From coast to coast they’re springing up – Green Gable Camps

A typical Green Gable Cabin Camp, this one on U.S. 20 in Randolph, Nebraska.

Chroniclers of the evolution of hostelries along America’s highways all point to Alamo Plaza Courts as the first successful motel chain and, indeed, the only one of any consequence for at least several decades following the opening of its first location in Waco, Texas, in 1929. Reaching its fullest complement of 34 locations by 1960, the Alamo Plaza chain then began to decline as Holiday Inn and other newly emerging chains came to prominence following World War II.

Only a handful of other attempts at motel chains (other than referral chains and some loose tourist court associations) were made in the 1930s; those usually cited are “Pierce Pennant Terminals,” a would-be chain sponsored by the Pierce Petroleum Company; one hundred so-called “Autohavens” projected to be built within a radius of one hundred miles of Chicago; several plans for “highway hotels” along routes in California; and a few very small single-owner chains. Like Alamo Plaza Courts, most of these aimed at providing hotel-like accommodations on the roadside, which meant they necessarily entailed substantial financial investments. All fell far short of Alamo Plaza’s success, however, either failing to get off the drawing board or foundering after prototypes went up at one or a few locations.1

Roadsides scholar Warren Belasco identified the hefty problems confronting would-be chains in the 1930s: “Touring was still too seasonal in most of the country to support a heavily capitalized motor hotel that required year-round patronage to break even. Also, the tourist camp was not sufficiently standardized to warrant mass production; much experimentation remained to be done [regarding what tourists wanted]. . . . Finally, expensive motor hotels needed very affluent customers, yet wealthier non-campers were only beginning to come to the roadside.” Belasco concluded: “The depression brought many more to courts, but it also bankrupted potential chain investors. Big capital would have to await the return of prosperity after 1945, by which time the motor hotel concept would be well defined and nationally feasible. In the meantime, the profits and liabilities of this expanding but perilously insecure service industry would be left to Mama-Papa ‘amateurs.’”2

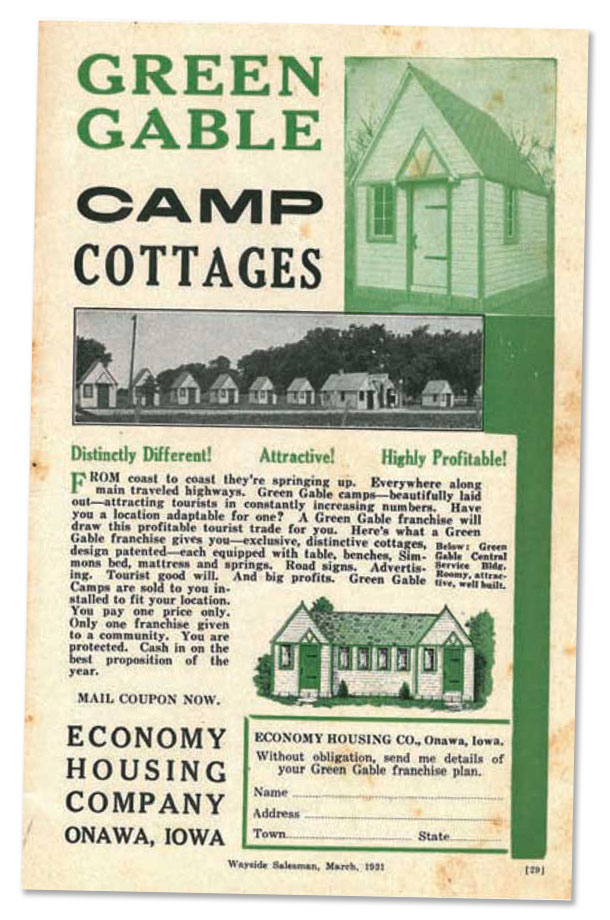

An early Green Gable ad from Wayside Salesman, March, 1931.

As it happened, however, out of this milieu of “Mama-Papa ‘amateurs’” in the early 1930s came another worthy attempt at a national chain called Green Gable Cabin Camps. Among motel historians, only John Margolies has taken note of this early entrant from the grass roots, but, uncovering little information about it, he concluded that it “failed to leave an indelible impression on the world.”3 True enough, Green Gable lasted only a few years as an aspiring national chain and was soon forgotten. During its brief time of active promotion, however, it made an impressive—even spectacular—start, which suggests that it had hit upon a successful formula for pushing rapid roadside expansion. Very early, Green Gable’s cabin camps far outnumbered the units in Alamo Plaza’s chain. Moreover, for the few years of its active phase, Green Gable pushed the growth of its chain more diligently and steadily than did Alamo Plaza and also adhered more strictly to the roadside marketing strategy of “place-product-packaging.”4 In these respects, at least, Green Gable came closer than Alamo Plaza did to the franchising practices that became commonplace after World War II.

That same March, 1931 issue of Wayside Salesman also had ads for cabins offered by two lumber companies.

In spite of the depressed national economy, the late 1920s and the very early 1930s were good years for tourist camp start-ups along America’s highways, which meant that there was also money to be made in the construction of tourist cabins. Some lumber companies and manufacturers of farm buildings soon took up the fabrication of tourist cabins as a profitable new sideline.5 Any of these companies, of course, stood to increase sales of their tourist cabins by promoting a chain of tourist camps, and by 1930, at least two of them, both located in Iowa, had taken that obvious next step.

About the Author: Lyell Henry is professor emeritus of political science at Mount Mercy University. He was the historian on projects of interpretation and/or restoration at three Lincoln Highway sites in Iowa and is now active in the reorganized Jefferson Highway Association.

There’s more! To read the rest of this article, members are invited to log in. Not a member? We invite you to join. This article originally appeared in theSCA Journal, Spring 2013, Vol. 31, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA