On the evening of September 15, 1885, tragedy befell the world: Jumbo the elephant, superstar of the Victorian era and P.T. Barnum’s circus sensation, was dead.

Beloved by millions, Jumbo’s distinctive and catchy name became a means of conveying any object’s enormous size, and quickly entered the lexicon of everyday speech. His broad appeal stimulated a marketing frenzy of his name and image across an astonishing range of product brands, many of which played on the size association: peanuts, popcorn, and hot dogs, to name a few. It is probable that Jumbo was the inspiration behind three zoomorphic architectural creations in New York and New Jersey, and his influence has carried on beyond his lifespan as the stimulus, for example, behind Walt Disney’s Dumbo.

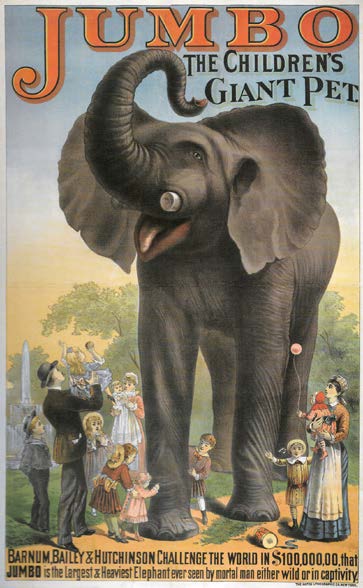

Jumbo, The Children’s Giant Pet. Produced by the Hatch Lithographic Company of New York, this poster was designed for use upon Jumbo’s arrival to the city in April 1882. Jumbo’s actual height was a carefully guarded secret and exaggerated with promotional hype by Barnum—to the extent that photographs of the pachyderm were forbidden. Jumbo’s height based on modern bone analysis suggests that he was approximately 10.5 feet tall, measured to the shoulder—about 20% bigger than what he should have been for his age. However, Jumbo had approximately 16 more years of growth to maturity. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art.

Born in late 1860, Jumbo was captured in the remote desert highlands straddling the border between eastern Sudan and Eritrea (then Abyssinia) early in 1862 by Hamran tribesmen, nomadic hunters who dealt in ivory, bone, and hides but more recently began securing live animals for Europe’s thriving zoos and circuses. After a grueling 6,700.mile trek on foot, in the stifling cargo holds of steamers, and cramped cages in railway cars, Jumbo was sold to the Jardin des Plantes, the Paris Zoo, in February 1863. At just over four feet tall, Jumbo was anything but impressive and languished in the shadow of more popular creatures in the elephant rotunda, unloved and poorly cared for.

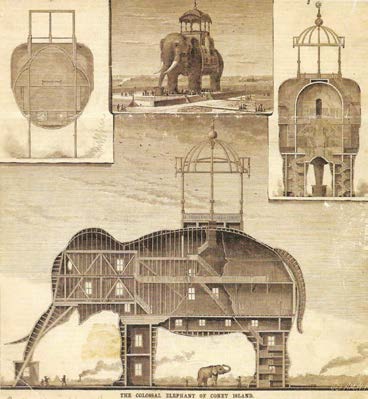

Top: The Colossal Elephant of Coney Island. The elephant at bottom is presumably Jumbo, included to provide a scale of reference. Scientific American, July 11, 1885. Above: Lucy the Elephant, Margate City, New Jersey. Photo by author, September 2012.

In the summer of 1865, Jumbo was traded to the London Zoological Society and received in a filthy and diseased condition. One theory as to how Jumbo got his name is that his deplorable state upon arrival called to mind the disheveled appearance of Mumbo Jumbo, a West African tribal holy man. That said, the origin of his name and as to whether it was bestowed in London or Paris remains a mystery.

By 1871 Jumbo’s health had improved and he became a top attraction at the London Zoo in Regent’s Park. Becoming the “Children’s Pet” for over a decade, he paraded kids around seven days a week on afternoon rides. Among the more than one million said to have ridden on his back were Queen Victoria’s son and daughter, Prince Leopold and Princess Beatrice, Winston Churchill, and Theodore Roosevelt. It was during his time at the London Zoo under the care of his devoted keeper, Matthew Scott, that Jumbo developed into his reputed size as the largest elephant in captivity.

Jumbo, The Children’s Giant Pet. Produced by the Hatch Lithographic Company of New York, this poster was designed for use upon Jumbo’s arrival to the city in April 1882. Jumbo’s actual height was a carefully guarded secret and exaggerated with promotional hype by Barnum—to the extent that photographs of the pachyderm were forbidden. Jumbo’s height based on modern bone analysis suggests that he was approximately 10.5 feet tall, measured to the shoulder—about 20% bigger than what he should have been for his age. However, Jumbo had approximately 16 more years of growth to maturity. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art.

Born in late 1860, Jumbo was captured in the remote desert highlands straddling the border between eastern Sudan and Eritrea (then Abyssinia) early in 1862 by Hamran tribesmen, nomadic hunters who dealt in ivory, bone, and hides but more recently began securing live animals for Europe’s thriving zoos and circuses. After a grueling 6,700.mile trek on foot, in the stifling cargo holds of steamers, and cramped cages in railway cars, Jumbo was sold to the Jardin des Plantes, the Paris Zoo, in February 1863. At just over four feet tall, Jumbo was anything but impressive and languished in the shadow of more popular creatures in the elephant rotunda, unloved and poorly cared for.

Top: The Colossal Elephant of Coney Island. The elephant at bottom is presumably Jumbo, included to provide a scale of reference. Scientific American, July 11, 1885. Above: Lucy the Elephant, Margate City, New Jersey. Photo by author, September 2012.

In the summer of 1865, Jumbo was traded to the London Zoological Society and received in a filthy and diseased condition. One theory as to how Jumbo got his name is that his deplorable state upon arrival called to mind the disheveled appearance of Mumbo Jumbo, a West African tribal holy man. That said, the origin of his name and as to whether it was bestowed in London or Paris remains a mystery.

By 1871 Jumbo’s health had improved and he became a top attraction at the London Zoo in Regent’s Park. Becoming the “Children’s Pet” for over a decade, he paraded kids around seven days a week on afternoon rides. Among the more than one million said to have ridden on his back were Queen Victoria’s son and daughter, Prince Leopold and Princess Beatrice, Winston Churchill, and Theodore Roosevelt. It was during his time at the London Zoo under the care of his devoted keeper, Matthew Scott, that Jumbo developed into his reputed size as the largest elephant in captivity.

There’s more! To read the rest of this article, members are invited to log in. Not a member? We invite you to join. This article originally appeared in theSCA Journal, Fall 2018, Vol. 36, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA