The River Attractions of Niagara Falls

The River Attractions of Niagara Falls

REGISTRATION NOW OPEN!

SCA’s 48th Annual Conference

in Niagara Falls

June 18-June 21

A guaranteed barrel of fun!

“Let’s go again to Niag’ra, This time we’ll peek at the Fall.” So sang Frank Sinatra in “Let’s Get Away from It All,” although I am not sure what preoccupied him on that first trip.

Going Behind the Sheet

The first account of going behind the Horseshoe Falls dates to April 1753 when Jean Carmine Bonnefons, an intrepid individual, descended the perilous 160-foot Niagara Gorge by clinging to bushes, trees, roots, and rock outcrops. Once at the bottom, he clambered over slippery rocks and ventured behind the Falls for 40 feet until dangerous crevices blocked his passage. During the ordeal, Bonnefons was buffeted by wind and spray and rattled by the deafening roar.1

In subsequent years, access was improved slightly using “Indian ladders,” large trees carved with notches for the feet and branch stubs serving as handholds. Tipped over the gorge edge and wedged into an upright position, the daring could clamber down to the riverbank, where the views were said to be the most sublime. Although, as historian William Irwin relates, “Even on the ‘improved’ ladder of 1805, one traveler noted that the swaying sent him hanging perpendicular to the cliff high above the river.”2

In 1818, William Forsyth, the first entrepreneur in the burgeoning tourist business at Niagara Falls, constructed a covered staircase to the base of the cataract for which he presumably charged a fee. In 1827, businessmen Thomas Clark and Samuel Street took over Forsyth’s stairs and immediately proceeded to sublet them along with the right to conduct people behind the Falls. They erected several buildings, one of which contained dressing rooms where tourists were outfitted with waterproof oilskins for the journey. Another was a barroom at the top of the stairway. There was no charge for the clothing, but it was expected that tourists would spend money at the bar.3

The area adjacent to the Horseshoe Falls (known as Table Rock, a large rock overhang) and the land immediately downriver was fast becoming a place of unprincipled Competition for the tourist dollar. In 1827, Thomas Barnett established a museum at Table Rock. In short order, he built his own stairway adjacent to Clark and Street’s and guided visitors behind the Falls – established now as a named tourist attraction: Trip Behind the Great Falling Sheet of Water. At this time, the distance one could venture was 153 feet, ending at Termination Rock, a huge limestone rockfall that prevented further passage.4 In 1853, Saul Davis, the most unscrupulous operator of the era, built the Table Rock House immediately south of Barnett’s Museum, with whom he had a fierce rivalry. He, too, built a competing staircase down the gorge and provided guided tours behind the cataract. The cost of tours, photographs, and souvenirs was grossly mispresented on arrival; those who did not pay the exorbitant prices when it came time to leave were threatened and abused, both verbally and physically.5

The commercial accretions along the gorge, piling up year over year, became known as the Front. As historian Pierre Berton notes, it was a “notorious quarter-mile strip, just three hundred yards wide, that ran from Table Rock to the Clifton House Hotel and provided a haven for a half a century for every kind of huckster, gambler, barker, confidence man, and swindler. Here half a dozen hotels sprang up along with a hodgepodge of other shops, booths, and taverns.”6

Over the years, a groundswell of public agitation concerning unethical operators and crass commercialism in an astoundingly beautiful setting led to the creation of Queen Victoria Park, occupying land adjacent to the gorge, in 1885 (opening in 1888). The new operating body, the Niagara Parks Commission, razed most of the buildings but maintained Table Rock House as it was closest to the Falls. More importantly, the commissioners recognized that the Behind the Sheet attraction was extremely popular and a good source of revenue to be had in the absence of government funding to help maintain the new park.7

In 1887, the staircase was replaced by a hydraulic elevator, and in the following year, a tunnel was driven around Termination Rock to extend the distance accessible behind the Falls. Unfortunately, in 1889, a series of rockfalls (combined with low lake levels) resulted in a recession of water from the Canadian flank of the Falls. With little water going over the precipice, walking Behind the Sheet was no longer a viable attraction. Ever mindful of revenue, the commissioners decided to bore a tunnel through bedrock behind the Falls. Emerging at a portal beyond Termination Rock, visitors could view the falling water safely and all year long. In 1902, the tunnel was extended 800 feet, and an elevator was built to connect directly with Table Rock House.8

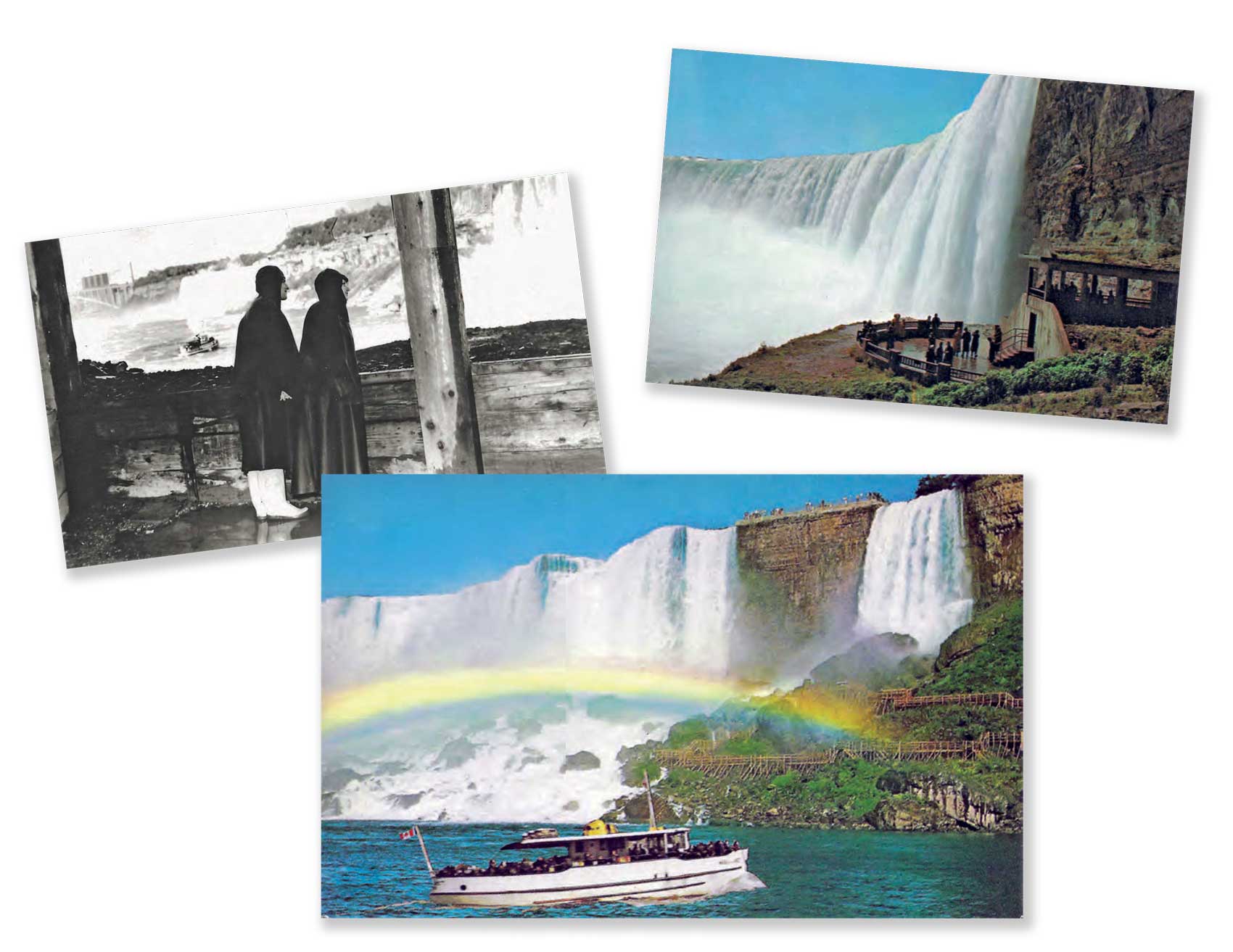

In 1944, an inspection of the tunnel revealed that the recession of the Falls in the intervening years had brought the face of the gorge to within six feet of the tunnel in places. As a result, a new tunnel was cut 60 feet back from the original, lined with concrete, and outfitted with electric lighting (the original tunnel required guides with lanterns to escort visitors). Today, the attraction is known as Journey Behind the Falls, and the experience offers three close-up views of the Falls: two from tunnel portals and one from an outdoor observation plaza at the foot of the Falls.9

Cave of the Winds

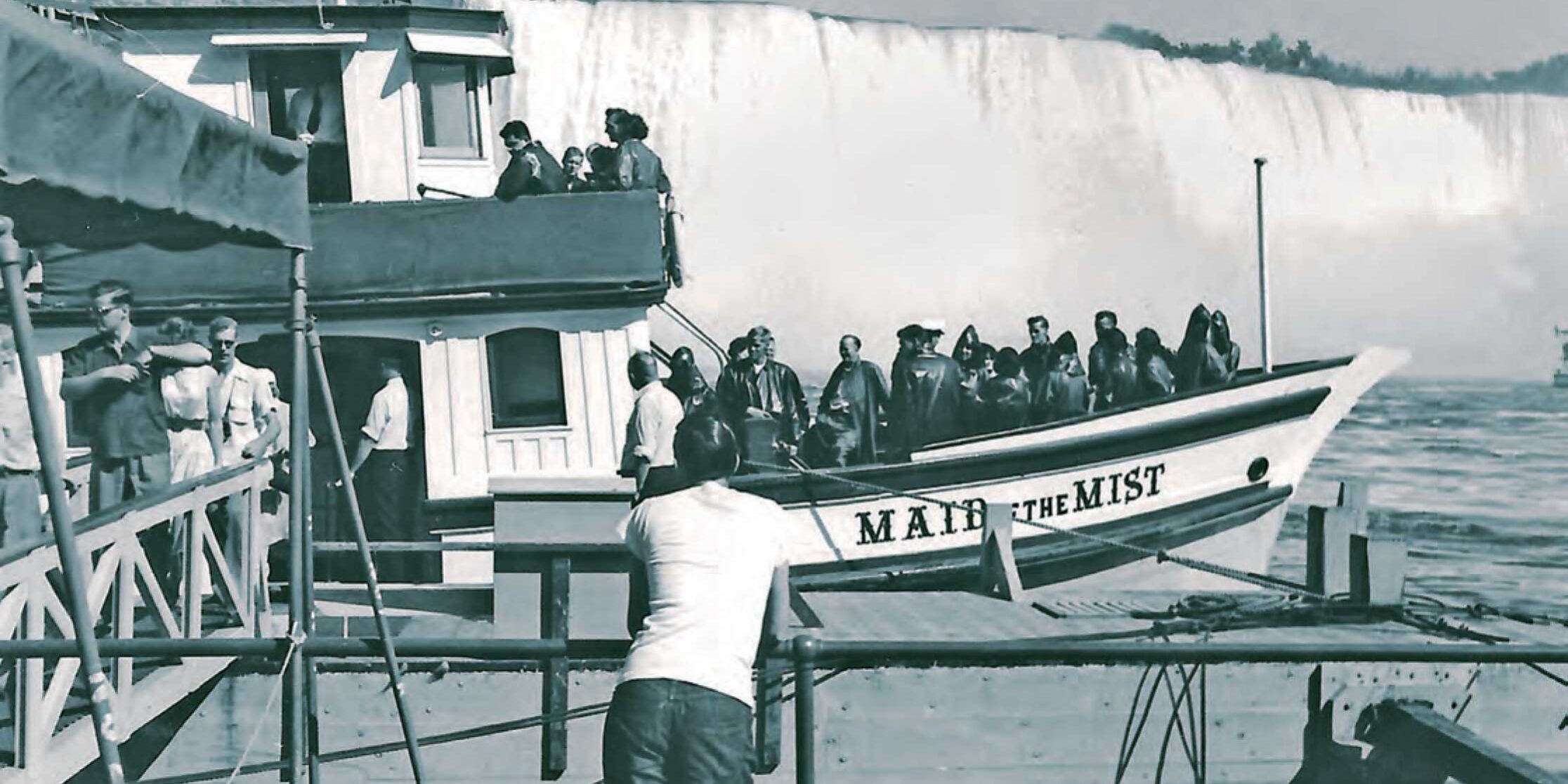

During the mid-19th century, adventurous spirits could not say that they had “done Niagara” until they had experienced Cave of the Winds and the Maid of the Mist, among other specific attractions. Discovered in 1813 and originally called Aeolus’s Cave (after the Greek God of Wind), Cave of the Winds was a large overhang of hard dolomite stone that extended a considerable distance behind Bridal Veil Falls (the small cataract between the American and Horseshoe Falls) on the American side. In 1840, guidebook writer Horatio Adams Parson described the cave as “about 120 feet across, 50 feet wide, and 100 feet high” and very rough in nature.10

There’s more! To read the rest of this article, members are invited to log in. Not a member? We invite you to join. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2025, Vol. 43, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA

About the author: Peter Glaser is the long-time writer of this journal’s “Northern Roadsides” column.

Footnotes

[1] George A. Seibel, “River of Pleasure,” in Niagara—River of Fame, ed., William J. Holt (Niagara Falls, Ontario: Kiwanis Club of Stamford, 1968), 261.

[2] William Irwin, The New Niagara: Tourism, Technology, and the Landscape of Niagara Falls, 1776-1917 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996), 3.

[3] George A. Seibel, Ontario’s Niagara Parks: 100 Years (Niagara Falls, Ontario: The Niagara Parks Commission, 1985), 6; Niagara—River of Fame, 261. Forsyth was the proprietor of the Pavilion, the best known of the early hotels on the Canadian side of the river.

[4] Sherman Zavitz, It Happened at Niagara (Niagara Falls, Ontario: Lundy’s Lane Historical Society, 2010), 86.

[5] Ontario’s Niagara Parks: 100 Years, 12-13.

[6] Pierre Berton, Niagara: A History of the Falls (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1992), 54; Gordon Donaldson, Niagara! The Eternal Circus (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1979), 153. The Front was later reincarnated in a more legitimate way, with Clifton Hill as its nucleus, comfortably set back from the Falls.

[7] Ontario’s Niagara Parks: 100 Years, 83.

[8] Ibid, 83-88; Ronald L. Wray, Ontario’s Niagara Parks: A History, 2nd Edition (Niagara Falls, Ontario: The Niagara Parks Commission, 1960), 65, 125-126.

[9] Ontario’s Niagara Parks: 100 Years, 88.

[10] Horatio Adams Parson, Steele’s Book of Niagara Falls (Buffalo: Oliver G. Steele, 1840), 37.

[11] The staircase, circular and enclosed, was erected by Nicholas Biddle of Philadelphia, president of the Bank of the United States.

[12] Steele’s Book of Niagara Falls, 38.

[13] Karen Dubinsky, The Second Greatest Disappointment: Honeymooning and Tourism at Niagara Falls (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1999), 49-50.

[14] Ginger Strand, Inventing Niagara: Beauty, Power, and Lies (New York: Simon & Schuster: 2008), 168-169.

[15] George A. Seibel, The Niagara Portage Road: A History of the Portage on the West Bank of the Niagara River (Niagara Falls, Ontario: The City of Niagara Falls Canada, 1990), 112.

[16] Ibid., 116-118; Ralph Greenhill and Thomas D. Mahoney, Niagara (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969), 110-111.

[17] Quoted in Niagara, 111.

[18] The Niagara Portage Road, 118-119.

[19] “River of Pleasure,” in Niagara—River of Fame, 286.

[20] Ibid., 287-288.

[21] The New Niagara, 86. Olmstead was instrumental in advocating for the preservation of Niagara Falls as well as the design and planning of the New York Reservation on the American side; Albert H. Tiplin, Our Romantic Niagara: A Geological History of the River and the Falls (Niagara Falls, Ontario: Niagara Falls Heritage Foundation, 1988), 81.

[22] Niagara—River of Fame, 286-287; It Happened at Niagara, 87-88.

[23] Ontario’s Niagara Parks: 100 Years, 174-184.

[24] Ibid., 190; Ontario’s Niagara Parks: A History, 140-141.

[25] It Happened at Niagara, 164.

[26] Ontario’s Niagara Parks: 100 Years, 117.

[27] The New Niagara, 65.

[28] William Pryor, “Niagara Falls by Night,” in Niagara—River of Fame, 305. Candlepower is a unit of measurement for luminous intensity.

[29] The New Niagara, 99.

[30] Ontario’s Niagara Parks: 100 Years, 123. For example, several brochures from the 1960s used the same promotional copy, advising, “To see the illumination at its best, spend the night at Niagara Falls … where modern hotels meet the needs of every traveler.”

[31] Ontario Hydro, “Floral Clock,” in Niagara—River of Fame, 308-309; Ontario’s Niagara Parks: 100 Years, 309-310.