In 1908, when brothers Edward and William Manning assumed ownership of Pacific Tea and Coffee Company at Seattle’s Pike Place Market, the marketplace was barely a year old. A lively spot, Pike Place offered Seattle-area farmers a central location to sell their fruits, vegetables, and meats directly to shoppers. To complement the farmers’ goods, Seattle retailers rented stalls in Pike Place to sell products such as groceries, mastodon tusks, flowers, and art created by local craftspeople.

Manning’s original stall, 1519 location in Seattle’s Pike Place Market, 1908. Family of Marty J. Brill.

For many Seattleites, the market was an exciting destination. Each business day, people arrived at Pike Place in horse-drawn wagons and carriages, along with a few automobiles. They often wore clothes reserved for special occasions because, for many, going to the market was a significant event. Carrying baskets in their arms, men, women, and children wandered the noisy market, greeting old friends, making new acquaintances, and gathering supplies.1

The Manning brothers’ new business occupied stall 1519 in Pike Place. To attract attention in the hustle and bustle of the market, the brothers knew they had to distinguish their business; they changed the name to Manning’s Coffee and erected four signs above the stall’s entrance and one sign on the stall’s counter that sported their new company’s name. Other signs advertised the prices of Manning’s different grades of coffee. One elaborate advertisement rose above the others, protruding outward from the top of the stall and looming over the heads of shoppers, inviting them to stop by for “Coffee Served Hot,” including small cups of coffee that cost just 2¢ and large cups priced at 4¢.

This signage attracted many customers to Manning’s Pike Place location. From this humble beginning, the company grew into a large West Coast chain with dozens of restaurants and coffee shops throughout Washington, Oregon, and California, plus specialty restaurants in Phoenix, Denver, and Salt Lake City. The company’s coffee was sold in grocery stores, with vacuum-packed cans of Manning’s coffee sitting on shelves next to cans from coffee behemoths like Folger’s and Maxwell House.

Later, the company helped transform standard operating practices for West Coast restaurants by implementing centralized food preparation that relied on prepackaged frozen foods and providing institutional feeding for organizations like hospitals and nursing homes. By the time the last Manning’s restaurant closed in 1984, the company’s reign had lasted 76 years, employed thousands of people, and posted profits in the millions.

Manning’s refurbished sign in Los Angeles’ historic Highland Park neighborhood, 2015. Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma, Stu Miller Collection.

Manning’s offers a classic example of using signage, billboards, and architecture as marketing tools to promote a successful business. As Manning’s expanded, the company’s locations were marked by multiple signs, including some that featured Manning’s name in bold neon letters, giving Manning’s restaurants and coffee shops a festive appearance at night. While this signage ensured that Manning’s customers could locate the company’s food and coffee, it also brightened the city blocks that hosted a Manning’s location.

In 2012, citizens of Los Angeles’ historic Highland Park neighborhood preserved and relit an abandoned Manning’s sign that sat atop Las Cazuelas Restaurant & Pupuseria on Figueroa Street, which began operating its restaurant there in 1985. According to one of the historic preservation professionals who helped restore the Manning’s sign, it was unique and historically significant because it featured “a rare combination of neon and opal glass letters” backlit by light bulbs.2 The sign was erected in 1936 and helped guide Manning’s customers to the location on Route 66 until the restaurant moved in the 1950s.

Early Manning’s billboard. Duke University Libraries.

But how did Manning’s get customers to their stores in the first place? Billboards along roadsides were another vital marketing tool, and Manning’s used them throughout the West Coast. But while Manning’s store signage was often bold and flashy, the company’s billboards tended to be minimalist, being little more than a reminder that Manning’s existed.

For example, a 1928 Seattle billboard touted the company’s name across the top, the tagline “fresh as the dawn” in the center, and a crowing rooster with coffee prices along the bottom. Other information, including Manning’s store addresses, was omitted. But apparently, this simple reminder was all that some customers needed to head to the grocery store for Manning’s coffee or swing by a Manning’s restaurant for coffee with a meal.

Manning’s “Taj Mahal” in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, 1960s. Family of Marty J. Brill.

In the company’s later, peak years, Manning’s also used Googie architecture as a marketing tool. For example, renowned architect Clarence Mayhew designed a Manning’s restaurant built in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood. The building, encompassing an entire block of Seattle’s Fifteenth Avenue Northwest, was so incredible that the Seattle Daily Times hailed it as “The Taj Mahal of Ballard.”

Seeking a dramatic effect, Mayhew designed the single-story building with an upswept, steeply pitched roof covered in laminated timber. Under the roof, large windows made of plate glass framed in cedar siding and aluminum sunscreens comprised the exterior walls. When describing the design to the Times, Mayhew called it “a marriage of Northwest and Polynesian long house in the idiom of Paul Bunyan.”3

The building opened in 1964 and quickly became a Seattle landmark—a routine stop for customers because the food quality was good, and the restaurant was “kind of like home.”4 It was hugely popular and was one of the last Manning’s restaurants to close in 1984. When long-time customers learned the restaurant was closing, they said it was “a sad finale for what was once a Puget Sound institution.”5 However, the building didn’t stay vacant long: Denny’s moved in and operated a restaurant there for the next 23 years. Sadly, developers wanted to replace it with an eight-story building, and so, despite fierce opposition, the Googie masterpiece was demolished when the chain moved in 2007.

Manning’s Denver location in the 1960s. Family of Marty J. Brill.

Signage and architecture inside Manning’s were also crucial in creating an inviting atmosphere that made customers feel at home. Using warm colors and cozy seating, customers felt comfortable visiting with companions, reading the newspaper, or studying for a final exam. People were encouraged to linger and treat Manning’s as another home where they could spend time and unwind.

Manning’s Denver location in the 1960s. Family of Marty J. Brill.

Despite Manning’s popularity, by the late 1960s, the company was at a competitive disadvantage. The restaurant industry evolved to emphasize fast food with drive-in service, and soft drinks became more popular than coffee. Facing a decline in profits, the Manning family decided to sell out to John Labatt, Ltd., a company based in Canada. Labatt’s primary interest was in Manning’s institutional food service, which merged with other divisions in Labatt’s company and continued to provide institutional food services for several decades after the sale. Labatt also operated several of Manning’s restaurants in Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco until 1984. Labatt sold Manning’s coffee to Continental Coffee Company, which became part of Sysco, a global foodservice company still operating with coffee as a significant part of its business.

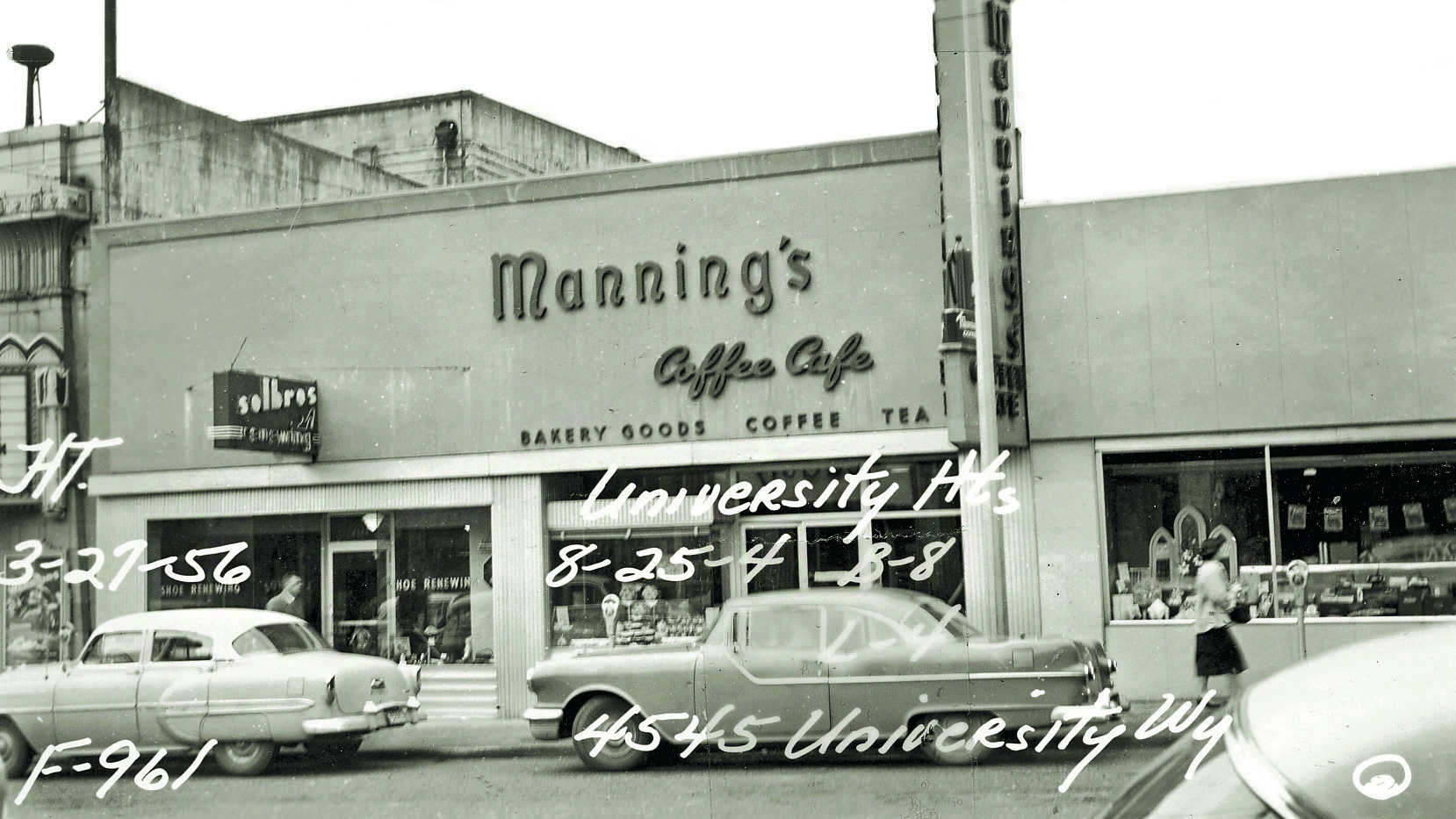

Manning’s University Way location in Seattle’s University Heights neighborhood, 1956. Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma, Stu Miller Collection.

Manning’s was a hugely successful business demonstrating the value of signage, billboards, and architecture in creating a successful marketing campaign. These tools are essential to brick-and-mortar locations, even in today’s digital environment. At Manning’s, these tools helped make its coffee shops and restaurants more than just a place to grab a java or a snack. For many customers, Manning’s restaurants were a place to hang out, a home away from home that enriched their lives.

About the Authors: Tracey Pemberton and Mike Elmore are researchers and partners in the consulting firm Locke & Kant, who recently published Manning’s: A Formula for Success, an e-book available from B&N. Tracey lives in Kansas City, Missouri, and Mike lives in Tacoma, Washington.

Footnotes

[1] Alice Shorett and Murray Morgan, Soul of the City: The Pike Place Public Market (University of Washington Press, 2007), 37-41; Alice Shorett, A History of the Pike Place Marketing District (Seattle Department of Community Development, 1972), 3-25.

[2] Nicole Possert and Amy Inouye, “Old Neon Glows Again in Los Angeles’ Historic Highland Park,” PreservationNation Blog (March 2012), 2.

[3] Staff Writers, “New Manning’s Cafeteria Set for Ballard,” Seattle Daily Times, February 3, 1963, and “Manning’s New Restaurant Called ‘Taj Mahal of Ballard,’” Seattle Daily Times, November 19, 1964.

[4] Smith, Carlton, “Adieu: Eatery’s end; To many, it’s familiar friend,” Seattle Daily Times, June 28, 1983.

[5] Ibid.

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2023, Vol. 41, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA