By Justin Gunther

Throughout the country, in small towns and big cities, Mount Vernon is a constant presence.

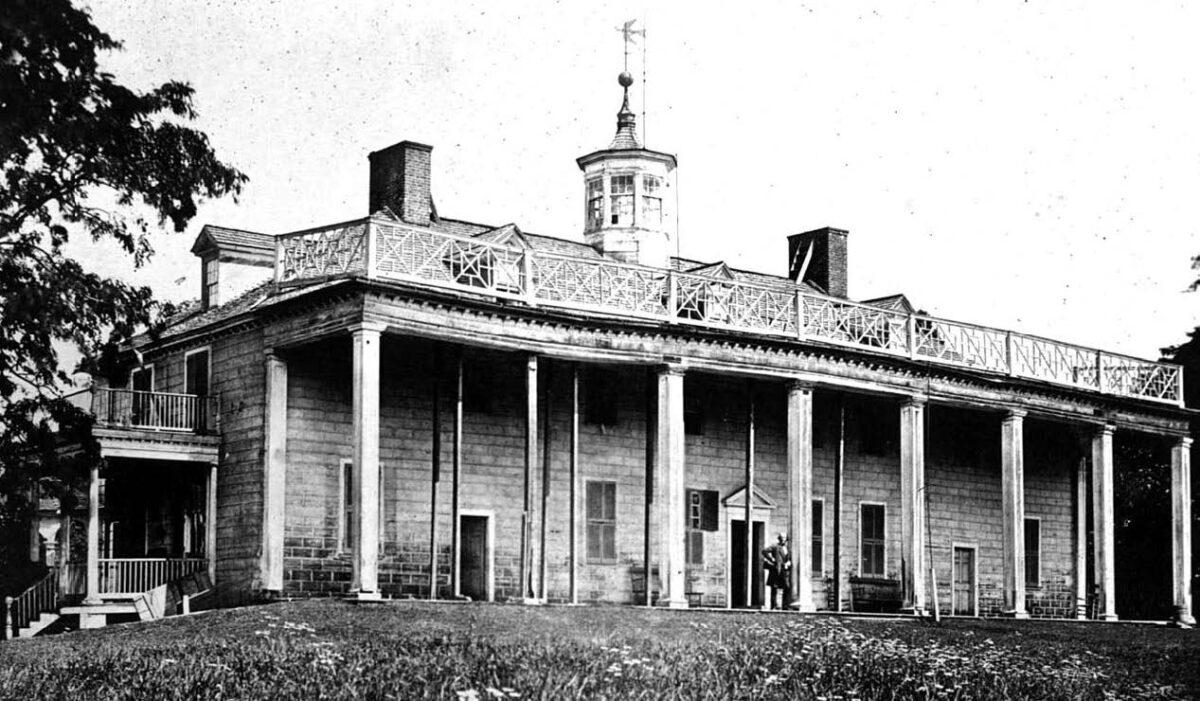

Top: Stereo card view of Mount Vernon as it appeared in the 1850s before John Augustine Washington, Jr., sold the property. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (MVLA); Above: Mount Vernon Self Storage, Richmond, Virginia. Photo by author.

The historic house’s distinctive architectural elements show up on countless buildings, both residential and commercial. Mount Vernon’s unique two-story piazza, a George Washington innovation, is the most copied component of the Mansion and has become one of the most identifiable features of American architecture. Why did Mount Vernon become such a popular design source? How did the house become a national symbol, one providing inspiration to building designers across America? This article examines those questions by tracing the popularization of Mount Vernon, beginning the analysis with George Washington, the house’s original architect.

Washington emerged from the Revolution as the central figure in the American consciousness. A man of uncompromising principles, noble carriage, and impenetrable dignity, Washington commanded an intense respect in his role as hero and president of the new republic. After his death on December 14, 1799, the mourning nation elevated Washington to an almost godlike status. The apotheosis of Washington gave the fragile American experiment a symbol of strength, and his spirit became a foundation for the nation’s identity.1

To experience his spirit firsthand, Americans and foreigners alike visited Mount Vernon. Washington’s beloved plantation, more than anywhere else, became a tangible reminder of the founding father, a materialization of his character and ideals. With their humility and grandeur, the buildings and gardens presented visitors with a reflection of Washington’s pragmatic yet sophisticated mind. The hoards of travelers eager to walk the hallowed ground were hosted by descendants of the Washington family, who continued to own Mount Vernon during the first half of the 19th century.2

Souvenir pennant, 1950s. Author’s collection.

Tourism developed as a national pastime during this period. By the 1830s, America was no longer engaged in wars or preoccupied with clearing wilderness to establish cities. Transportation vastly improved with the construction of turnpikes, invention of the steamboat, building of canals, and birth of the railroad industry. Such conditions allowed people to focus more on leisure time and travel, and tourism played an important role in the creation of an American culture. Establishing tourist sites during the country’s infancy helped shape the nation’s identity and position on the world stage.3 Mount Vernon, the home of the most revered American, was quickly adopted as a destination and became a significant component of the national image.

Similar to other 19th-century tourist attractions, Mount Vernon functioned as a sacred place. In Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture, Victor and Edith Turner suggest, “Some form of deliberate travel to a far place intimately associated with the deepest, most cherished, axiomatic values of the traveler seems to be a ‘cultural universal.’ If it is not religiously sanctioned, counseled, or encouraged, it will take other forms.”4 A country founded on religious freedom, early America embraced tourist attractions rather than specific religious sites as its destinations for pilgrimage. Places of exceptional beauty and locations associated with famous people or events appealed to people of all religious persuasions and served as points of national unity.5 Visiting Mount Vernon gave travelers the opportunity to connect with one of the greatest and noblest men in history and escape to a place that stood apart from ordinary reality. The patriotic journey to Mount Vernon was seen as a way to improve one’s character and support the nation by fostering an appreciation for the country’s founding values.

During the 1850s, many Virginia plantations suffered from the gradual elimination of profits resulting from the exhaustion of soils and changing market forces. Among them was Mount Vernon, and these conditions forced John Augustine Washington, Jr., the final family owner, to sell the estate. Understanding the importance of preserving his ancestor’s home, he refused to surrender the property to speculators. He approached both the federal government and the Commonwealth of Virginia, but politicians were preoccupied with debates over land and slavery that would eventually lead to the Civil War.6

Luckily, a group of women under the direction of Ann Pamela Cunningham banded together to raise the necessary funds. They created an organization called the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union with the mission to restore the severely decayed Mount Vernon and open its doors to the public as a museum. John Augustine Washington, Jr., agreed to sell them the estate after much negotiation, signing a contract of sale in 1858.7 With no standards to follow, the Ladies’ Association diligently undertook the challenging task of restoration. In her farewell address to fellow board members, Cunningham challenged the Ladies’ Association to “let no irreverent hand change it; no vandal hands desecrate it with the hands of—progress! Those who go to the Home in which he lived and died, wish to see in what he lived and died.”8 The saving of Mount Vernon marked the birth of America’s preservation movement and established a model for the creation of national shrines.9

Central to the success of Mount Vernon as a museum was improving access to the estate. After the Civil War, regular steamboat service from Washington, D.C., provided an alternative to traversing the notoriously bad roads of the area. Between 1892 and 1896, the Washington, Alexandria, & Mount Vernon Electric Railway was constructed creating a cheap, convenient, and extremely popular way to make the journey. As automobiles became the preferred mode of transportation, Congress authorized the construction of the Mount Vernon Memorial Highway in 1928. This parkway, linking Arlington Memorial Bridge to Mount Vernon, was completed in 1932, a symbolic year marked by the nationwide celebration of the bicentennial of Washington’s birth. Praised as “America’s Most Modern Motorway,” the road was “the ultimate blend of modern engineering, landscape architecture, historic preservation, and patriotic sentiment.”10

Coupled with the draw of George Washington, Mount Vernon’s accessibility from the capital city made the house museum one of the most visited in the world. Swarmed by tourists, Mount Vernon became known as “The Mecca of America.”11 The millions that toured the plantation took with them the image of Washington’s home, making Mount Vernon a familiar visual component within their psyche. The intense pride felt by visitors ingrained the experience as sacred in their minds.

Those unable to travel to Virginia in the 19th and early 20th centuries experienced Mount Vernon through publications, prints, postcards, and decorative arts. Engravings of Mount Vernon appeared in widely circulated periodicals like Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper; travel volumes like Nathaniel P. Willis and William H. Bartlett’s American Scenery; and books like Benson J. Lossing’s Mount Vernon and Its Associations.12 Lithographs of Mount Vernon by Currier and Ives, who described themselves as “Publishers of Cheap and Popular Pictures,” were widely purchased due to their affordability and hung in homes throughout America.13 Pictures of Mount Vernon were so common that John S. Adams wrote in his 1856 book Town and Country; or, Life at Home and Abroad, “The house I need not describe, as most persons are acquainted with its appearance, from seeing the numerous engraved representations of it.”14 Postcards became popular in the early 1900s, and their prolific circulation spread the Mount Vernon image. Tourists to Mount Vernon chronicled their visit by sending postcards of the house and grounds to friends and family who could not come along.15 Lastly, decorative arts like Seth Thomas clocks, Staffordshire plates, Whelan sterling silver spoons, and even kitschy souvenirs like pennants were adorned with the image of Mount Vernon, adding a bit of patriotic value to these objects and reminding their owners of Washington’s home.

A card from the 1931 Exposition Coloniale Internationale booklet showing the Mount Vernon replica. Author’s collection.

Expositions coupled with the Colonial Revival were also instrumental in popularizing Mount Vernon. Historians trace the beginnings of the Colonial Revival to the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Held in the city deemed sacred for its association with the Declaration of Independence, the show commemorated the nation’s 100th birthday. Even though the exposition highlighted the latest technological wonders, visitors got caught up in the celebratory spirit of the country’s founding. They were enthralled by the “Colonial Kitchen,” an allegedly accurate depiction of early American life.16 Such romanticized interpretations of the past established the basis for the Colonial Revival movement, a socially constructed ideal that looked to early America for both inspiration and answers to modern problems. As historian Mary Miley Theobald points out, “Unsettled times often encourage people to turn to the past. Americans of the late nineteenth century had only to look back one hundred years to see an era that by comparison looked idyllic: a Golden Age of American values.”17 Reviving all things colonial became an antidote to societal ills like economic depression, rampant corruption in government, and increasing European immigration that threatened the “real” America.

Colonial became the undisputed national style after the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893. Although a year late, the exposition celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America. Pavilions for the eastern states competed with one another for colonial ambience. Massachusetts reconstructed the John Hancock House, Pennsylvania replicated Independence Hall, New Jersey and Connecticut re-created rooms where Washington slept, and New York showcased Washington relics. But Virginia reproduced the ultimate symbol of colonial America— Mount Vernon. The millions that visited the exposition saw this reconstruction complete with portraits and furniture resembling the originals. With Mount Vernon as the pinnacle example, colonial was promoted as the most fashionable architectural style.18

Faithful reconstructions of Mount Vernon were later included in the exhibition buildings of the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco; the 1926 Sesquicentennial International Exposition in Philadelphia; the 1931 Exposition Coloniale Internationale de Paris; and the 1932 George Washington Bicentennial Celebration in Brooklyn, New York.19 Of particular note is the use of Mount Vernon as the American building at the Exposition Coloniale Internationale (see image at right). Clearly, Americans considered Mount Vernon a national symbol that embodied the country’s current tastes and values. Somewhat ironic though was the choice of Mount Vernon, the home of the leader of a revolution against colonial tyranny, for an exposition honoring European and American colonization. Surrounding the Mount Vernon replica were cottages featuring displays of objects from Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Samoa, all territories of America’s burgeoning empire. Particularly pleasing to the French was the inclusion of a bedroom in the Mansion interpreted as the guest room of Lafayette.20

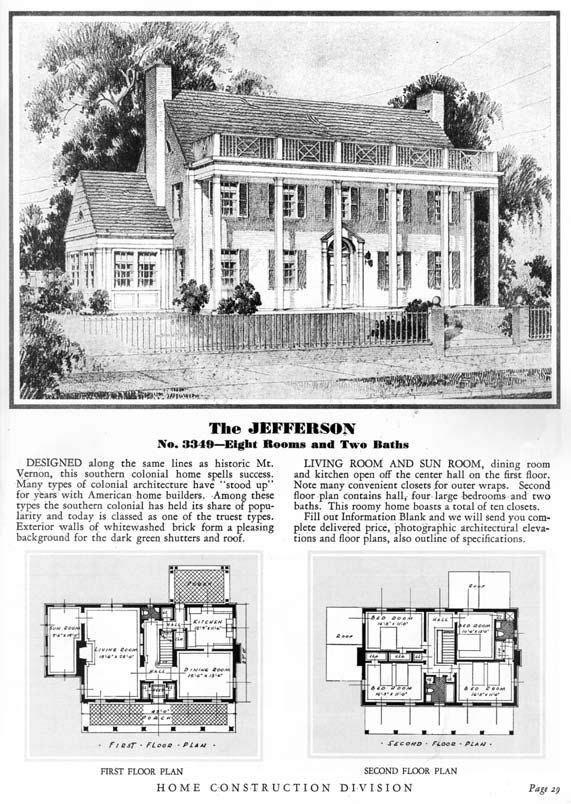

Catalog page for “The Jefferson” from Homes of Today (Chicago, 1932).

The Home Construction Division of Sears, Roebuck and Company was chosen as the contractor for erecting the Mount Vernon reproductions at both the Exposition Coloniale Internationale de Paris and the George Washington Bicentennial Celebration in Brooklyn.21 These opportunities prompted the company to offer a Mount Vernon-inspired house as part of their 1930s line of mail-order catalog homes. Called “The Jefferson,” the model capitalized on the name of another founding father, but the two-story, square-columned front porch and whitewashed brick walls with green shutters were “designed along the same lines of historic Mt. Vernon [because] this southern colonial home spells success.”22 Not as conservative as the popular bungalow models, “The Jefferson” kit had a price tag over $3,000 and provided materials and instructions to build an eight-room, two-bath house (see image at right).23

Sears was not the only company to promote suburban homes in the form of Mount Vernon. Developers across the country took advantage of Mount Vernon’s popularity and that of the Colonial Revival style. The architecture’s uncomplicated forms were simple to design and build, and Mount Vernon’s distinctive two-story piazza could be easily added to homes with a basic rectangular plan.24 A more romantic notion called “associationism” provides further explanation as to why houses were patterned on Mount Vernon. The idea that architecture shaped character led people to purchase homes that personified noble colonial virtues.25 In addition, the chasteness and restraint in form was refreshing to those raised in the Victorian era, providing an escape from the decorative abundance and ornamental fuss that surrounded them in their childhood.

The use of Mount Vernon’s motifs was not limited to residential architecture. The house’s architectural elements were adapted to lend distinction to a wide array of commercial buildings. The District of Columbia’s National Airport, now Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, is a particularly remarkable example (see image below). A project of the New Deal, National Airport replaced the highly inadequate and unsafe Washington-Hoover Airport. President Franklin Roosevelt worked with architect Howard Lovewell Cheney to create a new terminal building in keeping with the neoclassical style of the capital. The front was designed to have a colonnade of eight slender columns, reminiscent of the piazza at George Washington’s home a few miles downriver. This motif was repeated on the airfi eld side by placing columns in front of a curving glass wall. Mount Vernon’s cupola was reconstituted as an all-glass control booth centered atop the new terminal.26 Pushing the association to Washington even further was the site of the new facility, Gravelly Point. This 750-acre parcel of land on the western banks of the Potomac River was historically the location of the Alexander family’s Abingdon Plantation. In 1778, John Parke Custis, the stepson of George Washington, purchased Abingdon, and the home was later the birthplace of Washington’s beloved granddaughter Eleanor “Nelly” Parke Custis.27

Top: Washington National Airport, 1940s. Author’s collection; Above: Mount Vernon Motor Lodges, West Palm Beach, Florida, 1940s. Across from the motels was a Howard Johnson’s Restaurant. Mount Vernon Motor Lodges were also located in Jacksonville, Daytona Beach, and Miami. Author’s collection.

When completed in 1941, the National Airport’s modernist colonial shell concealed one of the period’s most technologically advanced terminals. The Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) promoted National as its model airport, complete with automated baggage systems, a control tower with electronic progress boards adapted from devices used on Wall Street, and runways designed to support the new generation of planes. Officially called the “people’s airport,” National was built entirely with public funds and was hailed as the threshold to the nation.28 To remind people of the airport’s symbolism, the CAA published a pamphlet with a rendering of the terminal hovering between the Congress building and Mount Vernon and declared, “Visitors and Washingtonians will flock to the field as to one of their favorite parks.”29

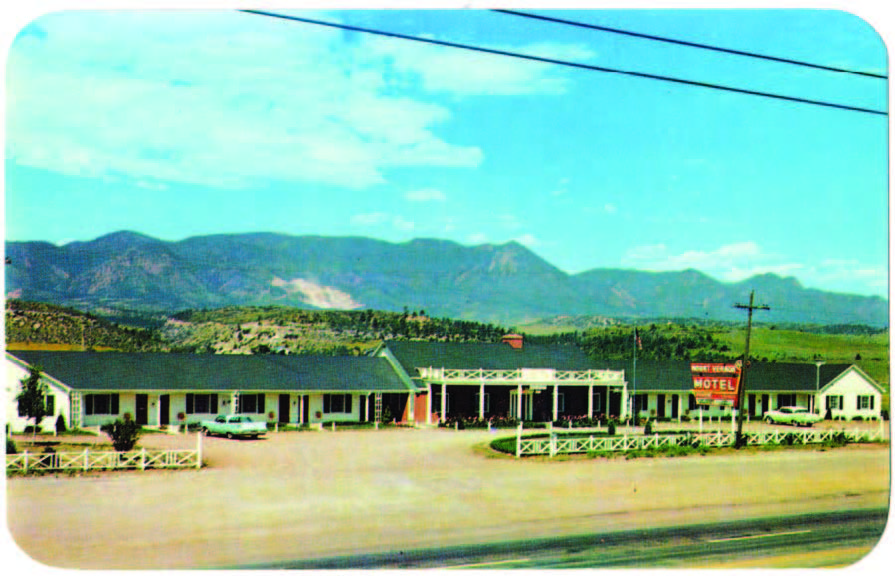

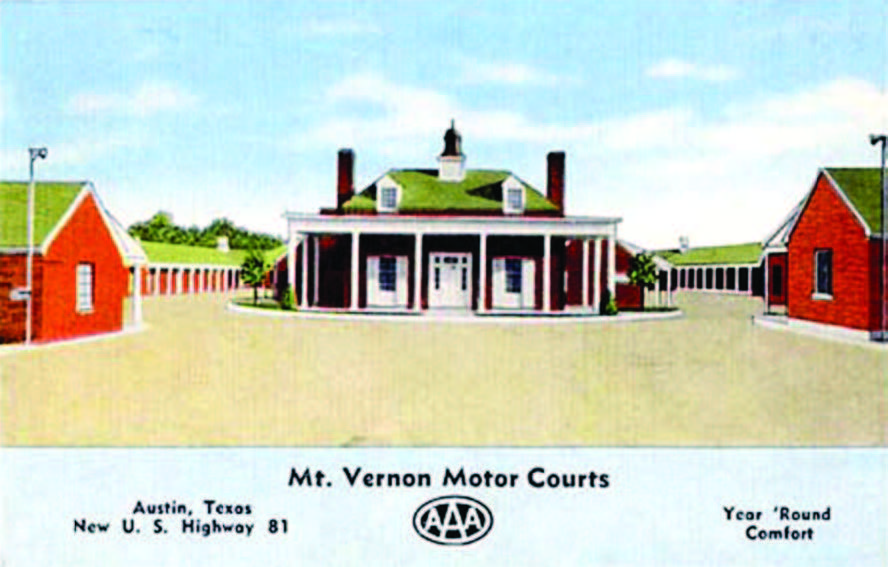

Travelers taking to the roads rather than the air encountered motels designed with Mount Vernon in mind. These motels, which often included “Mount Vernon” in their names to reinforce the connection, were built along major highways throughout the country. In Florida, for example, a chain of four Mount Vernon Motor Lodges existed along Route 1 stretching from Jacksonville to Miami (see image at left). Owners of roadside motels betted on traveler’s familiarity with Mount Vernon, hoping a columned portico and a cupola would give their establishment an edge. It is human nature to search for comfort in the unfamiliar, so after hours of exhaustive driving, motorists searched out stops that seemed pleasant, relaxing, and familiar.30 A motel resembling Mount Vernon exuded those characteristics and was a welcome sight to weary travelers (see images below).

Top: Mount Vernon Motor Lodges, West Palm Beach, Florida, 1940s. Across from the motels was a Howard Johnson’s Restaurant. Above: Mount Vernon Motor Lodges were also located in Jacksonville, Daytona Beach, and Miami. Author’s collection. Below: Mount Vernon Motel, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1950s. Author’s collection; Mt. Vernon Motor Courts, Austin, Texas, 1940s. Richard Kummerlowe.

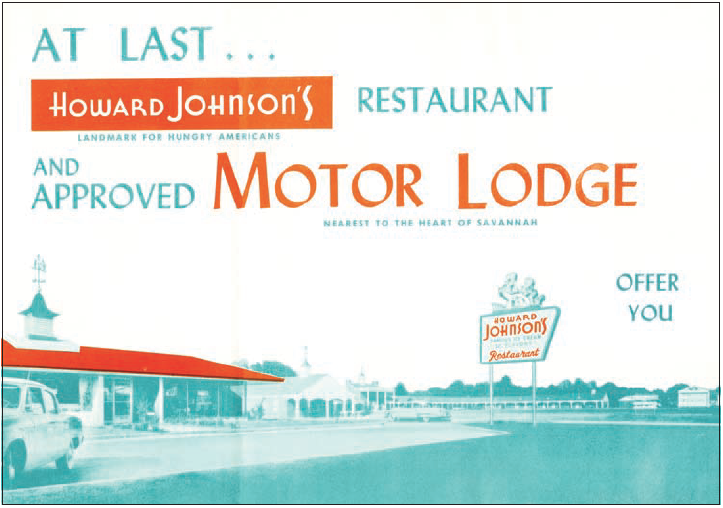

From the late 1930s to the early ’50s, savvy motel proprietors built Mount Vernon-inspired motels adjacent to Howard Johnson’s restaurants up and down the east coast. The Mount Vernon style complimented the restaurants’ formulaic, colonial design, which included white clapboards, dormers, and a cupola with a weathervane. Although not colonial, each Howard Johnson’s was topped with the company’s eyecatching, trademark orange roof. Howard Johnson’s popularity with motorists made this motif an icon of the American road, and coupling the orange roof with the columns of America’s signature home proved to be a lucrative combination.31 Noticing the success of these motels, the Howard Johnson Company entered the lodging business, franchising their first Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge in December 1953. An existing motel with Mount Vernon-esque features in Savannah, Georgia, was updated and a Howard Johnson’s restaurant built adjacent (see image page 12). This Savannah location provided Northeasterners with a convenient overnight stop as they journeyed to and from Florida.32

Other examples of Mount Vernon-inspired commercial buildings populate the American landscape. They exist in a diversity and number that are astounding. Some of these maintain loose associations to Mount Vernon while others are almost exact replicas. Besides airports and motels, there are gas stations, convenience stores, shopping malls, warehouses, funeral homes, banks, and office buildings. Examples include California Federal Bank, Los Angeles, California; Mountcastle Funeral Home, Woodbridge, Virginia (see image opposite page); Daughters of the American Revolution offices, Seattle, Washington; and Mount Vernon Self Storage, Richmond, Virginia (see image page 6). The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association maintains a listing of these buildings on their website, and welcomes suggestions for additions.33

From high style to everyday, residential to commercial, buildings across the United States feature designs fashioned on Mount Vernon. The house’s distinct elements have become significant components of the American architectural vocabulary. Both the trained and inexperienced eye can identify Mount Vernon’s influence on the built environment. Combined with the need for a national identity, the house’s popularization through tourism, print media, decorative arts, and expositions elevated Mount Vernon from a family home to an archetype of American strength and endurance. George Washington’s contributions to architecture have embedded themselves into our culture, serving as symbolic reminders of the father and foundation of our nation.

As Manager of Restoration at Mount Vernon, Justin Gunther oversees the restoration and maintenance of the mansion, outbuildings, and historic reconstructions on the Mount Vernon Estate. He serves as the estate’s principal architectural conservator, and supervises and educates the restoration team on techniques and materials for period appropriate restorations. His interest in commercial and modern architecture balances out his daily immersion in 18th-century Virginia plantation life.

Image from a brochure for the Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge in Savannah, Georgia, 1954.

Endnotes

1 Wendell Garrett, “Introduction: George Washington, Founder and Father of His Country,” in George Washington’s Mount Vernon, ed. Wendell Garrett (New York: Monacelli Press, 1998), 16-29.

2 James C. Rees, “Preservation: The Ever-Changing Frontier,” in George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 221.

3 John F. Sears, Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 3-11.

4 Victor and Edith Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978), 241.

5 Sears, 6-7.

6 Gerald W. Johnson, Mount Vernon: The Story of a Shrine (New York: Random House, 1953; Mount Vernon, 1991), 19-21.

7 Ibid.

8 Anne Pamela Cunningham to the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, June 1, 1874: published in Minutes of the Council of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, 1874, 6.

9 Norman Tyler, Historic Preservation: An Introduction to Its History, Principles, and Practice (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 33-35.

10 For a complete history of transportation to Mount Vernon and the construction of the George Washington Memorial Highway, see the pamphlet Highways in Harmony: George Washington Memorial Highway, Virginia, Maryland, Washington, D.C. (Washington, D.C.: HABS/HAER, National Park Service, 1996).

11 The original source of the term “Mecca of America” is not known. It appears to have originated in tourist guidebooks and popular magazines of the 19th century.

12 Engravings of Mount Vernon appeared in numerous issues of Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. William H. Bartlett’s well-known engraving of Mount Vernon is found in Nathaniel Parker Willis, American Scenery; or, Land, Lake, and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature (London: George Virtue, 1840). Benson J. Lossing’s engravings of Mount Vernon, which were also featured in Harper’s Weekly, can be seen in a number of his books about Mount Vernon, one being Mount Vernon and Its Associations, Historical, Biographical, and Pictorial (New York: W.A. Townsend and Company, 1859).

13 For a history of Currier and Ives see Alexandra Bonfante-Warren, Currier & Ives: Portraits of a Nation (New York: MetroBooks, 1998).

14 John Stowell Adams, Town and Country; or, Life at Home and Abroad, Without and Within Us (Boston: J. Buffum, 1856), 368.

15 Martin Willoughby gives a comprehensive history of the postcard in his book, A History of Postcards: A Pictorial Record from the Turn of the Century to the Present Day (London: Studio Editions, 1992).

16 Harvey Green, “Looking Backward to the Future: The Colonial Revival and American Culture,” in Creating a Dignifi ed Past: Museums and the Colonial Revival, ed. Geoffrey L. Rossano (Savage, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefi eld Publishers, 1991), 1-3.

17 Mary Miley Theobald, “The Colonial Revival: The Past That Never Dies,” Colonial Williamsburg: The Journal of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (Summer 2002): 82

18 A description of the Mount Vernon replica built for the Columbian Exposition can be found in Hubert Howe Bancroft, The Book of the Fair: An Historical and Descriptive Presentation of the World’s Science, Art, and Industry, as Viewed through the Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893 (Chicago: The Bancroft Company, 1895), 787-88. See also The World’s Columbian Exposition: State Buildings, Portfolio of Views (Chicago and St. Louis: National Chemigraph Company, 1893).

19 Wayne Bonnett, City of Dreams: Panama-Pacifi c International Exposition (Sausalito, Calif.: Windgate Press, 1995); Offi cial Sesqui Centennial Daily Program and Guide, Saturday, October 23, 1926 (Philadelphia: Printed by Chilton Class Journal Co., 1926); History of the George Washington Bicentennial Celebration, Volume II, Literature Series (Washington, D.C.: George Washington Bicentennial Commission, 1932).

20 An excellent summary of the Exposition Coloniale Internationale de Paris with a description of the American building can be found online. Arthur Chandler, “Empire of the Republic: The Exposition Coloniale Internationale de Paris, 1931,” http://130.212.41.61/ PEF/1931a.html/ (accessed May 5, 2006).

21 Shirley Maxwell and James C. Massey, “The Story on Sears: Houses by Rail and Mail,” Old House Journal 30, no. 4 (July/ August 2002): 50. Architectural plans used by Sears, Roebuck and Company for the Mount Vernon replica at both the Exposition Coloniale Internationale and George Washington Bicentennial were drawn by Richmond architect Charles K. Bryant and are in the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association Restoration Department collection.

22 Originally published in Homes of Today (Chicago, Ill.: Sears, Roebuck and Co., 1932), the house plans for “The Jefferson” can be found in the republication, Sears House Designs of the Thirties/ Sears, Roebuck and Co. (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 2003), 29.

23 Ibid.

24 For examples of Mount Vernoninspired Colonial Revival homes see Virginia and Lee McAlester, A Field Guide to American Houses (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000), 320-353.

25 Theobald, 83.

26 Alastair Gordon, Naked Airport: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Revolutionary Structure (New York: Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2004), 117-121.

27 Mollie Somerville, Washington Walked Here: Alexandria on the Potomac, One of America’s First “New” Towns (Washington, D.C.: Acropolis Books, 1970), 121-122.

28 Gordon, 121.

29 National Airport (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, Civil Aeronautics Administration, 1941). 3

0 Information on tourist behavior was found in Larry Kotz, Tourists: How Our Fastest Growing Industry Is Changing the World (Boston: Faber and Faber, 1996), 1-18. See also Martin Oppermann, “Tourist Destination Loyalty,” Journal of Travel Research 39, no. 1 (2000): 78-84. 31 John A. Jakle and Keith A. Sculle, Fast Food: Roadside Restaurants in the Automobile Age (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999): 73-76.

32 A chronological history of the company is available online at Howard Johnson, “History,” http://www.hojo.com/ HowardJohnson/control/brand_history/ (accessed March 1, 2006). See also Glenn Wells, “A Vanishing Roadside Icon: Howard Johnson’s,” http://www.roadsidefans.com/hojo.html/ (accessed March 1, 2006); Richard Kummerlowe, “America’s Landmark: Under the Orange Roof,” http://autoage.org/ (accessed February 15, 2006).

33 Examples of architecture inspired by Mount Vernon are collected and listed by the Mount Vernon Restoration Department and are available online at http://www.mountvernon.org/learn/pres_ arch/index.cfm/pid/624/.

Mountcastle Funeral Home, Woodbridge, Virginia. Photo by author.

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2006, Vol. 24, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA

2 Comments