Medieval Dining in the Southwest

Entrance to Green Gables restaurant, 1949. All images courtesy of Dan Gosnell Jr.

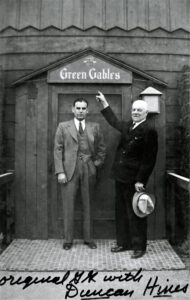

Dan Gosnell Sr. and Duncan Hines at original Green Gables, 1940.

Once upon a time, an extraordinary restaurant magically transported a generation of Phoenicians back through time and space to King Arthur’s court in medieval England. Beckoned by flaming torches along stone walls, motorists entered the compound through a gate and were led to the castle door by a knight in shining armor atop a white horse. Then, while trumpeters announced guest arrivals and Robin Hood parked their car, Lady Guinevere escorted them to their table in a dining room decorated with armor, crossbows, and pikes.

“It was like having dinner in a room out of a fairy tale,” columnist Dorothy Kilgallen wrote in Good Housekeeping magazine.

Green Gables restaurant at the southwest corner of 24th Street and Thomas Road transformed special occasions into regal events and became synonymous with milestone celebrations to many Phoenicians. “On my 21st birthday, I had my first drink with my mother at lunch at Green Gables in 1970,” Phoenix historian John Jacquemire recalls as if still savoring the Harvey Wallbanger. “After this mild initiation, I returned to Green Gables for happy hour.”

Hollywood celebrities such as Henry Fonda, Bob Hope, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Mario Lanza, and Clark Gable, who held his wedding reception there, gravitated to the upscale restaurant, which employed future star Waylon Jennings, who worked as a busboy. But before remodeling itself as a theme restaurant, Green Gables had been a nondescript eatery that struggled to attract customers. But overnight, it became the talk of Phoenix, thanks to a publicity stunt conceived by its owner, Robert Gosnell Sr.

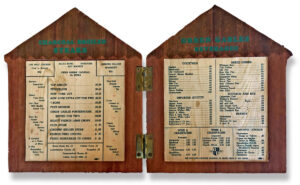

Green Gables menu, 1940.

A bank teller for Downtown’s Phoenix National Bank in the 1930s, Gosnell was disappointed with nearby eating options and decided he could do better. With a $22,000 bank loan, Gosnell purchased an 11-acre triangle formed by Thomas Road, 24th Street, and the Grand Canal on the city’s outskirts. In his spare time, using construction skills acquired from working on the nearby Horse Mesa and Coolidge dams in the 1920s, he built the original Green Gables. Sleeping on-site in a dirt-floor shack, he completed the modest wooden restaurant, which featured 30-cent martinis and $2.50 porterhouse steaks in 1939.

“You could hardly get there for the cows,” Gosnell told The Arizona Republic in 1984. “There were dairy herds on all sides.”

Perhaps because of the manure aroma, hungry diners failed to materialize. Customers were so sparse that Gosnell coaxed his aunt and her sewing-circle friends to sit in the restaurant so it would look busy, according to a 1958 Popular Mechanics article.

Gosnell sponsored the first live radio broadcast from an airplane over Phoenix to publicize his little-known business in 1940. He removed the plane’s seats and squeezed a piano into the cabin, according to the book Sky Pioneering by Ruth Reinhold. Jazz tunes played aloft by pianist Francis Beck were transmitted to KTAR studios, where future Arizona Governor John Howard Pyle provided commentary.

Unbeknownst to Gosnell, who was aloft in the airplane, halfway through the flight circling the city, a glitch abruptly ended the musical transmission. Phoenix residents who had been listening to the broadcast feared the worst. Distraught listeners jammed the phone lines to the police, airport, and KTAR’s offices, wondering if the plane had crashed.

Gosnell learned of the technical snafu when he landed and thought his marketing idea had failed. But, to his relief, the opposite occurred: The attention generated by the failed broadcast ushered in crowds to Green Gables.

There’s more! To read the rest of this article, members are invited to log in. Not a member? We invite you to join. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2023, Vol. 41, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA