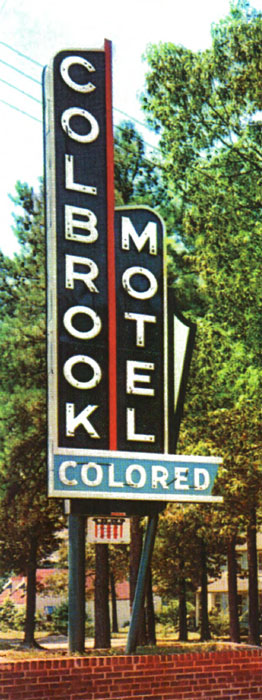

The Colbrook Motel on U.S. 1 and 301 between Richmond and Petersburg, advertised as “Virginia’s Finest Motel for Colored.” With W.E. Brooks as owner, might the first part of the motel name have been an abbreviation for “colored”? Images from the author unless noted.

Imagine that you are a proprietor of a tourist court back in the 1930s, and one day a car pulls in carrying members of a white family . . . but also a black maid. What do you do? In the March 1939 issue of Tourist Court Journal – once the major trade publication for “mom and pop” highway hostelries – the editor invited readers to share their answers to that question. The responses he got speak volumes today about what black travelers once were up against on the nation’s highways.

Of the seven court owners who responded, three would not accept black guests under any circumstances. For B.M. Bennett of the Freemont Auto Court, Las Vegas, New Mexico, this was just part of a more general policy: “We make it a strict rule never to take negro, Jap, Chinese, or any other sort of colored peoples, servants or otherwise …. Our court is for decent white people only.” O. T. Craver’s special concern at the Marshall Tourist Court in Marshall, Texas, was to keep up a reputation for tight quality control: “Since I positively do not allow negroes, the tourist is certain he is not renting a cabin recently occupied by one.” Also closed to blacks was Casa Linda Court in Gallup, New Mexico, but owner J.L. Ambrose claimed he at least always conveyed the rejection “in a nice manner” and offered to take the servant to a local hotel that did serve blacks.

Although the remaining four respondents were willing to let black servants onto their premises, three imposed conditions. At the Ocean Park Motor Court in San Francisco, according to owner C.L. Smith, “we allow colored maids to stay at our court if they wear uniforms.” Black servants could stay at the Eastham Camp in North Eastham, Massachusetts, but owner R.H. Whitford tried “to place them where they will not have to come into too close a contact with other guests” and also specified that they “not come into the restaurant while it is full of customers.” And at the Smoky Heights Resort in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, O.R. Medlin reported that he kept “one or two of our worst cot mattresses, also pillows and blankets especially for negroes and in a place to themselves.” Usually the white family will “want Mirandy to sleep in the kitchen, and her cot is placed there”; otherwise, she was sent to a storage room at the end of a garage.

Most at ease about having a black servant at his tourist court was a former Southerner, R.J. Kiker of the El Monte Court in Taos, New Mexico, who claimed a special deftness in interracial relations. Any black person coming into his court, he boasted, quickly “understands … that “he ‘done met up with white folks that knows niggers and conducts himself accordingly.” A white family traveling with a black servant, he believed, was likely to carry with them “a cot with the servant’s own bedding and [would] let him sleep in the kitchen, or else [would have him] sleep in the car.” [1]

Underlying these chilling comments was a belief, shared by editor and respondents alike, that no “respectable” tourist court would ever accommodate African Americans except as servants accompanying white motorists. Black motorists should expect to look elsewhere for lodging, but in the editor’s judgment, that posed no hardship: “In nearly every little hamlet in the South there are regular negro rooming houses, hotels and some tourist courts that cater exclusively to negroes,” which he claimed was also true in “nearly any city of five thousand or over in the United States.” [2]

On this point, the editor must have been willfully obtuse or self-bamboozled. Hoping to escape the humiliations and Jim Crow conditions of travel by train, some middle-class blacks indeed were buying cars and taking to the open road (or at least aspiring to do so) by the 1930s. [3] However, their enjoyment of long-distance travel by car was undercut by a widespread scarcity of lodging facilities available to black motorists. Writing about this problem in 1933, Alfred Edgar Smith, an early black motorist, referred to “a small cloud that stands between us and complete motor-travel freedom.” “On the trail,” Smith continued, “this cloud rarely troubles us in the mornings, but as the afternoon wears on it casts a small shadow of apprehension on our hearts and sours us a little. “Where,’ it asks us, ‘will you stay tonight?’” [4]

Interfering with Smith’s enjoyment of motoring were “the great uncertainty, the extreme difficulty of finding lodging for the night – a suitable lodging, a semi-suitable lodging, an unsuitable lodging, any lodging at all, not to mention an eatable meal.” As if in anticipation of the sanguine claims made by the editor of Tourist Court Journal about the ease of finding a room for the night, Smith spelled out the full size of the problem: “In a large city (where you have no friends) it’s hard enough, in a smaller city it’s harder, in a village or small town it’s a gigantic task, and in anything smaller it’s a matter of sheer luck. And, in spite of unfounded beliefs to the contrary, conditions are practically identical in the Mid-west, the South, the so-called Northeast, and the South-south-west.”

A 1943 study by Charles S. Johnson of “patterns of Negro segregation” in the United States backed up Smith’s main points about the nationwide scarcity of hotel accommodations for black travelers. “No Negroes are accommodated in any hotel in the South that receives white patronage,” Johnson reported, whereas in the North, “many of the hotels belong to syndicates or chains, and their policies are remarkably consistent. One or two Negroes, usually of national distinction, are accommodated on occasions at the well-known hotels [singer Marian Anderson seems to have been a frequent “beneficiary” of this policy], but in most cases some special arrangement has been made with the management. An ordinary applicant will be met with the statement that no rooms are available.” [5]

According to Johnson, a sociologist at Fisk University, only rarely were there hotels for blacks in the small towns of the South, but several could usually be found in each of the principal cities of both the South and the border states. A similar pattern prevailed elsewhere in the country – hotels “for colored” in very large cities, such as New York and Chicago, and sometimes in smaller cities with sizeable black populations (for instance, Mansfield, Ohio, had two black hotels), but virtually none in small towns and rural areas. And just how serviceable were these black hotels? In a brief note published in the NAACP’s The Crisis, editor W.E.B. DuBois claimed there were “plenty” of “decent and attractive” ones to be found in the big cities of the North, although he chastised their managers for failing to advertise them sufficiently. On the other hand, Johnson characterized the hotels operating in the cities of the South as mostly “small and questionable.” That may have been a polite understatement, if the rueful first-hand accounts of several eminent commentators can be credited. [6]

George Schuyler, editor of a black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier, attributed the “tenth-rate” character of so many black hotels to the fact that there were too few well-to-do black travelers to sustain them. [7] However, another line of argument identified segregation itself as the main cause. Some of the most lurid descriptions of black hotels in the South came from the pen of journalist Carl Rowan, who characterized many of them as “no more than ‘love pads’ operating under the eye of the police so long as the proprietor deals out the customary ‘cut’ and so long as no Negro takes a white woman in.” Rowan claimed these sleazy places, seemingly so unfit for their own commercial survival, let alone for human habitation, were mostly “owned by whites but run by Negroes” and “protected by the tariff of racial seclusion” – that is, segregation. [8]

Black writer John A. Williams agreed and asked rhetorically, “But why run [places] like that simply because Negroes, having no other place to go, have to go there?” His answer was that “segregation has made many of us lazy but has also made many of us rich without trying. No competition; therefore, take it or leave it – and you have to take it.” Reflecting on this harsh truth as he had coffee one morning in the dingy dining room of a black hotel, Williams concluded that the place “did not dismiss the code of Mississippi but enforced it to the hilt.” [9]

Two other commercial lodging options for black travelers were YM/YWCAs and tourist homes – in both cases, of course, usually ones labeled, or understood to be, “for colored.” Y’s available to blacks were likely to be found only in cities having size-able black populations, which is also where many of the far more numerous “colored” tourist homes were located. A tourist home was a private dwelling in which rooms were rented to overnight guests, but this simple definition allowed for much variation. Many tourist homes were definite commercial undertakings, made known to the public by a business name and perhaps even advertising and signage. (Johnson’s, left, was in Orangeburg, South Carolina.) Others were no more than private homes in which one or several rooms were kept vacant and available for rent to travelers.

Often the arrangements that brought travelers to these places were informal and rudimentary. According to Alfred Edgar Smith, when he was driving in an unfamiliar town and asked a black resident about the availability of lodging, too often he would get a blank stare and then a vague response along the lines of “there is no hotel for ‘us,’ there is no rooming or boarding house, but Mrs. X has a place where ‘folks stay sometimes.’ So away to Mrs. X’s across the railroad tracks.” [10]

However, itinerant entertainer Cecil Reed found that usually all he had to do was ask a black taxi driver to take him to a home where he could stay. Traveling as a professional dancer and musician, Reed took lodging in many private homes. “Many blacks in remote areas maintained extra-large homes just for this purpose,” Reed wrote in his memoirs, noting that renting rooms was for the home owner not only a way of earning extra income but also a source of excitement and contact with a wider world. “The room-and-board arrangements for black entertainers were made by each theater manager who kept lists of good homes,” Reed explained. “They had a whole network of people to call on when shows were coming to town.” Reed sometimes also found lodging on the road through the assistance of the musicians’ union to which he belonged. [11]

All courtesy African American Historical Museum & Cultural Center of Iowa

Posing as a black man and traveling with a black companion throughout the South in 1948, Ray Sprigle, reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, discovered another way in which middle-class and professional blacks solved the problem of lodging when traveling in the South. “In every Southern town there are doctors, lawyers, undertakers, insurance men, who maintain open house for Negroes who are traveling,” Sprigle found. “It’s a kind of reciprocal affair. When they [that is, the persons providing a room] travel, they are guests at the homes of friends whom they have sheltered.” No payment for lodging was ever expected, Sprigle reported, but etiquette required the visitor to press upon the hostess a contribution for her church, missionary society, or perhaps the NAACP. [12] In making a trip across the South in 1950, Carl Rowan carried references with him that allowed him occasionally to tap this system of hospitality, but he tried to keep this to a minimum, he claimed, “by leaving towns at night and riding Pullman [no easy thing for a black person to arrange in the South), or by staying on campus in cities with Negro colleges.” [13]

Doubtless the expedient most used by black motorists was arranging trip itineraries to include stays with family members and friends, or even with friends of friends. More often than not, however, this option, like the foregoing commercial ones, entailed virtually non-stop driving over great distances between cities having large concentrations of blacks. As early as 1933, Alfred Edgar Smith bewailed the fact that black motorists had necessarily become, in his word, interurbanists. “We must not tarry, cannot, to see the wonders that thrust themselves at us ’round each bend,” he noted, adding that “somehow it takes me joy out of gypsying about, when you have to be at a certain place by a certain time”; that is, by nightfall, at the next point at which lodging was assured. The imposition of this pattern, Smith observed, denied black motorists the new “world of potentiality” of motoring that white motorists enjoyed. [14] Stuck in the same “interurban” pattern that characterized train travel, automobile travel for blacks continued to be blighted by Jim Crow practices no less severe than those connected with train travel. It was also hemmed in by lodging options – remnants of a pre-automobile age –inconveniently located in dense urban areas.

New types of lodging better suited to automobile travel had begun to appear in the 1920s and were rapidly filling the roadsides in me 1930s; auto camps, cabin camps, followed quickly by tourist courts and then motels. Were any of these early roadside entities operated by and for blacks, as alleged by the editor of Tourist Court Journal? If so, the financial and licensing obstacles, as well as the relatively small cadre of black motorists available as a patronage base, must have limited their number to a mere scattered handful. But did any white-owned roadside facilities accept blacks as guests in those early days of motoring? The likelihood of that was low, too, in view of the comments by court owners published in Tourist Court Journal as well as Alfred Edgar Smith’s report about his difficulty finding lodging on the road.

Yet Smith did discover that in the Far West he was welcomed in some (but not all) tourist camps, which may be why he didn’t include the Far West in his designation, quoted earlier, of the scope of the public accommodations problem. No doubt, too, a few other white-owned courts and camps, located here and there throughout the North, were available to black motorists for idiosyncratic reasons, such as the owner’s religious, moral, or political convictions, desire to comply with a state’s public accommodation law, or, if business were bad, economic duress. [15]

But even if a few of these highway hostelries did accommodate all motorists, this couldn’t do much to alleviate the most pressing problem that black motorists faced, which was knowing which places would serve them and where those places were located. Signage would not be much help, and, in any event, the planning of trips depended on having foreknowledge of lodging options. In 1933, that enthusiastic pioneer black motorist, Alfred Edgar Smith, pointed out the obvious solution: prepare a travel guide that listed the names and locations of businesses – both black-and white-operated – that would serve black travelers. [16] By the end of the 1930s, two agencies of the federal government had issued guides listing hotels and tourist homes operated by blacks, and in 1936, the best-known commercial travel guide for blacks, the Negro Motorist Green Book, began its 30-year run of annual publication. [17] The 1940s and 1950s brought at least a half-dozen more titles of travel guides for blacks. Some were issued annually, and all purported to list both white-and black-owned places where gas, food, lodging, and other services could be obtained. [18]

Although these travel guides were always incomplete and hard to keep up-to-date and accurate, they were indispensable aids for thousands of black travelers for three decades and today provide evidence concerning the changing patterns of lodging options available to them. The 1951 edition of Negro Motorist Green Book, for instance, included only 11 highway-related lodgings (motels, cabins, motor courts), which meant that the facilities available to blacks in that year were overwhelmingly the same kinds (hotels, tourist homes, YM/YWCAs) listed 15 years earlier in the first edition of that guide. The next decade brought some forward movement, however, as was documented in a later black travel guide, The Bronze American National Travel Guide, 1961-62. Here 445 highway businesses offering lodgings can be definitely identified. The greatest number of these, 179, were located in 11 Far Western states, while another 112 were in 11 Mid-western and Plains states. Sixteen Southern and Border states accounted for 99 more of these highway businesses, but only 55 of them were tallied in 10 states in the East. Except for those located in the Southern and border states, most of these newly listed highway businesses were white-owned but accessible by black as well as white guests. [19]

An article in the June 1955 issue of Ebony had already proclaimed that “Many Motels Have Opened Doors to Negroes,” noting correctly, too, that the biggest gains were occurring in the western states. [20] Unbounded euphoria was not yet warranted, because another article in that same issue cited an unidentified survey conducted that year that found that, while 3,500 white motels were willing to accommodate dogs, only 50 stated “unhesitatingly” that they would accept black guests. However, there was also some good news: new motels that would accommodate blacks were going up throughout the United States, and especially in the South. “Motels worth more than $3 million have been built in Dixie for Negro guests,” the article claimed, adding that more were in the works. [21]

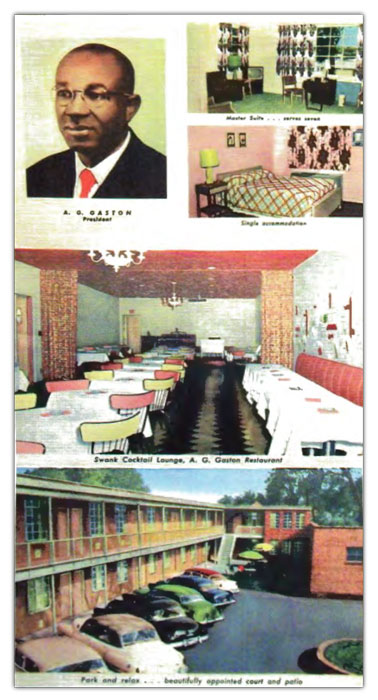

The Ebony article also noted that one of these new motels – the Booker T Motel of Humboldt, Tennessee – was “built by whites,” which hints that some white investors may have thought they had spotted a promising new market to tap. [22] But in the 1950s, surely not many were ready to put their money there, which means that most of these new motels probably were built by black entrepreneurs, and very likely, too, they had to provide their own financing. Multi-millionaire black businessman A.G. Gaston of Birmingham, Alabama, provides a good illustration. Without his entrance into the motel business and his underwriting of the entire construction costs of the Gaston Motel in 1953, there would have been no modern motel facility available to black travelers in Birmingham. [23] Motel Sepia in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, though it was much more modest in size, appointments, and cost than the luxurious Gaston Motel, was also the product of self-financed entrepreneurial effort. Returning from a vacation trip in which they and their children were frequently turned away from motels, local businessman Cecil Reed and his wife Evelyn resolved to open a motel that offered refuge to all travelers. Motel Sepia was the result of an ingenious remodeling of a small structure that Reed had just built on then U.S. 30 to house his floor-finishing and cleaning service. [24]

Photo by Cecil Reed

A black entrepreneur lacking his own financial resources was likely to face a huge obstacle, however, as was illustrated by the case of brothers A.D. “Jake” and A.S. “Big Jake” Gaither in Knoxville, Tennessee. After spending 15 months developing plans and securing a contractor for the Dogan-Gaither Motor Court, these would-be moteliers then invested at least as much time and effort looking for financing. Only after enduring 15 rejections by both white and black lending institutions approached in a nationwide search did the Gaithers finally secure a loan from the Small Business Administration. William G. Nunn, Sr., a writer for the Pittsburgh Courier, summed up the Gaithers’ experience as not an aberration but the norm. “Financing for white motels and motor courts is a non-complicated, routine business deal,” he wrote, “but where the factor of race enters into the picture, financing becomes involved and almost hopeless. Whether the approach is made to a Negro lending agency or a white institution, the answers are usually the same …‘No!’” “Negro institutions are ultra-conservative,” Nunn concluded, and “whites too often just aren’t interested.” [25]

The $100,000 Dogan-Gaither Motor Court was probably more representative of most of the new black motels than either the very modest Motel Sepia or the large, well-appointed Gaston Motel (with restaurant included), but there were some that exceeded even the latter in physical plant and luxurious offerings. The Booker Terrace (later renamed the Hampton House) included swimming pool, cocktail lounge, and night club and was the glittery home-away-from-home of many black celebrities and political figures when visiting Miami. Reaching for even more glamour and splendor was the Moulin Rouge, the first interracial casino and motor hotel in Las Vegas when it opened in 1955. [26]

The new black hostelries on the highways also included some whites-only places taken over by blacks and then upgraded. An example was the Blue Bird Tourist Court on the Lee Highway in Chattanooga, which in 1951 was renovated and reopened as the Blue Bird Motel. [27] The new owners claimed that theirs was the first motel “for colored people” in Tennessee, but, if so, the Lorraine Motel in Memphis could not have lagged very far behind. The Lorraine began as a white hotel, the Windsor, but in 1942 was bought by a black couple who renamed it the Lorraine Hotel and later, after expanding the operation and making accommodations for cars, changed the name to the Lorraine Motel. It was the only interracial motel in Memphis before passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, then gained infamy as the site of the murder of Martin Luther King in 1968. [28]

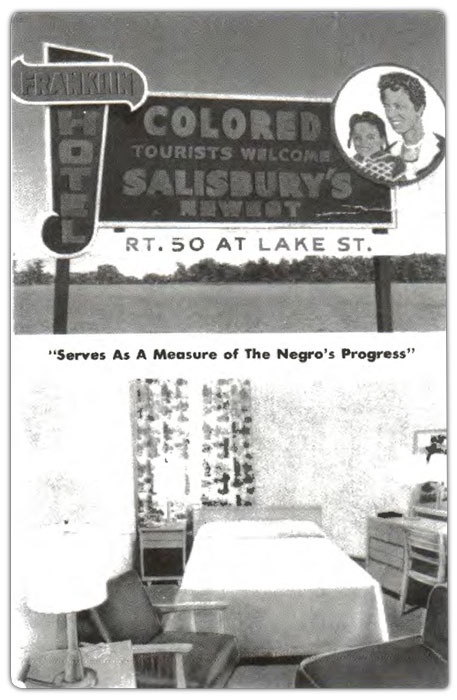

Salisbury, Maryland

The growing numbers of highway accommodations for blacks gave rise in 1952 to the Nationwide Hotel Association (NHA), whose membership was open to all businesses pledged to serve all persons equally regardless of race, color, creed, or ethnicity. In truth, most of NHA’s member businesses were black-owned hotels, tourist homes, and motels, including all those new ones heralded by the Ebony article; therefore, NHA membership figures can today give a rough indication of how fast black-owned hostelries were blossoming along highways. The 1958 NHA member ship directory listed 175 member businesses, of which only 64 were motels (the other listings were 78 hotels, 21 tourist homes, and 12 indeterminate or other types). Member businesses were located in 15 southern and border states, where the need for public accommodations for blacks was greatest, but memberships were distributed among only six states in the East, eight states in the Midwest and Great Plains, and seven states in the Far West, while 12 states had no NHA members at all. In sum, the evidence from the 1958 NHA membership directory suggests that, in the 13 years since the conclusion of World War II, including the first six years of NHA’s existence, black-owned lodging had made a definite advance but still was only a small presence on the nation’s highways. [29]

Doubtless by the mid-point of the prosperous decade of the 1960s, many more black-owned highway businesses had appeared. Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, however, abruptly eliminated the special need for hotels and motels built for the principal purpose of serving a clientele that was denied ready access to other places of lodging. Black-owned hostelries now had to compete with all other hotels and motels in a very fast-growing sector of the economy, and some pioneer black motels began to decline. Projects of so-called “urban renewal” or of intra-city freeway construction leveled urban areas in which many of the long-standing hotels, motels, and tourist homes “for colored” were located, and highway relocations put further pressure on early motels, both white and black, in the 1960s and ’70s. The closing of Motel Sepia in 1964, for instance, was the product as much of the rerouting of U.S. 30 south of Cedar Rapids as of the ending of discrimination in public accommodations.

In the absence of constant repair and upkeep, hotels and motels have relatively short lives, and since many of the early places of accommodation “for colored” were also located in urban areas that have themselves declined or been leveled, probably few of these relics of racial segregation remain. On the other hand, three of the best known – the Gaston Motel in Birmingham, the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, and the Hampton House in Miami – have in recent years been rescued from otherwise certain destruction. The Lorraine houses the National Civil Rights Museum, and the other two sites are scheduled for restoration and adaptation to various commemorative and community uses. An eminently worthwhile step now would be for state historic preservation offices to identify any other early lodging accommodations “for colored” that may still stand. Students of commercial archeology should then get busy documenting these places, as well as some of the vanished ones, from that not-so-long-ago era of Jim Crow on the highways.

About the Author: Lyell Henry is a retired Mount Mercy College political science professor and serves as historian on several projects at Lincoln Highway sites in Iowa.

Endnotes

[1] These contributions from court owners were published in a regular feature of Tourist Court Journal called “El Patio” in three successive issues in 1939, as follows: March, p. 17; April, p. 17; and May, p. 21. I am indebted to Brian Butko for informing me about these items and sending photocopies.

[2] Tourist Court Journal, April, 1939, 17. For an entertaining account of this trade magazine based in Temple, Texas, sec Anne Dingus, “Cottage Industry,” Texas Monthly, Oct. 2003, 66-72. According to Dingus, the editor was a staunch defender of the right of motel operators to exclude blacks and protested passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in an article titled “Behind the Fight for Motel Rights.” For further discussion of the realities of auto travel by blacks, see Lyell Henry, “Segregation on the Roadside,” The Iowa Griot, 4:1, Winter 2003, 4-5.

[3] Automobile travel and car ownership were pursued wit!1 special enthusiasm by black Americans, according to [W.E.B. DuBois], “Jim-Crow,” The Crisis, February 1929, 65-66; Mark S. Foster, “In the Face of ‘Jim Crow’: Prosperous Blacks and Vacations, Travel, and Outdoor Leisure, 1890-1945,” Journal of Negro History, 84:2, 1999, 140-141; Marya Annette McQuirter, “A Love Affair with Cars,” African Americans on Wheels, Spring 1998, 22-24; and George Schuyler, “Traveling Jim Crow,” The American Mercury, August 1930, 432 .

[4] Alfred Edgar Smith, “Through the Windshield,” Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, May 1933, 142-144 . A journalist, Smith wrote two columns regularly for the Chicago Defender, a black newspaper. He was also an official in the Works Progress Administration during the 1930s and later held positions in several other federal agencies. Another black journalist and frequent traveler, George Schuyler, also certified that lodging at tourist camps was almost never available to black motorists. See Schuyler, 432.

[5] Charles S. Johnson, Patterns of Negro Segregation (New York: Harper & Bros., 1943), 56, 58.

[6] [W.E.B. DuBois], “About Hotels,” The Crisis, August 1933, 94; Johnson, 56.

[7] Schuyler, 424.

[8] Carl Rowan, South of Freedom (New York: Knopf, 1954), 159.

[9] John A. Williams, This Is My Country Too (New York: New American Library, 1965), 70-71.

[10] Smith, 143.

[11] Cecil A. Reed, with, Priscilla Donovan, Fly in the Buttermilk: The Life Story of Cecil Reed (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1993), 92, 57.

[12] Ray Sprigle, “ I Was a Negro in the South for 30 Days,” published in 1948 in t!1e Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, also online at www.post-gazette. com/sprigle/default.asp. The quotations here are from Ch. 6.

[13] Rowan, 62.

[14] Smith, 142, 144.

[15] Smith, 144. For a brief discussion of several white-owned motels on U.S. 1 in Maryland that served blacks prior to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, see Eugene L. Meyer, Maryland Lost and Found (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1986), 129-131. Another such place was the Siesta Motel, located on old U.S. 40 in Reno, Nevada. I discuss the Siesta Motel in a not-yet published article (“George Washington Carver Did NOT Sleep Here!”) that addresses the difficulties that blacks once faced in traveling the route of the Lincoln Highway.

[16] Smith, 143. Smith actually was nor the first to come up with the idea of a travel guide for blacks; in fact, in his article he acknowledged that two attempts had already been made. Unfortunately, he didn’t identify them by title, saying of one only that it brought on bankruptcy for its compiler and of the other, that it was pre pared by James A. Jackson, who then departed for employment by the U .S. Department of Commerce. Although the reference to bankruptcy is puzzling, the first of these attempts probably was a guide published in 1930 by the Urban League, titled Hackley & Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers. For a detailed descript ion and analysis of this guide, see Clay Williams, “The Guide for Colored Travelers: A Reflection of the Urban League,” Journal of American and Comparative Cultures, 24: 3-4, Sept. 2001, 71-79.

[17] The government publications were Bureau of Census and Domestic Commerce, Tentative List of Hotels Operated by Negroes (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, 1937) and U.S. Travel Bureau, Directory of Negro Hotels and Guest Houses in the U.S. (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 1938).

[18] Some early titles were Travel Guide of Negro Hotels and Guest Houses, published in 1942 by a consortium of black newspapers, and “Hotels Operated by Negroes,” published in The Negro Handbook (New York: Wendell MalIiet, 1942), 31-36. Two of the best-known guides were Go Guide to Pleasant Motoring and Traveling Guide (“vacation and recreation without humiliation”). For an account of the latter, see Leslie A. Nash, Jr., “Ten Year Milestone for Travelers,” The Crisis, Oct. 1955, 458-463. The fullest guide that I’ve seen was The Bronze American National Travel Guide, 1961-62; whether it was published in other years, I don’t know. Two titles that I’ve never seen but that were advertised in Ebony magazine were Grayson’s Guide, published in Los Angeles, and one published by the Tourist Motor Club in Chicago titled TMC Guide (“travel without embarrassment”). Every June or July, Ebony also ran a “Vacation Guide” that listed hotels, motels, and resorts that would serve all travelers.

[19] Greater editorial efficiency in compiling listings might, of course, account for some (but certainly not most) of the growth in numbers of highway-related lodging facilities from the 1951 Green Guide to the 1961-62 Bronze American. For access to the se and six other black travel guides in their collection, all very scarce items, I am indebted to the African American Historical Museum and Cultural Center of Iowa in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

[20] “Many Hotels Have Opened Doors to Negroes,” Ebony, June 1955, 94.

[21] “Hotels on the Highway,” Ebony, June 1955, 93, 95, 103.

[22] Two other examples are the Hampton House in Miami (renovated and reopened by white owners in 1953) and the Moulin Rouge in Las Vegas (built by white investors in 1955). However, the Moulin Rouge remained open only for six months.

[23] Carol Jenkins and Elizabeth Gardner Hines, Black Titan (New York: Ballantine Books, 2004), 160-163. The Gaston Motel figured prominently in the Southern Christian Leadership Council’s struggles to desegregate Birmingham. Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy effectively made Room 30, the best suite of the Gaston Motel, the “war room” for directing the showdown against Sheriff Bull Connor and the resistance to civil rights in Birmingham. On May 12, I 963, a bomb blast obliterated Room 30, adjacent rooms and offices, and the motel’s facade, but, fortunately, the occupants had left the rooms 10 minutes earlier. For more on Gaston and the Gaston Motel during the civil rights years, see Jenkins and Hines, 170-230.

[24] Reed, 95-97. To build the structure, Reed had obtained small loans from three sources, but he had to provide his own financing to adapt and finish the building for use as a motel. For more on Motel Sepia, see Lyell Henry, “Serving All Travelers on the Lincoln Highway: Motel Sepia of Cedar Rapids, Iowa,” Lincoln Highway Forum, 7: 2&3, Spring/ Summer, 2000, 14-18 .

[25] William Gunn, Sr., “A Dream Come True: Dogan-Gaither Motor Court,” in N.H.A. Directory and Guide to Travel (Newark, N. J.: Nationwide Hotel Association, 1958), 20-21.

[26] For background on Hampton House, sec Jody Benjamin, “Past Glory Fades into History: The Hampton House Motel, once a Bustling Hangout That Attracted Celebrities to the Black Community in Miami, Today Lies in Ruins,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel [Miami], Feb. 18, 2001 (article available online). For Moulin Rouge, see Earnest N. Bracey, “The Moulin Rouge Mystique,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, 39:4, Winter 1996, 272-288.

[27] “Motel Is Planned Here for Colored,” Chattanooga Times, Oct. 22, 1953. The new owners announced plans to add 20 more units and a “modern colored restaurant” and to build two more motels “for colored” in the Chattanooga area. Perhaps all did not go well, however, because the Blue Bird Motel was not listed in four black travel guides from the 1950s and 1960s that I consulted. I am indebted to Martha Carver for telling me about this article and providing a photo copy.

[28] For Lorraine Motel, see Beth L. Savage, African American Historic Places (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 114), 472-473, and Nancy C. Curtis, Black Heritage Sites: The South (New York: The New Press, 1996), 26 7.

[29] N.H.A. Directory and Guide to Travel. This rare item can be found at the African American Historical Museum and Cultural Center of Iowa.

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2005, Vol. 23, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA