-urban renewal self that once contained a vibrant mix of hotels, theaters, banks and businesses. A 1965 urban renewal plan by acclaimed architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee turned Falls Street into a pedestrian mall anchored by an expanded Prospect Park at one end and a new convention center at the other with the Rainbow Mall in between. Expecting to be a showcase project of Modern urban planning, its fatal flaw was the wholesale obliteration of the city’s historic built environment, a tragic decision that can never be undone.

The Tudor-styled Red Coach Inn at Buffalo Avenue and Old Main Street is a Niagara Falls throw-back from 1923. The turtle head peaking around the back belongs to the Native American Center for the Living Arts that operated from 1981 until 1995 when the city took the building for back taxes. It’s been empty ever since.

The 1929 United Office Building survived the urban renewal purge that devasted Niagara Falls, New York, in the 1960s. The Mayan Revival Art Deco details, and color-graded brick façade was preserved in its conversion to the Giacomo Hotel. The 1924 Niagara Hotel across the street, once the most prestigious accommodation on the American side, awaits resurrection.

Wendt’s, a Niagara Falls dairy founded in 1929, built their Streamline Moderne plant on Buffalo Avenue in 1948, which produced milk and other dairy products until 2008.

Prophet Isaiah’s Second Coming House, is the Niagara Frontier’s most eye-popping piece of roadside folk art. Jamaican carpenter Isaiah Robertson started to transform his house on Ontario Avenue in 2014, working on his polychromatic, scripture-inspired woodwork until his death in 2020. Robertson believed Jesus’s Second Coming was eminent and would happen at Three Sisters Islands in Niagara Falls, which is why he incorporated a 300-pound boulder from the islands above Horseshoe Falls in the decorative façade of his house.

Members of the Society for Commercial Archeology, always fans of roadside folk art, take in Prophet Isaiah’s Second Coming House on Ontario Avenue in Niagara Falls, New York.

Last stop for a comprehensive sweep of any region…the cemetery. Oakwood Cemetery in Niagara Falls, New York, is the final resting place for several legendary personalities, including Annie Taylor, the first person to survive a trip of Horseshoe Falls in a barrel. She went over in 1901 (with her cat) when she was 63-years-old in an attempt achieve enough fame and fortune to fund her retirement. She died in 1921, a resident of the Niagara County poorhouse, and was buried next Carlisle Graham, who in 1886 was the first person to successful shoot the Whirlpool Rapids. A dazed but living Taylor was to shore after her 1901 stunt by Graham and Red Hill Sr., famed riverman decorated with four Niagara River life-saving medals.

Every summer day at Niagara Falls ends like it is the Fourth of July.