By Andrew Wood

Early twentieth-century motels1 reflect an emerging Age of Mobility that promised perpetual motion through a fluid continuum of consumer experiences.

Western Motel, Bethany, Oklahoma. — Photo by author.

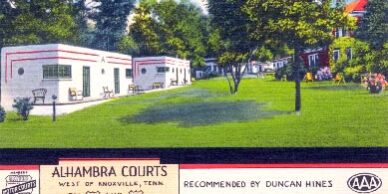

With their ersatz rustic cabins, Spanish haciendas, and native tepees, these motels responded to the increasingly homogenous and anonymous experience of interstate travel by portraying places that were particular and memorable, even if their façades offered no more than caricatures. The theming of American motels was particularly useful for motorists expanding their cultural geographies beyond the hometown. Lisa Mahar notes, “Long-distance travelers might not connect with traditional local identifiers, such as proprietors’ names, so they were replaced with broader regional symbols, or themes, that would seem more familiar.”2

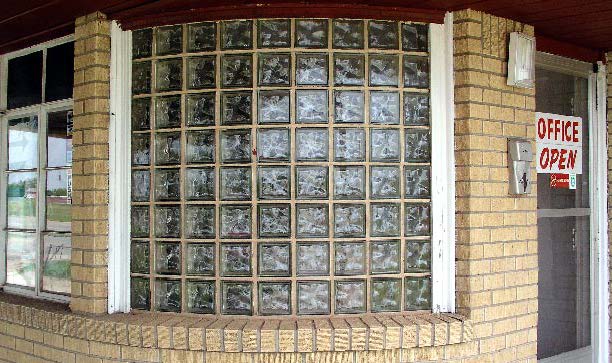

Reflecting a broader trend of American roadside design, themed motels employed a range of techniques to grab the attention of tired motorists. Vernacular architectural façades, iconic signage, and corresponding advertising materials presented an opportunity to visit the Old West, colonial America, or even a foreign land. Along with the “domestic” motif found in tiny Tudor houses and primitive stone cottages, these themes shaped much of the early roadside lodging industry. However, one theme deserves more attention than it has received in recent scholarship: the evocation of the Moderne in motel design. This essay offers an introduction to Motel Moderne by first placing the Moderne in its cultural context before describing specific motifs employed by Moderne motels.

Moderne refers to a stylized approach toward design, production, and advertisement that experienced its American zenith from the 1920s through the 1940s, manifesting itself in a range of structures from skyscrapers to staplers that abandoned traditional forms. Moderne offered “the future” as sleek, clean, and efficient — the cult of the new. An affectation of the progress narrative that animated much of the popular culture of the pre-World War II era, Moderne borrowed loosely from modern architecture, an approach toward building that celebrated the power of mass production, functional design, centralized planning, and rational decision making to enable a new and better world.3 Initially, Moderne responded to the “modern” intersection of art and political philosophy introduced in early 20th century Europe. These included the shocking display of European modern art at New York’s Armory Show (1913), the socialist sensibilities of the Weimer-era Bauhaus school (1919-1933), and the industrial aesthetics of the Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (1925). Emerging from each of these artistic and political progenitors, Moderne became an American phenomenon of modern style.

Trylon and Perisphere, 1939 New York Worldʼs Fair. — Authorʼs collection, usage courtesy Lake County, Illinois, Discovery Museum/Curt Teich Postcard.

Moderne contained two movements — decorative and streamlined — both of which reflected a fanciful vision of modern life. The Jazz Age decorative movement, often called Art Deco,4 boasted a mélange of vertical and zigzag lines, pre-Columbian elements, and stylized flora and fauna whose enthusiasm for the machine age resulted in structures such as New York’s Chrysler Building and Empire State building.5 The Depression-era streamlined movement offered a comparably unadorned simplicity whose elegance and e conomy are well illustrated by the Los Angeles Crossroads of the World Shopping Center and Greyhound bus depots built throughout the nation during the thirties.6 Eschewing Louis Sullivan’s dictum that “form ever follows function,” both the decorative and streamlined movements of Moderne offered populist reproductions of high-minded modernism whose various motifs often served no useful purpose except to be visually arresting. An example was the Trylon and Perisphere at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.7

Many United States designers and architects, particularly those who contributed to interwar fairs and expositions held in Chicago, San Francisco, and New York, repudiated the Moderne label. To them, the structures of the great fairs offered nothing less than “epideictic architecture” that would educate the public about the virtues of cleanliness, technology, and order. Indeed, the buildings and exhibits of the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair were crafted to envision a bright new world that simply awaited the global embrace of rational, “streamlined,” design.8

To those who celebrated modern architecture and allied arts, “mere” Moderne offered only a fake façade, fanciful wrapping for a gag gift. However, for many Americans, the Moderne style that transformed locomotives, theatres, diners, bus stations, advertisements, typography, and other apparently banal elements into Buck Rogers fantasies of the future offered a seemingly ubiquitous portal to the “world of tomorrow.” Such imagery may have seemed a bit silly, but it was meaningful all the same. For many people, the Moderne — despite its frequently tacky manifestations — was modern.

Motels Meet Moderne

During the 1920s and 1930s, the era when Moderne had begun its transformation from the decorative to the streamlined movement, roadside cabin camps began their parallel transformation into “modern” tourist courts. During this time, entrepreneurs who had settled on building a small number of cheap shacks, often on road-adjacent farmland without plumbing, heating, or other amenities, decided to compete with tourist homes and municipal campsites by improving their properties. The rise of the modern tourist court meant “innerspring mattresses, linoleum floors, hot and cold running water, throw rugs, and colonial-style furniture” – and indoor toilets.9 For the sake of efficiency, courtiers began to design their businesses around more organized plans, and their shacks gave way to cottages.

There’s more! To read the rest of this article, members are invited to log in. Not a member? We invite you to join. This article originally appeared in theSCA Journal, Spring 2006, Vol. 24, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA