Around 200,000 tourists visit Green Gables annually. Photo by author, April 2022.

“All my life it has been my aim to write a book… I have always kept a notebook in which I jotted down… ideas for plots, incidents, characters, and descriptions. Two years ago, in the spring of 1905 I was looking over this notebook in search of some suitable idea … and I found a faded entry, written ten years before: ‘Elderly couple apply to orphan asylum for a boy. By mistake a girl is sent them.’”

~ Lucy Maud Montgomery

Lucy Maud Montgomery (1874-1942). In addition to Anne of Green Gables, Montgomery wrote 19 novels (including seven sequels) and hundreds of short stories, poems, and essays. When Montgomery was 21 months old, her mother died of tuberculosis, and her father placed her in her maternal grandparents’ custody. After her grandmother died in 1911, Montgomery moved to Ontario and married Ewen Macdonald, a Presbyterian minister. All images from the author’s collection except where noted.

The result was Anne of Green Gables.1 This best-selling novel was published in June 1908 and achieved instant acclaim, with seven impressions printed before the year’s end. Much of the appeal was the creation of Anne Shirley—a spunky, independent, and intelligent heroine with a fertile imagination. As Mark Twain noted, Anne was “the dearest and most loveable child in fiction since the immortal Alice” of Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland.2

Lucy Maud Montgomery had created a charming portrait of Cavendish, Prince Edward Island (PEI)—a typical rural island community with a church, cemetery, school, and post office—which she transformed into the fictitious village of Avonlea. This place would come to hold special meaning for many the world over. The popular reception of Anne of Green Gables “churned up so much attention that her home province … soon had a flood of visitors, all wanting to see the landscapes she painted so vividly.”3 Indeed, no fictional character has ever contributed so dominantly to a province’s tourism as red-haired, pig-tailed Anne.

Those who came were intent on seeking out the sacred sites: the buildings and pastoral locales surrounding Montgomery’s ancestral home on the Island’s North Shore. In the summer of 1909, Montgomery noted, “I owe much to that dear lane [Lovers’ Lane, one of her Cavendish haunts]. And in return I have given it love—and fame. I painted it in my book: and as a result, the name of this little remote woodland lane is known all over the world. Visitors to Cavendish ask for it and seek it out. Photographs of its scenery have appeared in the magazines. The old lane is famous.”4

Locals, including family, did not always appreciate the influx of visitors to pilgrimage sites. For example, in 1920, Montgomery learned that her uncle John F. MacNeill was tearing down the house where she had been raised.

Sightseers regularly trespassed all over the property, “peering into the windows of the empty house and trampling all over his planted fields.”5 While Montgomery did not get along with her uncle, she was “content that it should be torn down. It would not please me to think of it being overrun by hordes of curious tourists and carried off piecemeal. The Bentley party had their car full of some old junk they had retrieved from the cellar!”6

The character of the Island changed dramatically in the post-war years because of tourism, much of which was inspired by Montgomery’s novel. Cavendish residents noted the surge of visitors, and a handful began catering to the summer trade. In 1921, Jeremiah and Christianna Simpson were the first to accommodate tourists as a sideline to their farm operation. The following year, Ernest and Myrtle Webb (elderly cousins of Montgomery), who lived in a neighboring farmhouse that had inspired the novel’s setting—and would soon become “Green Gables,” Canada’s most famous literary landmark—opened a tearoom and began taking guests. In short order, they would add cabins, provide tours of the area, and sell souvenirs, such as picture postcards. Others followed, such as Katherine Wyand, who offered accommodation and opened the Avonlea Restaurant, a lunch counter right at the beach.7

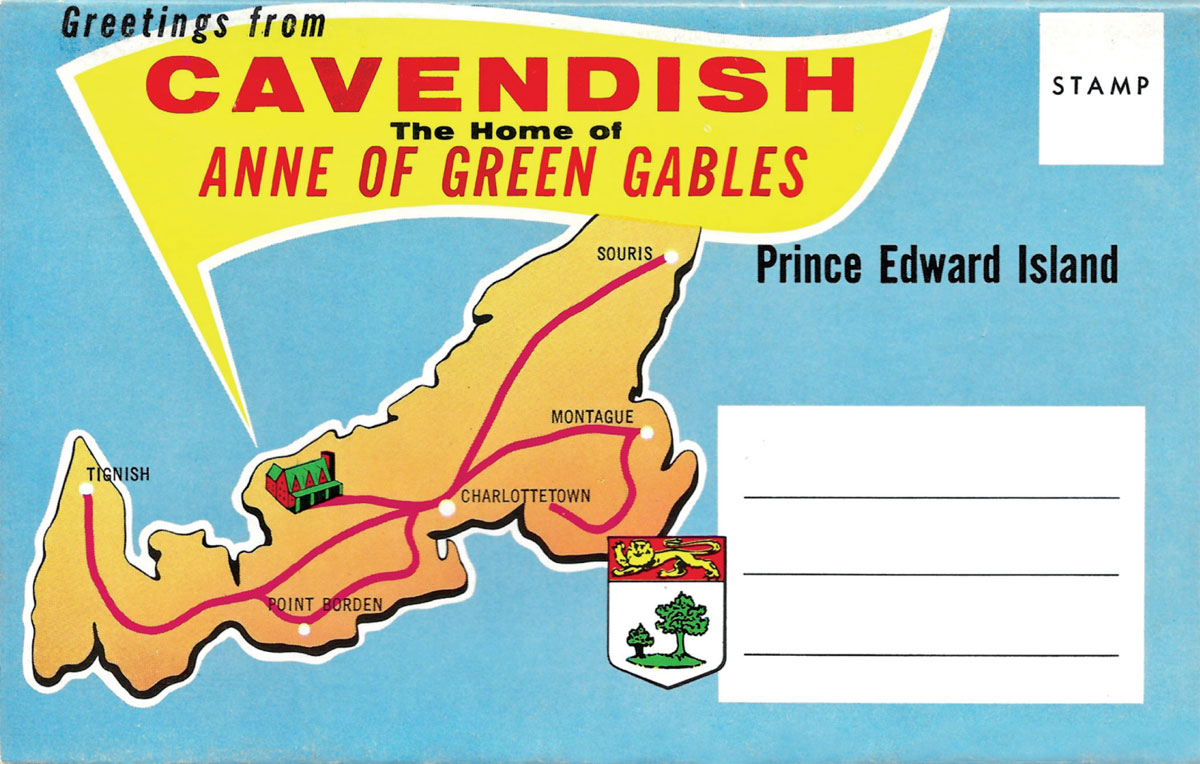

A c. 1960s Cavendish postcard folder. No mention of the author here, just the tourist imperative: “The Home of ANNE OF GREEN GABLES.”

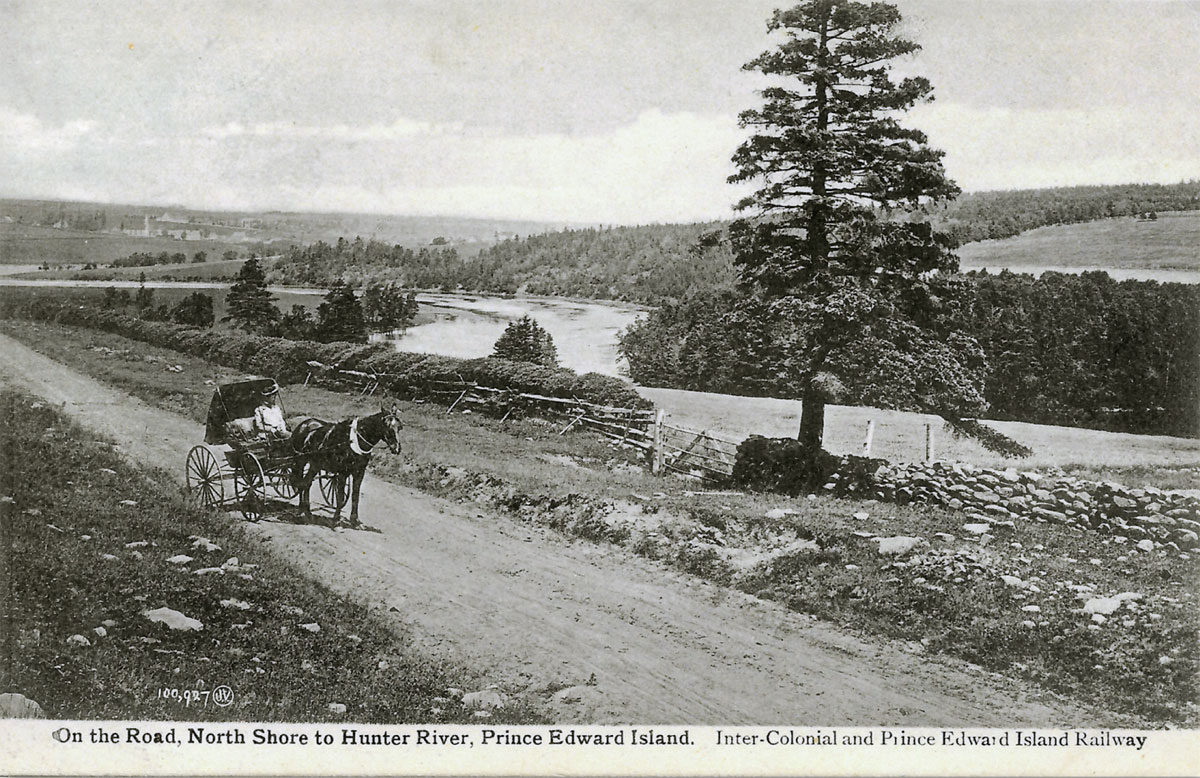

Horse and buggy, c. 1900. Readers of Anne of Green Gables will appreciate that this view evokes Matthew Cuthbert’s ride to Bright River (modeled on Hunter River) to pick up the orphan and return to Avonlea on the North Shore (based on Cavendish).

Visiting the Island in 1929, Montgomery noted: “It was dark when we got to Hunter River [the closest train station to Cavendish] and there was a light in the waiting room…. On the opposite wall thro’ the door I saw a big poster—“Avonlea Restaurant, Cavendish Beach.” Mrs. Allan Wyand … has been turning an honest penny this summer by catering to the summer crowds that come to the sand shore…. One day this summer I understand there were all of two thousand people there.”8

While Montgomery was initially proud of the attention she had given to the Island’s North Shore, by the late 1920s, she was appalled by it: “You ask in your letter if ‘Cavendish has become a place of pilgrimage for my admirers?’ Alas, yes. And the chagrin expressed in that alas is not affectation at all but genuine regret and annoyance. Cavendish is being over-run and exploited and spoiled by mobs of tourists and my harmless old friends and neighbors have their lives simply worried out of them by carloads of “foreigners” who want to see some of Anne’s haunts. I was down home a month this summer and there was hardly a day that was not spoiled for me by some irruption.”9

Cover of the 1950 PEI National Park brochure when golfing took precedence. Green Gables is adjacent to the 18th green.

In the mid-1930s, a movement began to create a national park in PEI; until then, there was no national park east of Ontario. Dalvay-by-the-Sea, an oceanfront mansion in Grand Tracadie, 20 miles east of Cavendish, was considered a logical choice for inclusion to attract affluent tourists. Built in 1896 as the summer home of American millionaire Alexander McDonald, a one-time president of Standard Oil, its acquisition would fit perfectly into the tradition of majestic park hotels like those in Banff and Jasper.10 Senior Parks Canada staffer Frank H.H. Williamson envisioned creating a classic seaside resort without the typical “obnoxious amusements.”11

Of course, it was soon apparent that it would be impossible to ignore the mass appeal of Cavendish in any national park development plan for the Island. A newspaper report in the late 1920s emphasized the significance of the area, noting, “More tourists have visited the scenes of L.M. Montgomery’s novels this year than ever before and the prospects are that there will be an ever-increasing number of visitors.” It went on to state that signs to the sites were needed. Moreover, the sites themselves required protection from “people who do not appreciate the value of literary associations as a commercial asset.”12

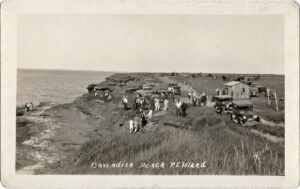

Cavendish Beach, c. 1920s. The small building is a food concession stand. Courtesy Phil Culhane, www.peipostcards.ca/.

Parks Canada was won over by Cavendish, mainly because of its connection to the Anne books. Williamson offered suggestions on developing the area, many of which were obnoxious amusements—the very thing to be avoided at Dalvay. His ideas included a children’s village; Green Gables as a children’s rest house with a museum; aquarium; buildings for dancing and roller skating; a carnival arena; concessions for bungalow camps, hotels, restaurants, soft drinks, and ice cream; beach donkeys and ponies; moving picture theatres, and other shows.13

By July 1936, Prince Edward Island National Park had been finalized: 25 miles of oceanfront land that took in the prime beaches along the North Shore. Green Gables would be the centerpiece. On learning in September 1936 of three Cavendish farms that would be expropriated for inclusion in the park, Montgomery wrote: “I feel dreadfully. Where will the Webbs go? Another home I have loved blotted out. Everything changed. I understand these farms were chosen because of Anne of Green Gables. It’s a compliment I well could spare.”14

As it turned out, the Webbs, who had expanded their accommodation business by adding cottages in the early 1930s, sold Green Gables with the promise of a $50 per month job for Ernest to serve as caretaker in the new park. They were also permitted to remain living at the farmhouse until 1945. As for Katherine Wyand, things did not go so smoothly. By the late-1920s, Wyand had built Avonlea Cottages, renting out cabins by the day or week. Initially permitted by Parks Canada to continue her business, they rescinded the offer as her cottages did not meet park standards. Nevertheless, Wyand refused to move and mounted a formidable public relations campaign through the press before being expropriated.15

Parks Canada was rather short-sighted in its planning of the national park, for, in its creation, it had eliminated most of the cottages and rooms available for rent. Pressured to accommodate an anticipated surge of tourists (visitation to the park would jump from 2,500 in 1937, its inaugural year, to 37,000 in 1939), Parks Canada awkwardly approached tourism operators they had just expropriated. Katherine Wyand took the offer “to reopen her cottages in the park once they were moved further off the beach, cleaned up, and painted.”16

Dalvay-by-the-Sea Hotel contains 25 guestrooms and eight three-bedroom cottages. Photo by author, April 2022.

Oddly enough, while Parks Canada recognized the growing iconic value of Green Gables, the site initially took a subordinate role in the development of the new park. Instead, taking priority was creating a golf course, which, during the era, was seen as crucial in making the park credible as a cultured destination.17 As a result, the outbuildings and agricultural landscape of Green Gables were destroyed, sparing only the famous farmhouse—and it only narrowly escaped becoming the clubhouse for the golf course. The fairways were laid out perilously close to the house, the gables of which were painted green for the very first time with shutters added.18

A c. early-1950s scene at Cavendish Beach. In the foreground are a bathhouse and kitchen shelter. Avonlea Cottages and the dining room are in the background. This picture was taken from the vantage point of a sand dune at the beach’s edge.

Parks Canada can be somewhat forgiven for its negligent planning of the site. After all, the reality of Green Gables is befuddling. As Brenda R. Weber perceptively articulated: “let’s be clear what we’re talking about here: fans flocking to a site they believe to be the ‘real’ home of a fictional girl they’ve grown to love, an author’s imaginary becoming so strong and seemingly real that a national park is established on the site of where events never took place but were said to have.”19

It was not until 1950 that Green Gables was formally opened to the public, initially as a museum with a tearoom and gift shop furnished to re-create “the home” of Anne Shirley. The farmhouse had been built in 1831, with additions in the 1870s and 1914, but its interior was decorated to represent the 1890s, the era of the novel. Parks Canada’s interpretive policy at Green Gables recognized that historical authenticity must sometimes be compromised by literary accuracy.20 As such, site redevelopment has been guided over the years by details from Montgomery’s Anne novels to create and sustain the myth of place—in short, to satisfy reader expectations.

Meanwhile, tourism development was taking place outside the national park in Cavendish and area. By the mid-1950s, the number of cottage and cabin operators had grown to around 20, many adopting names that drew inspiration from Montgomery’s literary heritage. To name a few: Anne Shirley Cabins, Green Gables Bungalow Court, Shining Waters Lodge, and Avonlea Lodge (at this point operated by Katherine Wyand’s daughter). In addition, many restaurants and other businesses took names with the same inspiration as their drawing card for tourists.

With over one million visitors a year crowding into the national park by the early 1960s, it is no surprise that entrepreneurs were robust in developing attractions in the area to tap the tourist dollar. An early entry was Woodleigh Replicas, a collection of large-scale concrete and granite recreations of famous British landmarks created by Lt.- Col. Ernest Johnstone and opened to the public in 1957. An abundance of attractions would follow: Royal Atlantic Wax Museum (“Josephine Tussaud’s Wonderful World of Wax”); Pinehills Playland (with its haunted cave and gallery); King Tut’s Tomb and Treasures (where you could “Save yourself the cost of a trip to Egypt”); The Enchanted Castle (“To see your favourite storybook characters in action”); Atlantic Land (“An introduction to the Island’s way of life”); Marineland Aquarium; Rainbow Valley; Ripley’s Believe It or Not! and many more.

Green Gables Bungalow Court, 1960s. Designed and built in 1949–50 by Parks Canada, the 41-unit complex was intended to provide affordable family accommodations for park visitors but also serve as a model for private enterprise. Situated 200 yards from Green Gables, the bungalow court is now privately operated.

In the early 1970s, there were grumblings about what was perceived as the desecration of the purity and rural beauty of PEI. In a 1971 article titled: “Tourist Traps, Billboards, and a Plaster Kangaroo: How our Prettiest Province Could Become a Bargain Basement Disneyland,” author David Cobb cataloged a litany of attractions that were marring Canada’s “Garden of the Gulf,” establishments that were described as tasteless and out of place on the Island.21

By this time, the crossroads of Cavendish, immediately outside the national park, had become a busy intersection. As one visitor noted in 1972: “wax museum on one corner, modernized gas station on another, and stores, restaurants, and motels in all directions. I wish they had been in good taste, but nothing about their facades impressed me so much as their lack of taste and their dedication to dollars above all.”22

An April 2022 view of one of the cottages at Green Gables Bungalow Court. Almost all the tourist accommodation in the Cavendish area has prevailed as quaint mom-and-pop cottage camps, of which there are around two dozen in the immediate area. Photo by author.

A 1970s Kodachrome view of The Tower of London at Woodleigh Replicas. Initiated by Ernest Johnstone in 1945 and opened to the public in 1957, the attraction closed in 2008. Falling attendance due to changing tastes, along with the declining health of the last owner, were sighted as reasons for the closure.

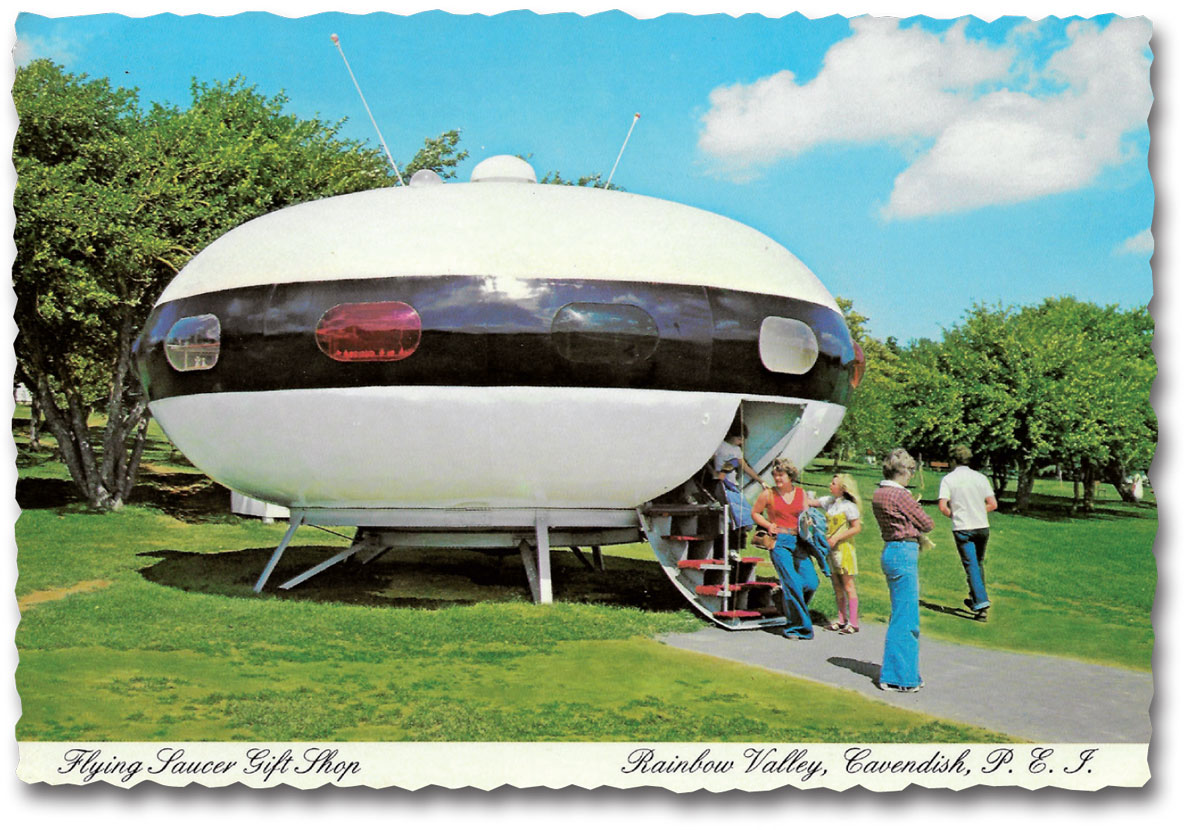

Flying Saucer Gift Shop at Rainbow Valley, 1970s. Among the attractions at the park was “Anne of Green Gables Land,” which featured large-scale reproductions of buildings that inspired Lucy Maud Montgomery. It did not seem to matter that the “real” Green Gables was a mere 10-minute walk from the park. Several attractions from the park, which closed in 2005, are now part of the nearby Shining Waters Family Fun Park.

That same year, an article in the Boston Globe was accurate in noting, “Many visitors first heard of the beauties of Prince Edward Island through Miss Montgomery, and her spirit is often invoked by those concerned about protecting them—from tourists among other menaces.” To paraphrase the rest of the article: Montgomery would be incensed with what parts of the island had become.23 Fifteen years later, a letter to the Charlottetown Guardian reiterated the concern more poignantly: “It is surprising Miss Montgomery’s headstone [situated in a cemetery at the main intersection in Cavendish] hasn’t become a whirling dervish from her turning over in her grave.”24 And on the commercialization would go—an evolving tourist imprint, seasonal in nature, impinging upon Montgomery’s Cavendish landscape.

Visiting Green Gables nowadays is a curious proposition. After navigating a capacious parking lot, you enter a visitor center that houses interpretative exhibits along with an extensive gift shop and café. Proceeding outside to the Green Gables site, recreated period farm buildings frame the farmhouse (the golf fairways have been pushed back and concealed behind a forest buffer). It is here where the boundary between fact and fiction, between real and imagined spaces, dissolves. So, while many visitors to the site have a deep appreciation for Montgomery’s life and work, as Alexander MacLeod points out, “the vast majority of people who come to Cavendish are attempting to visit the imaginary Avonlea and to put themselves, temporarily at least, into the same shared place where Anne once ‘lived’ in the real world.”25

In a sense, the experience of visiting Green Gables can be likened to a curated amusement, much akin to what can be found beyond the park boundaries in the sprawl of wax museums, amusement parks, castles, water parks, and the like. Commercialization co-exists outside and within the national park.

Anne of Green Gables scene (with Montgomery in the window) at the Royal Atlantic Wax Museum, c. 1960s. While this attraction is long gone, Wax World of the Stars carries on the wax museum tradition in Cavendish.

Aside from her birthplace in nearby New London, the foundations of the Macneill Homestead—where Montgomery was raised and penned Anne of Green Gables along with three other books—is hallowed ground. The site passed down to descendants of the family, and was cleaned up and restored in the mid-1980s. Placards with quotes and photographs have been placed around the area to interpret Montgomery’s life in what can only be described as an atmosphere of tranquility—somewhat removed from the commercial strip.

In 1936, shortly after the national park’s creation was announced (but before Green Gables was opened to the public), Montgomery wrote, “when I first penned Anne of Green Gables so many years ago, I had no idea what would spring from it all.” After initially being upset about the implications of a national park, she reconciled herself to it: “The premier [Thane A. Campbell] assured me that the woods and paths and dykes would be kept just as they were…. So, I began to feel that it was all for the best because those places will never be desecrated now. Still, there will be a good deal of change and I felt very, very sad my last night there.”26 Change, indeed—Montgomery had no idea.

Peter Glaser has contributed “Northern Roadsides,” a Canadian perspectives column, to the SCA Journal since 2008. This is his fourth feature.

Endnotes

2 S.L. Clemens (Mark Twain) quoted in a letter written by his secretary to Lucy Maud Montgomery, 3 October 1908, L.M. Montgomery Collection, University of Guelph.

3 Mary Henley Rubio, Lucy Maud Montgomery, The Gift of Wings (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2008), 2.

4 Montgomery, 1 August 1909, CJLMM, The PEI Years, 1901- 1911, 236. They also sought Montgomery, who lived on the Island until 1911. Following the release of Anne of Green Gables, Montgomery was inundated with fan mail. While much of it was kind and appreciative, she was also pestered with correspondence from tourists “holidaying on the Island who say they have read my book and want to ‘meet’ me. I dislike this kind of publicity and avoid it whenever possible. I don’t want to be ‘met.’” Montgomery to G.B. MacMillan, 31 August 1908, in My dear Mr. M.: Letters to G.B. MacMillan from L.M. Montgomery, eds., Francis W.P. Bolger and Elizabeth R. Epperly (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1980), 40.

5 The Gift of Wings, 286.

6 Montgomery, 4 August 1923, in Jen Rubio, ed., The CJLMM, The Ontario Years, 1922-1925 (Oakville, Ontario: Rock’s Mills Press, 2018), 167. Montgomery went on to note, “The Charlottetown [capital of PEI] people were especially indignant. They said it was the only “literary shrine” the province possessed, and it was a shame to destroy it.”

7 Alan MacEachern and Edward MacDonald, The Summer Trade: A History of tourism on Prince Edward Island (Montreal: Mc- Gill-Queen’s University Press, 2022), 70-71, 90; The Gift of Wings, 484-485. As one local noted, “I think the homes were almost compelled [to rent rooms to tourists] … because they wanted to stay in Cavendish.” Interview with Leita Andrew quoted in Diane Tye, “Multiple Meanings Called Cavendish: The Interaction of Tourism with Traditional Culture,” Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 29, no. 1 (1994): 123.

8 Montgomery, 17 September 1929, CJLMM, The Ontario Years, 1926-1929 (Oakville, Ontario: Rock’s Mills Press, 2019), 278.

9 Montgomery to G.B. MacMillan, 6 February 1928, 130.

10 Parks Canada, “The summer home of oil tycoon Alexander McDonald,” fact sheet, October 2013 (revised), http://parkscanadahistory. com/publications/dalvay/factsheet-e-2013.pdf, acc. 15 January 2023. The Parks Branch of the federal government has operated under various names since its inception in 1885. For simplicity, I refer to it as Parks Canada.

11 Williamson memo, 23 March 1936, RG84, vol. 1777, file PEI2, vol. 1, Library and Archives Canada (LAC), Ottawa, Ontario.

12 Undated newspaper clipping from Charlottetown’s The Guardian in Montgomery’s Unpublished Scrapbook, vol. 2., L.M. Montgomery Collection, University of Guelph, X25 MS A002.

13 Williamson to Commissioner James B. Harkin, undated [1936], RG84, vol. 1777, file PEI2, vol. 1, LAC.

14 Montgomery, 17 September 1936, in Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston, eds., The Selected Journals of L. M. Montgomery, Volume V: 1935-1942. (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2004), 93.

15 The Summer Trade, 90-91.

16 Ibid., 92-93.

17 As Diane Tye notes, “When the site for a national park was selected in 1936, the decision was tied more closely to tourism than to environmental protection.” Tye, “Multiple Meanings Called Cavendish,” 124.

18 Fred Horne, “Green Gables House Report,” Parks Canada Manuscript Report no. 352 (1979), 7.

19 Brenda R. Weber, “Confessions of a Kindred Spirit with an Academic Bent,” in Irene Gammel, ed., Making Avonlea: L.M. Montgomery and Popular Culture (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), 54.

20 Parks Canada, Green Gables Area Plan Concept (1981), 30.

21 David Cobb, “Tourist Traps, Billboards, and a Plaster Kangaroo: How our Prettiest Province Could Become a Bargain Basement Disneyland,” The Ottawa Citizen, 15 November 1971. 96-98.

22 A.B. Brooks, Letter to the Editor, Toronto Star Weekly, undated, 1972.

23 “There’s Nothing Flat About PEI,” Boston Globe, 17 September 1972, B-44.

24 “Tourism Overkill Feared at Anne’s Quaint Green Gables.” The Edmonton Journal, 15 August 1987, E-5.

25 Alexander MacLeod, “On the Road from Bright River: Shifting Social Space in Anne of Green Gables,” in Anne’s World: A New Century of Anne of Green Gables, eds., Irene Gammel and Benjamin Lefebvre (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 139.

26 Montgomery to G.B. MacMillan, 27 December 1936, 183.

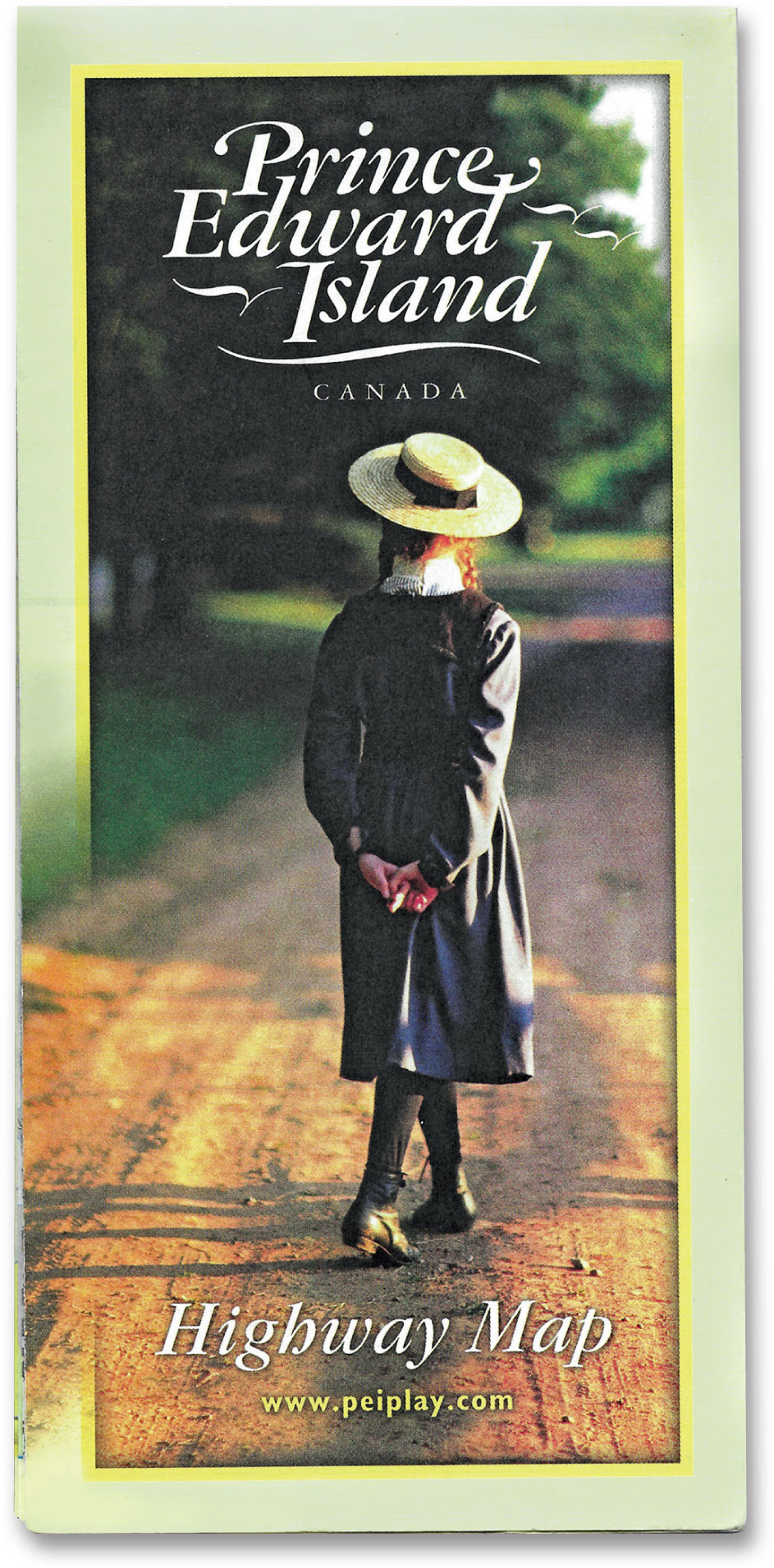

2003 PEI Highway Map. Anne of Green Gables and other images of “Anne” are trademarks of the Anne of Green Gables Licensing Authority Inc., which Heirs of L.M. Montgomery Inc. and the Province of Prince Edward Island own.

There’s more! To read the rest of this article, members are invited to log in. Not a member? We invite you to join. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2023, Vol. 41, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA