Landrum’s Diner in Reno, NV, is small, just 240 square feet, yet it plays an unusually large role in local history.

Although Landrum’s is well known among locals, especially those who were around during its heyday from the 1950s through the 1980s, few may recognize Landrum’s historical significance. As a hamburger diner built in the Art Moderne style, Landrum’s has a connection to the broader history of architecture and the development of diners. Its tiny size belies the role it plays at the convergence of architecture and hamburgers.

Pre-fabs in the Midwest

While diners trace their roots to New England, the birthplace of the American hamburger and the hamburger stand was in the Midwest, specifically Wichita, KS. White Castle Hamburger System was founded in 1921 by Walt Anderson, a Wichita fry cook who is credited with the invention of the hamburger. Anderson’s original hamburger “shack,” which opened in 1915, was a refurbished shoe repair shop with three stools, a counter, and a cast-iron griddle. The sign above the door announced, “Hamburgers 5¢.” By 1920, Anderson ran four stands and adopted the slogan, “Buy ’em by the Sack.” The next year, Anderson took on partner Billy Ingram, who proved to be a marketing genius. Under Ingram’s direction, the partnership was legally organized under the corporate name White Castle System of Eating Houses.1

On the strength of standardization, quality control, a commitment to cleanliness, and conservative financial practices, White Castle is credited with developing America’s passion for hamburgers and pioneering the take-out food business. In addition, White Castle is responsible for the development of portable all-metal buildings with porcelain-enamel coated exteriors, which became White Castle’s architectural corporate symbol. These were built by White Castle’s manufacturing division, the Porcelain Steel Building Company (PSB), which began in Wichita, but moved to Columbus, OH, along with, White Castle’s corporate offices, in 1935.2

Still, the portable steel building industry burgeoned in Kansas in the 1930s as a result of PSB’s developments and was the home of such portable metal building makers as Valentine Manufacturing, Inc., Butler Manufacturing Company (known for its popular military buildings ), and Beech Aircraft Company, which worked with, Buckrninster Fuller in 1944 to develop his concept of portable, inexpensive, light -weight Dymaxion House.3

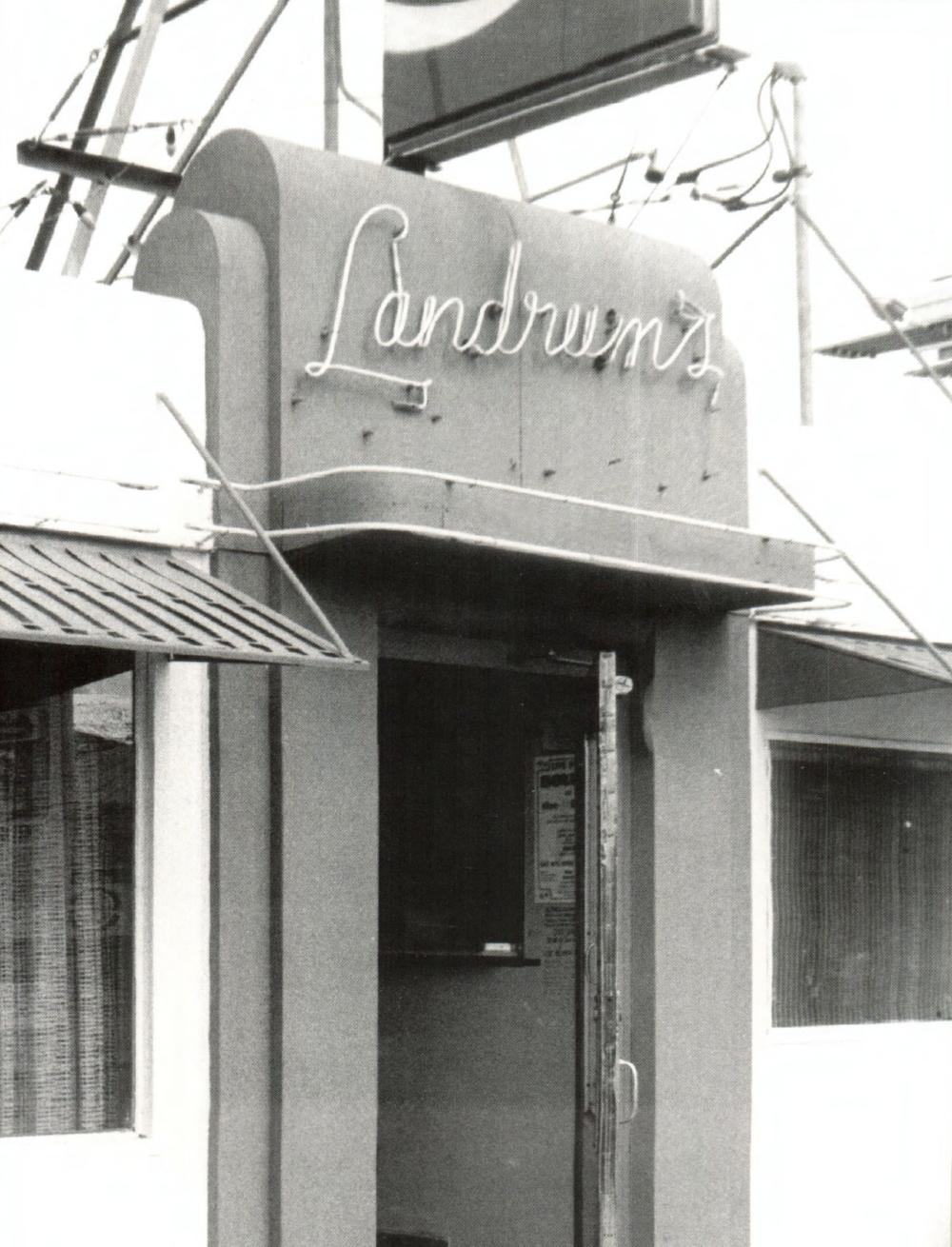

The diner in 1998. City of Reno Planning Department.

A number of “hamburger systems” copied the White Castle concept. The most blatant imitator was the White Tower Hamburger System, established in Milwaukee, WI, in 1926. The architectural styles employed by the two companies were strikingly similar, both boasting a tower and crenellated rooflines. Following a trade -infringement lawsuit lodged against White Tower by White Castle, White Tower’s castle design became stylized and streamlined in the Art Moderne fashion in order to distinguish it from White Castle.4 Most White Tower shops were small, and sited on busy street corners in urban areas. By the late 1940s, in keeping with the general post-World War II architectural trend for abstraction, White Tower buildings had developed into simple cubes that emphasized signs and glass, and the pure form of the building.5

Fifteen such buildings were built by the Valentine Manufacturing Company. White Tower’s chief architect, Charles Johnson, modified the basic Valentine frame into the most efficient White Tower ever built. The Valentine Company built the steel shell to White Tower’s plan and window arrangement, and sent it to the site where the foundation and utilities had been prepared. White Tower then arranged for the erection of the tower (their corporate symbol) and tile porcelain enamel cladding. The Valentine buildings offered size to fit the tightest urban location, as well as the visual impact needed for highway sites. Since they were prefabricated, the Valentine buildings allowed for ease of transport to a more lucrative location. The Valentine buildings’ main value to White Tower was the operational efficiency of the tight plan and the economy of construction. The Valentine buildings were originally intended to give 10 years of service, but, in fact, many lasted far longer.

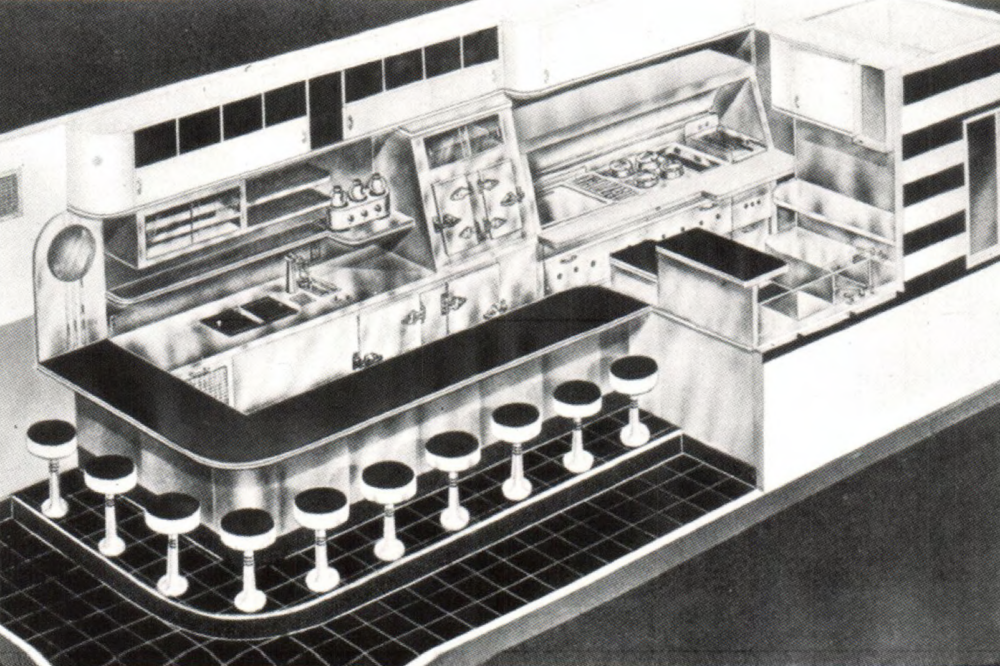

Valentine Manufacturing was founded by Arthur H. Valentine, a Wichita restaurant owner and promoter. A.H. Valentine had been operating the Valentine System of hamburger stands in Wichita, and in 1933 opened a new porcelain and steel structure on the corner of Beacon Lane and Market Street, which he named Valentine Lunch. The building was said to be the largest porcelain-steel structure ever built, and consisted of sections that were bolted together. Valentine Lunch was manufactured by the Metal Building Company of Wichita and the Martin Perry Company of New York.6 By 1938, Valentine had decided to manufacture his own design for small diners. He opened his plant in 1938 with six employees, producing prefabricated, stainless steel buildings for a variety of uses. Valentine’s most popular diner model was the Little Chef, which came in six-stool, eight-stool, and 10-stool sizes. The idea was for the unit to be complete and ready for business. All one needed was a piece of land on which to lay the foundation, and provide utility hook-ups. It was the perfect entrepreneurial activity for a country coming out of the Depression. These small diners made good economic sense, since they were one-man operations with limited menus. After World War II, small prefabricated diners offered ready investment opportunities for returning vcterans.7 Valentine’s stainless-steel sandwich shops were advertised as “new and modern.” The company has been described as, “The only major manufacturer west of the Mississippi. Practically all of the surviving handful of ‘real’ diners located in the West were built by Valentine.”8

Valentine also built its little modules for the White Tower chain, above ca. 1950.

Valentine continued to make diners after Arthur’s death in 1953, but the product line was expanded to include ice cream stores, liquor stores, portable dry-cleaning stations, turnpike toll booths, and filling stations. The diner design was enlarged from the original six-to 10-stool models costing about $3,300 in the 1940s, to a 40-seat model priced at more than $30,000 in the 1960s. The company closed in 1971, falling victim to competition from up-and-coming fast-food chains and changes in building codes. In the 33 years it was in operation, Valentine Manufacturing sold more than 2,200 sandwich shop s to buyers in every state except possibly Washington.9

The cutaway above is from a 1940s Valentine catalog. Diner Archives of Richard J.S. Gutman.

Reno in the Auto Age

Valentine’s contribution to Nevada was shipped to Reno via flat car in 1947. Landrum’s Hamburger System No. 1 is located on Reno’s main thoroughfare, where it still occupies its tiny triangular lot at 1300 South Virginia St. The diner sits at the extreme north west corner of the parcel, with no setbacks or landscaping, and a small parking area at the rear. Landrum’s was Valentine’s smallest model of sandwich shop, called the Little Chef, designed to accommodate from six to 10 customers, and intended to have been the first in a chain of hamburger restaurants. The restaurant was described as, “… absolutely the most fool-proof operation in the world. The only thing the customer had to do was run the foundation and hook up the electricity, gas, and sewer.”10 Valentine’s design was intended to allow a single operator to make a reasonable living from one unit.11 Landrum’s was typical of a large number of diners built across the United States, incorporating the Art Moderne style of the 1930s and early 1940s. Landrum’s, although its style was set by the manufacturer, conformed to the general manner in which Art Deco and Art Moderne styles were manifested in Reno during the 1930s and 1940s.

Landrum’s significance in local history can be discerned by examining Reno’s growth and development. Reno initially developed in the 1860s as a mercantile center for the distribution of supplies to the Comstock Lode in Virginia City and to nearby ranches. In 1869, with the completion of the transcontinental railroad, Reno grew in importance and, in 1872, it successfully captured the seat of Washoe County government from Washoe City to the south. Reno is bisected by the Truckee River that runs roughly east-west through town, and Virginia Street, running north-south. The railroad was established on the north side of the river, and the community began growing in that direction, with the earliest neighborhoods developing in the northwest and northeast quadrants. when the decision was made to establish the courthouse on the south side of the river, there were complaints because many felt the community would never grow in that direction. Nevertheless, that act established a trend for Reno to eventually grow to the south.

The southeast section of town, where Landrum’s Hamburger System No. 1 is located, began as an industrial and warehouse district. It was also the location of the Virginia and Truckee Railroad right-of-way. Residential growth in the southeast began in earnest after World War II. The area attracted young families who were able to purchase contemporary Ranch-style homes with the help of Veterans Administration financing. The neighborhood grew so rapidly after the war that a new elementary school was needed, the first new school to be built since the Depression.

View from 1998, shortly before the diner closed. City of Reno Planning Dept.

In addition to being part of the actively growing southeast quadrant of town, Landrum’s was situated along Reno’s main thoroughfare, Virginia Street, also known as U.S. Highway 395. In the 1930s, Reno’s economy was driven by the divorce trade, but after World War II, Las Vegas eclipsed it as a divorce destination. Reno turned to automobile tourism and casino gambling (which had been re-legalized in 1931) for its economic livelihood. The Lincoln Highway, which ran through Reno, opened up an active automobile-related tourist industry. According to the 1950 city directory,12 Reno catered to the tourist trade with 62 hotels and 80 motels, and numerous auto camps and guest ranches. Mid 20th-century commercial buildings in Reno’s downtown core generally focused on the gambling industry, and a number of building projects were undertaken following the war.

Along Virginia Street, between downtown and the city limits at Airport Road (now Plumb Lane), commercial activity in the 1940s and early 1950s was on a smaller scale and directed toward the surrounding neighborhoods and the automobile tourist. Motels, many of which had been auto courts in the 1930s, catered to travelers along Virginia Street. Polk’s 1950 Reno city directory13 identified the following business types operating within two blocks of Landrum’s: the Circus Potato Chip Company, a frozen food locker and barber shop, two beauty salons, two used-car lots, a supermarket, a drug store, a liquor store, two hardware stores, Sprouse-Reitz variety store, numerous dry cleaners, a bakery and candy store, a furrier, and a soda fountain. The commercial structure s that housed these businesses were utilitarian, single-story store front buildings, generally modest in size. The commercial block immediately north of Landrum’s, which remains today, was built in 1946 in a simplified Art Moderne style with green tile-clad engaged columns separating each unit. The diner, built a year later, complemented the style and color scheme of this store block.

View from 1998, shortly before the diner closed. City of Reno Planning Dept.

The sole diner

Landrum’s was brought to Reno on a flat car, off-loaded from the Virginia & Truckee Railroad track s behind the property, and assembled on its present site in 1947 by Eunice Landrum, who named her new diner, “Landrum’s Hamburger System No. 1. “The system was intended to be a chain of hamburger shops, but the original expansion plans never developed. Eunice Landrum sold the diner to Olive Calvert in 1953, who operated it until 1986. It has had a series of owners since, and was operated as the Chili Cheez Cafe until 1999 when it was leased by an automobile title loan business.14

Unfortunately, this last conversion resulted in the removal of all of the diner’s interior elements. Landrum’s was an “all-night” diner, where a traveler or swing-shift casino worker could get a meal around the clock. It was reported to have been a popular hangout for policemen. Reno’s 1950 police force consisted of 76 men and seven radio cars.15 With so small a force, a restaurant the size of Landrum’s was more than adequate to accommodate patrolmen on their lunch and dinner breaks. Over the years, the police used the diner as a place to sober up drunks so they would not have to be jailed.16 The diner was also a popular destination for teenagers seeking a late-night meal after a party or the movies. Landrum’s had a good reputation and the stools were always filled.

Besides hamburgers, favorite menu items included bacon and eggs, and omelets. Landrum’s famous chili-cheese omelet was created by longtime waitress Daisy Mae Wright, who claimed, “A bar owner came in one day and said he wanted a chili bean omelet, so I fixed him one. He started telling everybody about it, and soon the word spread. We even had to hire somebody to come in and grate the cheese.”17 Wright introduced another element to dining at Landrum’s, her personal philosophy on dealing with customers: “I yell and scream at them all the time. If I am not screaming, they think I am sick or something. I really give them hell if they use bad language, especially if there are women around.”18 One waitress could handle a full house at Landrum’s. Although there were eight stools at the counter, veteran customers knew that only six would accommodate humans. “The one at the north end has no knee room, and the cigarette machine pokes you in the back, and the one at the bend in the counter wobbles.”19 The wobbly stool may have contributed to one unfortunate incident when a drunk fell off his stool and broke one of the two large windows.20 A metal-frame roof sign announced that Landrum’s was “Reno’s Original Diner.” Landrum’s was Reno’s only true diner, which made it somewhat of a novelty and contributed to its popularity.

Landrum’s Hamburger System No. 1 represents Reno’s participation in the “diner fever” that swept the U.S. from the 1920s through the 1940s. Landrum’s was built in the image of the popular and successful hamburger diners of the Midwest and East. Even its siting, on a busy street corner with no setbacks or landscaping, copied the proven arrangements of White Castle and White Tower properties. Reno has long been known as “The Biggest Little City in the World,” and with a “new and modern “stainless-steel diner, Renoites could share a cultural connection with larger urban centers. Landrum’s was typical of the popular small diners of its era. It incorporated the standard Valentine design that included a two-color porcelain enamel envelope, a small but space-efficient interior, and diminutive buttresses. Landrum’s, with its fluid Art Moderne lines, rounded corners, and unique use of building materials, is the singular representative Valentine diner in Nevada, and one of but a few remaining anywhere in the West.

The diner’s significance, both architectural and historical, is being recognized today. Several diners have been listed in the National Register of Historic Places, including Landrum’s in 1998. Landrum’s has been a landmark for three generations of Reno citizens. In 1984, when Landrum’s was but 37 years old, it was listed in the Nevada State Register of Historic Places. In honor of state recognition, Nevada Governor Richard Bryan,21 a self-proclaimed hamburger aficionado, visited Landrum’s and sampled the fare. Of the hamburger, Bryan said, “The bun is fresh. The beef is tasty. The lettuce is crispy. The tomato is firm. And the onion is tangy.” He liked the diner’s history even more: “This is a Reno legend. In the 1920s and 1930s, diners like this were everywhere. This is the last of its kind. It is a part of Americana and I hope they keep it here forever.” 22

About the Author: Mella Rothwell Harmon is an historic preservation specialist with Nevada’s State Historic Preservation Office, she chairs the Reno Historical Resources Commission, and is a member of Nevada’s Statewide Transportation Technical Advisory Committee. Harmon has worked as an appraiser, archaeologist, project administrator, grants administrator, and architectural historian. She served as research assistant on The Buildings of Nevada, due out this year by Oxford University Press and the Society of Architectural Historians.

Harmon is also the author of Landrum’s Hamburger System No. 1, which includes many additional photos.

Endnotes

[1] David Hogan, Selling’em by the Sack: White Castle and the Creation of American

Food (NY: New York University Press, 1997), 26-38.

[2] Hogan, 26-38.

[3] Robert Snyder, Buckminster Fuller: An Autobiographical Monologue/Scenario (NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1980).

[4] Hogan, 52-56.

[5] Paul Hirschorn and Steven lzenour, White Towers (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1981 ), 20.

[6] Wichita Beacon, Thursday, Oct. 26, 1933, 11.

[7] Richard Gutman, American Diner: Then and Now (NY: Harper Perennial, 1993 ), 105.

[8] Gutman, 110.

[9] Gutman, 110.

[10] Becky Tanner, Wichita Eagle, Aug. 18, 1994.

[11] Gutman, 109.

[11] R.L. Polk, Reno City Directory (San Francisco: R.L Polk and Company, 1950 ).

[13] Reno City Directory.

[14] Angela Curtis, Sparks Tribune, Sunday, Oct. 3, 1993; Lila Fujimoto, Reno Gazette-Journal,

Feb. 29, 1984, 1-2D; Gayle Fisher, Reno Evening Gazette, May 28, 1978, 52.

[15] Reno City Directory.

[16] Gayle Fisher, Nevada State Journal, May 28, 1978.

[17] Cory Farley, Reno Gazette-Journal, Aug. 1, 1986.

[18] Reno Gazette-Journal.

[19] Reno Gazette-Journal.

[20] Nevada State Journal.

[21] Richard Bryan is currently a U.S. senator (D) from Nevada.

[22] Reno-Gazette-Journal.

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2000, Vol. 18, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA