Neon: A Light History

By Dydia DeLyser and Paul Greenstein

San Francisco: Giant Orange Press, 2021

Softcover, 88 pages, $25

Reviewed by Douglas C. Towne

There’s a new book on neon signs that excels at, in the authors’ words, bringing “the light of the past into the present.” The cleverly titled Neon: A Light History beautifully and meticulously illuminates the evolution of this electrifying advertising medium. But that’s only the start. The text goes a step further and connects neon signs with the larger economic and societal forces that impacted them, placing them in the crux of American history.

There’s a new book on neon signs that excels at, in the authors’ words, bringing “the light of the past into the present.” The cleverly titled Neon: A Light History beautifully and meticulously illuminates the evolution of this electrifying advertising medium. But that’s only the start. The text goes a step further and connects neon signs with the larger economic and societal forces that impacted them, placing them in the crux of American history.

Concise, articulate, and illustrated with neon photography, historic and contemporary, and related vintage advertisements, you’d never guess this publication is a cleverly disguised academic gem, sans the references. If I were teaching a class on neon signs and could assign just one book, this would be the one. Its highlights are many, but perhaps most significantly, it makes a compelling case that, according to the authors, “neon signs represent so much that Americans value.”

For anyone needing a crash course, the “Neon Milestones” page opposite the inner cover is the best cheat sheet I’ve read on the topic. The complete story from the 1600s to the present appears in 19 brief sidebars denoted by eye-catching thumbnail images. Those who memorize even half of this chronological overview are sure to dazzle fellow passengers on the next SCA bus tour. The sidebars veer from the first notation about neon’s humble laboratory beginnings, “Jean Picard agitates a mercury barometer and achieves a faint glow (of static electricity) above the mercury column,” to this mid-20th century description that links neon to broad trends:

Growing cities like Las Vegas carry neon to new heights and new lows. Neon becomes linked with gambling, drinking, and illicit sex. Old signs in poor repair come to represent the failure of neighborhoods and even of society.

Perhaps the book’s most exciting revelation is the crowning a new father of neon lighting. Daniel McFarlan Moore is spotlighted as the visionary who gave the world radiant tubing. This little-known American inventor sold his patents to General Electric and continued doing electrical research. His other iconic invention is the Moore neon glim lamp, the small orange ready light in many home appliances such as coffee makers. Sadly, an electrician jealous of Moore’s accomplishments later murdered him. Even back then, neon ignited strong passions.

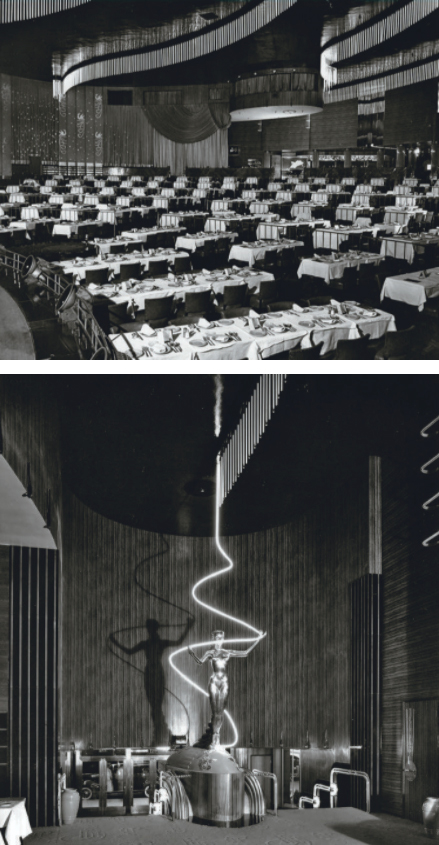

Images of Earl Carroll Theatre in Los Angeles.

French inventor Georges Claude becomes a supporting actor, whose talents lie more as a self-promoter and businessman who created the Claude Neon Lights company. Claude’s reputation takes a few hits, both artistic and political. He’s quoted in the book as initially calling neon’s red hue “objectionable” and “hardly acceptable,” but eventually sees their commercial potential. However, these are peccadilloes compared to Claude’s later collaboration with the Nazis and boastful claims that he invented neon signs.

French inventor Georges Claude becomes a supporting actor, whose talents lie more as a self-promoter and businessman who created the Claude Neon Lights company. Claude’s reputation takes a few hits, both artistic and political. He’s quoted in the book as initially calling neon’s red hue “objectionable” and “hardly acceptable,” but eventually sees their commercial potential. However, these are peccadilloes compared to Claude’s later collaboration with the Nazis and boastful claims that he invented neon signs.

These revelations led to the authors’ questioning one of the Holy Grails of American roadside history: the first stateside lighting of a neon sign at Earl C. Anthony’s Packard Motors dealership in San Francisco (or Los Angeles) in 1922 (or 1923). These new signs were allegedly revolutionary enough to “stop traffic” and necessitated extra traffic officers from the Los Angeles Police Department. However, the authors’ detailed investigations indicate that, at best, these were the frst Claude Neon Lights signs imported to the U.S. Instead, the first commercial neon-filled sign was domestically produced in Newark, New Jersey, by Moore’s coworkers for the Ingersoll Watch Company way back in 1909.

The text, interspersed between the book’s many compelling illustrations, articulates neon’s evolution and why SCA members flock to the medium like moths:

Over the past century, neon’s history evolved from a 19th- century invention to a 20th-century vision of modernity; then from a mid-century exuberance and even excess, into eclipse and near extinction, and finally to a 21st-century revival in art and nostalgia. Not a sad nostalgia, but as we will show in this book, an enchantment with distance in time and space that compels viewers to feel closer to the past, and to stories and experiences grounded in local communities.

A personal bonus is the authors’ extensive knowledge of Los Angeles, which is the focal point of much of the book. I’ve long photographed the city, so whether it’s Circus Liquors in Burbank that SCA member Kristin Leuschner surprised me with as the exclamation point on a neon tour in 2004 or The House of Spirits in Echo Park that I stumbled upon in 1991, it’s like looking through a yearbook and seeing old friends.

The cover image of a woman’s face in neon initially seemed an odd choice but turned out to foreshadow a fascinating tale about the Earl Carroll Theatre in Los Angeles. A luminous palace, the building featured a 20-foot- tall neon portrait, and its neon-drenched interior included 1,200 3-foot-long, glass-tube pendants.

It’s only conjecture, but I suspect the book’s success is due to the authors’ synergistic expertise. The wife and husband team of Dydia DeLyser and Paul Greenstein are an academic whose research interests include neon signs (where were those professors when I was in school?!) and a long- time neon artisan. Greenstein’s talents lie in the mechanics of signs, while DeLyser excels at connecting the dots across many subjects and conveys her findings in clear, engaging writing.

DeLyser and Greenstein recruited the crème de la crème of the sign world to assist them in their non-proft, labor-of-love book, of which they donate a portion of sales to the Museum of Neon Art. Another neon-powered couple, Randall Ann Homan and Al Barna of San Francisco Neon fame, designed the publication, while a host of talented artists and historians also were involved. Many are familiar to SCA readers, such as Kim Cooper, Heather David, James and Karla Murray, Thomas Rinaldi, Debra Jane Seltzer, Tod Swormstedt, and Martin Treu.

I give the book my unequivocal recommendation, only partially influenced by the authors’ enthusiastic “shout-out” to the SCA’s efforts at sign preservation. Although I can’t imagine disliking a book about commercial signs, as my bookshelf can attest, publications covering this topic have proliferated in recent years. I didn’t think there was much fresh to say about the subject, but DeLyser and Greenstein proved me wrong. Very wrong.

Douglas Towne is the editor of the SCA Journal and is proud that a fellow geographer, Dydia DeLyser, wrote such a trailblazing neon book. I wonder if she, too, heard the oft- repeated question while in college, “What the heck are you going to do with a degree in that field?”

This book review originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2021, Vol. 39, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Book Reviews