Neon Pride

The Mint – 1942 Market. In 1968, longtime lesbian bar owner Charlotte Coleman opened The Mint with Peggy Forster in the shadow of the new U.S. Mint above the Safeway supermarket. Originally a steakhouse and piano bar, it evolved into a karaoke bar in 1993. If The Mint is within the boundaries of the Castro area, it is the longest continuously operated gay bar to operate with the same name. The sign design features a tiny pink “the” inside the loop of the green “M.” Photo by Al Barna.

GAY BARS WERE USUALLY HIDDEN, unmarked enclaves for only those in the know. Marginalized, much like their clientele, they were frequently found in underdeveloped or industrial sections of a town or well off the beaten path in rural areas. Often veiled behind tinted glass, with narrow entrances to allow doorkeepers to screen patrons, the bars tended to hide the goings-on within from the general public—and the police—as a matter of survival.

During the 1950s and 1960s, police routinely raided venues and harassed patrons. Authorities could arrest gay men and lesbians for impersonating the opposite gender if caught wearing the “wrong” outfit; crossdressers or transgender individuals were especially persecuted. In the late 1960s, amid the burgeoning of the modern American gay and lesbian rights movement, bars started coming out of the dark, announcing themselves with neon signs. They often became community centers, providing a safe place for marginalized members of society to socialize, organize events, sponsor sports teams, and enjoy eating together.

Many of these bars are long gone, though there are a few surviving sites. Focusing on the physical facades gives one a sense of how these bars fit into San Francisco’s social and sometimes sexual scene. These images of urban establishments are reminiscent of Eugène Atget, the French flâneur and pioneer of documentary photography, who was determined to document the architecture and street scenes of Paris before their disappearance to modernization. After Atget’s death, Berenice Abbott championed his oeuvre and took his techniques to New York City.

Similarly, Henri Leleu recognized the importance of the ephemeral in these quotidian shots of a subset of San Francisco’s marginalized social scene. Leleu, a gay man, World War II veteran, photographer, and world traveler, was active in the city’s leather scene and the Tavern Guild, the first U.S. gay business association formed in response to rising tensions between the police and homosexuals. Leleu’s images traverse the many neighborhoods that featured gay watering holes: the Waterfront, the Tenderloin, South of Market (SOMA), North Beach, Downtown, Chinatown, Haight, Polk Street, and, of course, the now world-famous Castro district.

The history of San Francisco’s gay bars is rich and fascinating, as evidenced by this small sampling of its neon signs. This article is based on a presentation by Jim Van Buskirk and Al Barna, which was inspired by the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender (GLBT) Historical Society’s online archives that offer digitized images by Henri Leleu (1907- 1996) at www.glbthistory.org/henri-leleu-bar-photographs.

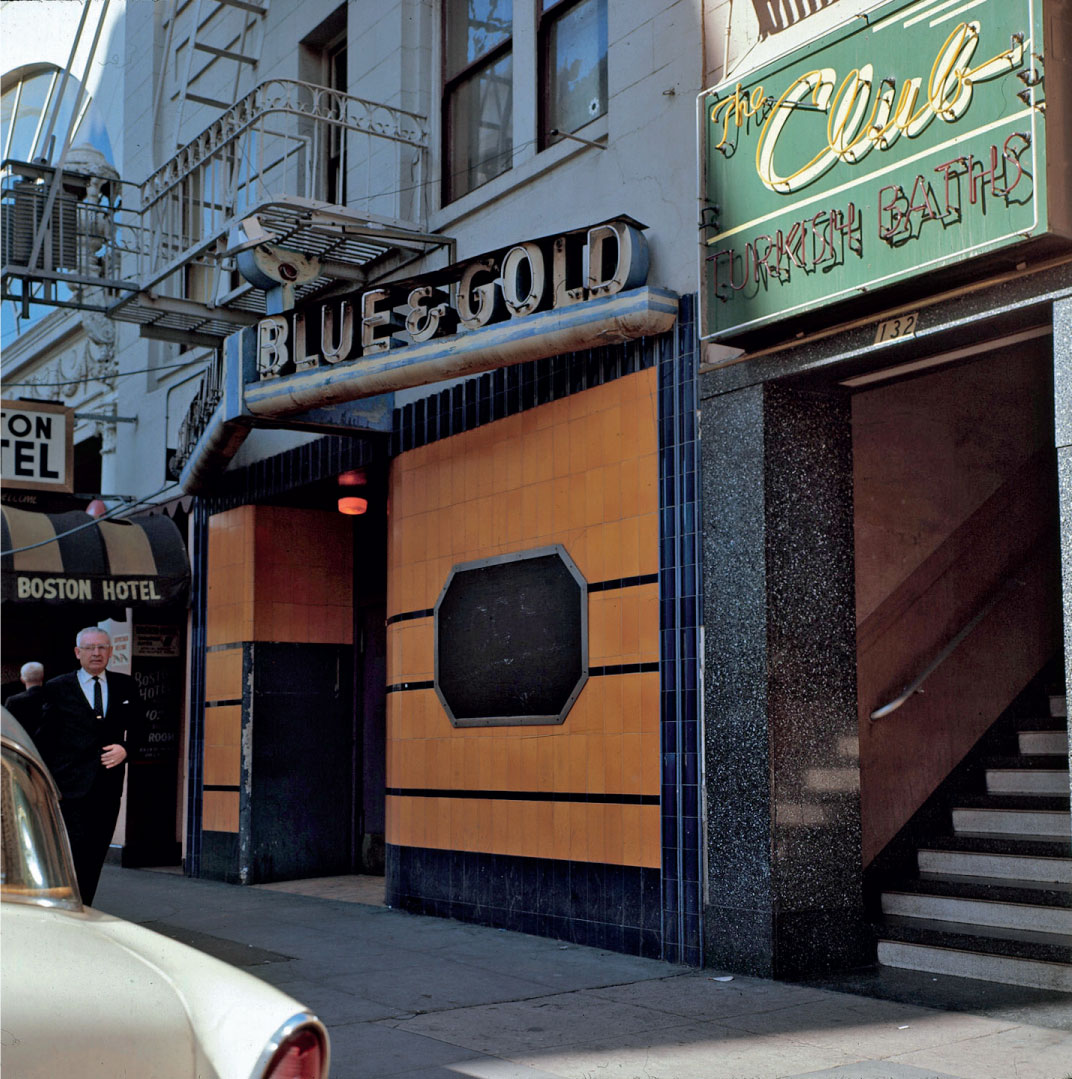

Blue & Gold – 136 Turk Street. Open from 1958–1967. From a gay travel guide: “Piano bar, some drag. Eventually developed a rough trade atmosphere. Rock performances during early 1980s quasi-gay punk.” This marquee sign with channeled raceway lettering has a sheet metal protector. Note the beautiful tilework on the building façade. Photo buy Henri Leleu.

Savoni’s Nite Cap – 699 O’Farrell at Hyde. In the late 1970s, this spot was called Lambo’s Nitecap, and when its vertical porcelain sign was repaired in the mid-to-late-1980s, a crescent moon sporting a nightcap was added to the top. Photo by Henri Leleu.

Lo-Bill’s – 704 Market. A great combination of sign typologies (fascia and projecting) with what appears to be a porcelain finish. Photo by Henri Leleu.

Twin Peaks Tavern – 401 Castro Street. This bar opened in 1935 at the corner of Castro and Market streets; Mary Ellen Cunha and Peggy Forster purchased it in 1972. When the lesbian owners opened the doors and uncovered the windows, it made history as the first gay bar in America to feature full-length, open plate glass windows that let its patrons and the public see each other. The metal box sign is shaped to represent fog rolling over San Francisco’s famous Twin Peaks. An additional neon martini glass extends over the edge of the sign. The rainbow arrows, animated by synchronized flashing lights, aim toward the commercial entrance. Photo by Al Barna.

Maud’s Study (aka Maud’s) – 937 Cole Street. Open from 1966–1989, owner Rikki Streicher claimed it as the oldest lesbian bar in the U.S. Note the double-sided projecting sign with an indicator arrow incorporated into the cabinet design and the martini glass with a painted background. Unfortunately, only a few neon signs with background paintings are left in San Francisco. Photo by Henri Leleu.

Lexington Club – 3464 19th Street. This long-gone, much-lamented lesbian watering hole, which operated from 1997–2015, is now Wildhawk. Regulars recall that the “Lex had a pretty good jukebox in the mid-2000s.” Photo by Randall Ann Homan.

Gangway – 841 Larkin Street. The Gangway has been publicly identified as a gay bar since 1961. It may have been more covertly gay for a lot longer, however, since the police first raided it for sexual activity on the premises in 1911. This photo was taken in 1984, and it closed in 2018. The tall stem of the cocktail glass creates the structure of the sign, and the original painting is so detailed, showing the icy frost on the base and cup of the glass. Left photo by Mark Carrodus, right photo by Al Barna.

Li Po Cocktail Lounge – 916 Grant Street. Though the years leading up to World War II saw growing anti-homosexual policies in the military, the outset of war meant that many gay men and lesbians still entered the armed forces. The management of the Li Po had to contend with more openly gay patrons as several nearby bars, including the popular Forbidden City and the Rickshaw, shut down during a crackdown in 1943. Li Po’s policy of forbidding some more openly queer, campy, or “swishy girls” may have prevented raids. Now more than 75 years old, it appears in the 1947 movie Lady From Shanghai. An SF Shines restoration project in 2018, for which SF Neon served as color consultants to restore the classic colors, including noviol gold letters, emerald green arrow, pure neon outlining the lantern shape, and pure argon for the word “cocktail.” Photo by Randall Ann Homan.

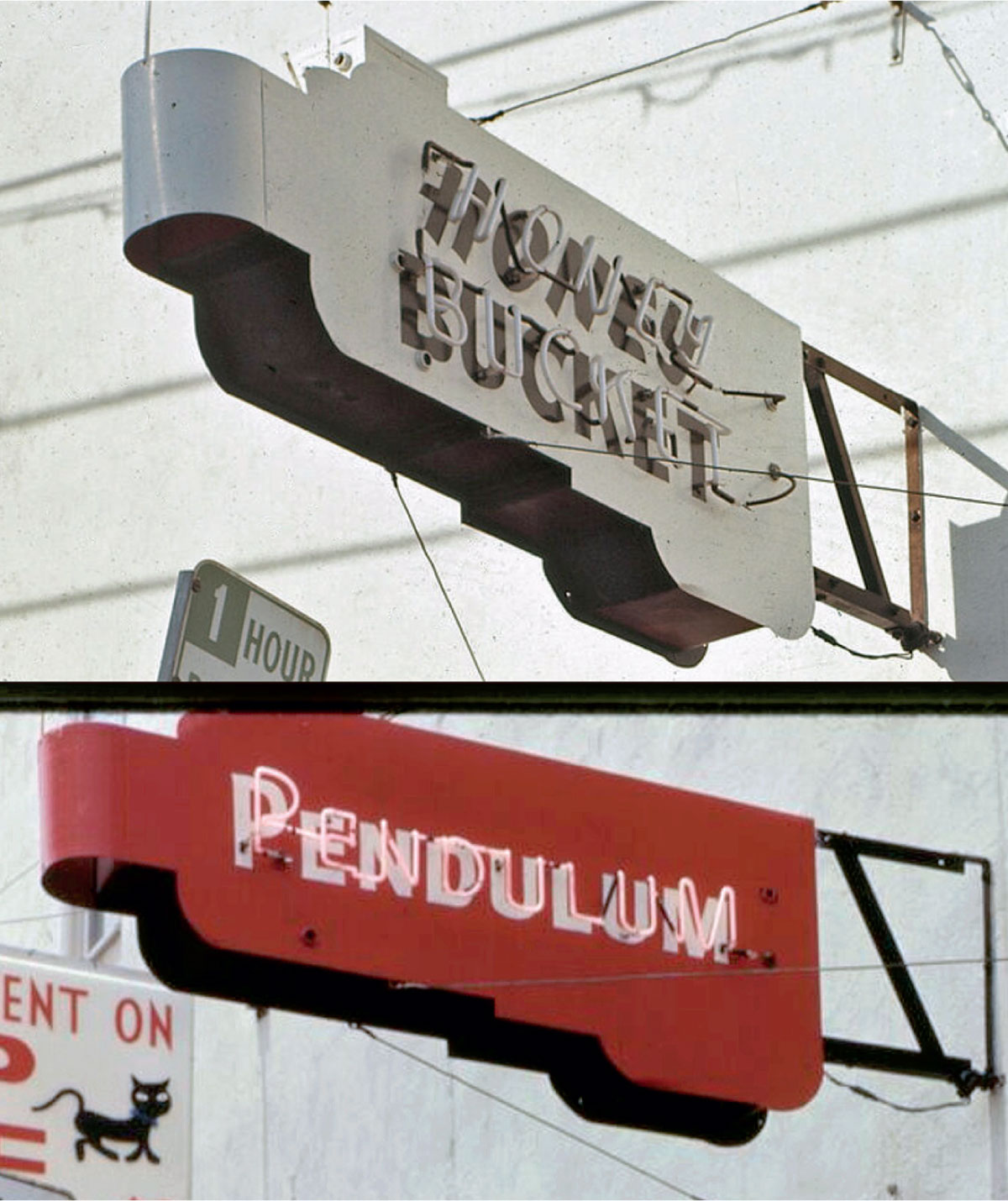

Honey Bucket – 4146 18th Street. In 1967, Mart’s Place, an old bar catering to “crusty old Scandinavians,” became I-Do-Know [I-Do-No?], the second gay bar in the Castro neighborhood, after the Missouri Mule. The bar became the Honey Bucket in 1969, and in 1971, it shed three letters to become the Pendulum, the first gay bar in the neighborhood to cater to African American gay men and their admirers. The bar closed in 2005. Note the unusual shape of the tin can; when money is an object, go minimalist! Photo by Henri Leleu.

House of Harmony – 1312 Polk Street. Notice the neon overlay of the martini glass and music notes with the script lettering and, of course, the light bulb action. Photo by Henri Leleu.

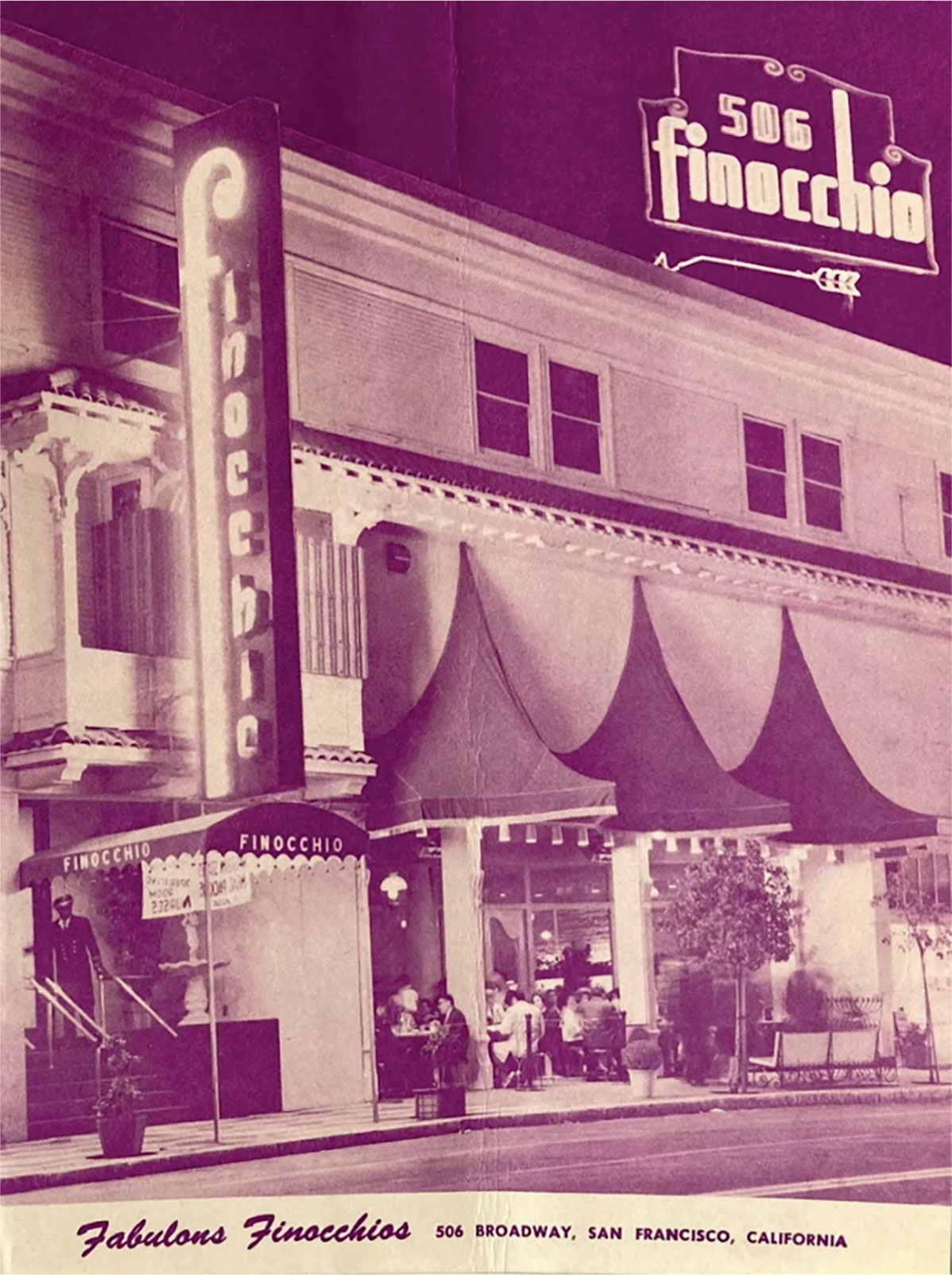

Finocchio – 406 Stockton Street. The nightclub opened June 15, 1936, above Enrico’s Cafe at 506 Broadway Street. The club was not advertised as a gay club but as a place for entertainment and fun. Both gay and straight performers worked there. In the days before gay liberation, female impersonator clubs provided semi-public social spaces for sexual minorities to congregate. It closed in November 1999, and the GLBT Historical Society now owns the blade sign. Look at that fabulous “f”! Brochure from Allen Sawyer, photo by Douglas Towne.

Jim Van Buskirk is the co-author of Gay by the Bay: A History of Queer Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area and co-editor of Love, Castro Street: Reflections of San Francisco. The founding program manager of the San Francisco Public Library’s James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center, he has served as an advisor and copresenter for Neon Speaks. Visit jimvanbuskirk.com.

Al Barna and Randall Ann Homan are a husband and- wife team who authored San Francisco Neon: Survivors and Lost Icons, Neon Icons catalog, and Saving Neon: A Best Practices Guide. They are the co-founders, producers, and hosts of the annual International Neon Speaks Festival & Symposium. Through the fiscal sponsorship of the Tenderloin Museum, they formed the not-for-profit organization San Francisco Neon to advocate for preserving the artistic legacy of historic neon signs via talks, tours, events, sign design, consultations, and books. Visit sfneon.org.

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2023, Vol. 41, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA