Gas, Food & Lodging

Fuel for Bertrand Goldberg’s Futuristic Architecture

A common criticism of roadside buildings is that, from an architectural perspective, they’re not impressive creations. That statement, however, is not always valid. Bertrand “Bud” Goldberg is a fascinating example of a famed architect who initially displayed considerable design talents in small-scale commercial structures.

Goldberg used early career successes, designing buildings used by motorists, as a stepping stone to more challenging architectural issues such as affordable housing, mixed-use urban development, and medical facilities. The Chicago-born architect attended Harvard, followed by the Bauhaus in Germany in the early 1930s. The latter institute harmonized the arts and integrated them within an architectural concept. “This omniscient view of ‘total building design’ nurtured Goldberg’s emerging outlook for combining efficiency, economy, and humane approaches to users’ needs for his architectural credo,” says James Logan Abell, a Phoenix architect. Goldberg subsequently returned to his hometown to study engineering at Armour Institute, now the Illinois Institute of Technology, and opened an architecture office at age 25 in 1937. Two early commissions were for the Clark Maple Gas Station and North Pole Ice Cream. Goldberg made filling your tank and satisfying your sweet tooth unforgettable experiences.

Goldberg used early career successes, designing buildings used by motorists, as a stepping stone to more challenging architectural issues such as affordable housing, mixed-use urban development, and medical facilities. The Chicago-born architect attended Harvard, followed by the Bauhaus in Germany in the early 1930s. The latter institute harmonized the arts and integrated them within an architectural concept. “This omniscient view of ‘total building design’ nurtured Goldberg’s emerging outlook for combining efficiency, economy, and humane approaches to users’ needs for his architectural credo,” says James Logan Abell, a Phoenix architect. Goldberg subsequently returned to his hometown to study engineering at Armour Institute, now the Illinois Institute of Technology, and opened an architecture office at age 25 in 1937. Two early commissions were for the Clark Maple Gas Station and North Pole Ice Cream. Goldberg made filling your tank and satisfying your sweet tooth unforgettable experiences.

The Chicago-born architect attended Harvard, followed by the Bauhaus in Germany in the early 1930s. The latter institute harmonized the arts and integrated them within an architectural concept. “This omniscient view of ‘total building design’ nurtured Goldberg’s emerging outlook for combining efficiency, economy, and humane approaches to users’ needs for his architectural credo,” says James Logan Abell, a Phoenix architect. Goldberg subsequently returned to his hometown to study engineering at Armour Institute, now the Illinois Institute of Technology, and opened an architecture office at age 25 in 1937. Two early commissions were for the Clark Maple Gas Station and North Pole Ice Cream. Goldberg made filling your tank and satisfying your sweet tooth unforgettable experiences.

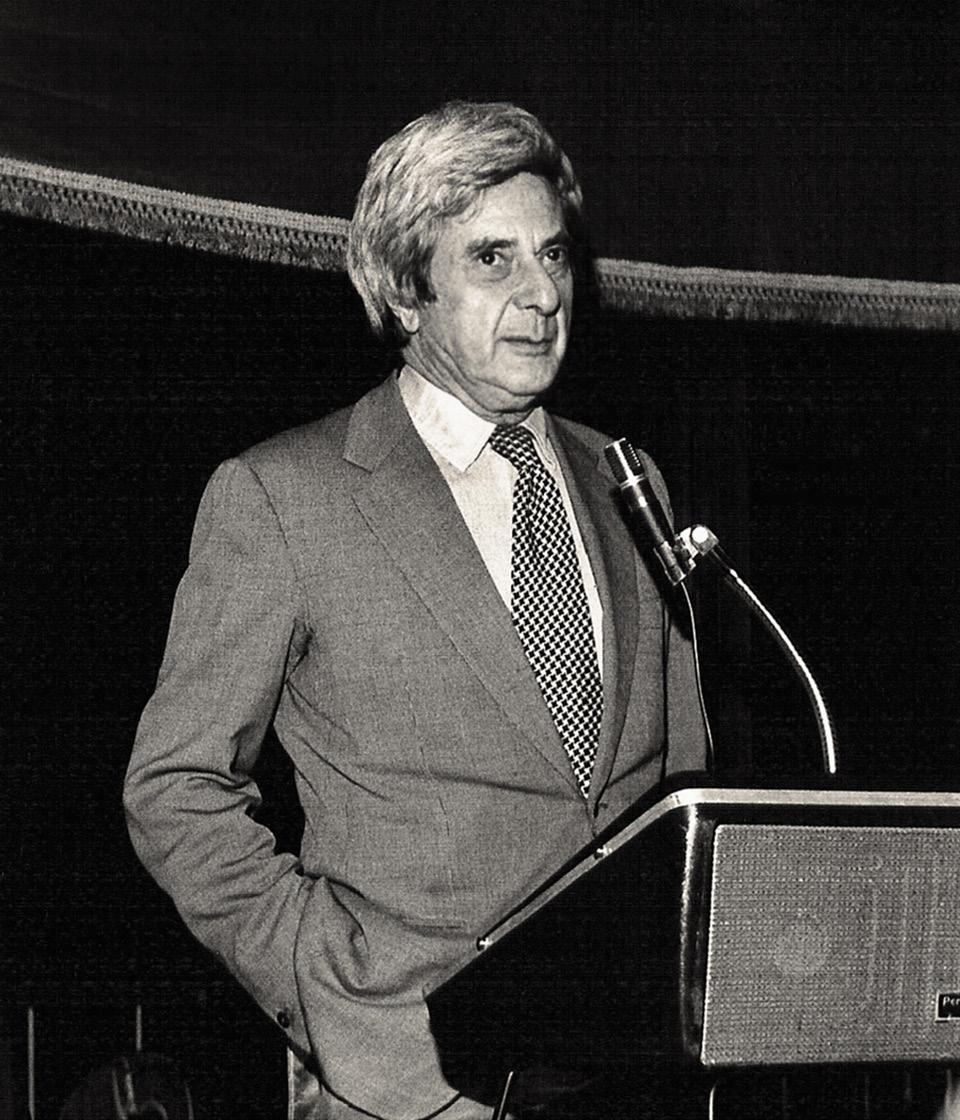

TOP and ABOVE: Clark Maple Gas Station in Chicago, 1938. Hedrich Blessing. INSET: Bertrand “Bud” Goldberg, 1970s. All images G. Goldberg + Associates unless noted.

The Clark Maple Gas Station was uniquely constructed in 1938 as a solution to demanding site conditions requiring minimal excavation. The two masts on which the roof hung were a simple answer inspired by Buckminster Fuller’s buildings for the 1933 Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago. Transparent walls exposed two washing-greasing bays, adding to the building’s appeal. Motorists flocked to this modern Chicago station. “It has shown that even Standard Oil could underestimate … what a new building like this could do for one of its gasoline dealers,” Goldberg told the Architectural Forum: “One of the notable features of the gas station were the neon lights spelling, ‘Gas For Less’ woven into the cable supports from the masts,” says his son, Geoff Goldberg. “My father told me that the neon signage at the gas station ‘looked lovely, and lasted about one night, as the winds broke the neon.’”

North Pole Ice Cream in River Forest, IL, 1938. Hedrich Blessing.

That same year, Goldberg designed another futuristic commercial building, North Pole Ice Cream, in the Chicago suburb of River Forest. The architect created it as a portable store that could move north and south, like migrating birds, to sell ice cream in season. “Its glass walls and cantilevered roof were suspended from a mast anchored to a truck chassis, a part of the building,” according to www.bertrandgoldberg.com. The architect envisioned a fleet of these stores served by a “mother truck“ that manufactured ice cream.

Geoff says his parents were interested in mobility, speed, and flexibility and their related architectural aspects, be it diners, roadside foods, or ideas about flexibility and convenience. “These were all part of the modern world and were embraced as part of our thinking. My father was interested in how things were used and made, but also in the role of time, the making, and the day-to-day experience of architecture. For example, he was interested in autos and designed a rear-engine one in 1938.” Another industrial focus of Goldberg’s was prefabrication. It was found in his housing work from 1938, where Goldberg used prefabricated wood panels and designed the factory that produced them. Also, in 1946 with a prefabricated bathroom which Frank Lloyd Wright used in one of his houses and then in the plywood boxcars of the early 1950s.

Goldberg’s rendering of the Route 66 Motel in Chicago, 1958.

Twenty years later, the Route 66 Motel was an unbuilt project for a site on Chicago’s South Shore Drive, which previewed two round towers of differing heights. Goldberg would later reprise this 1958 design feature on a much grander scale.

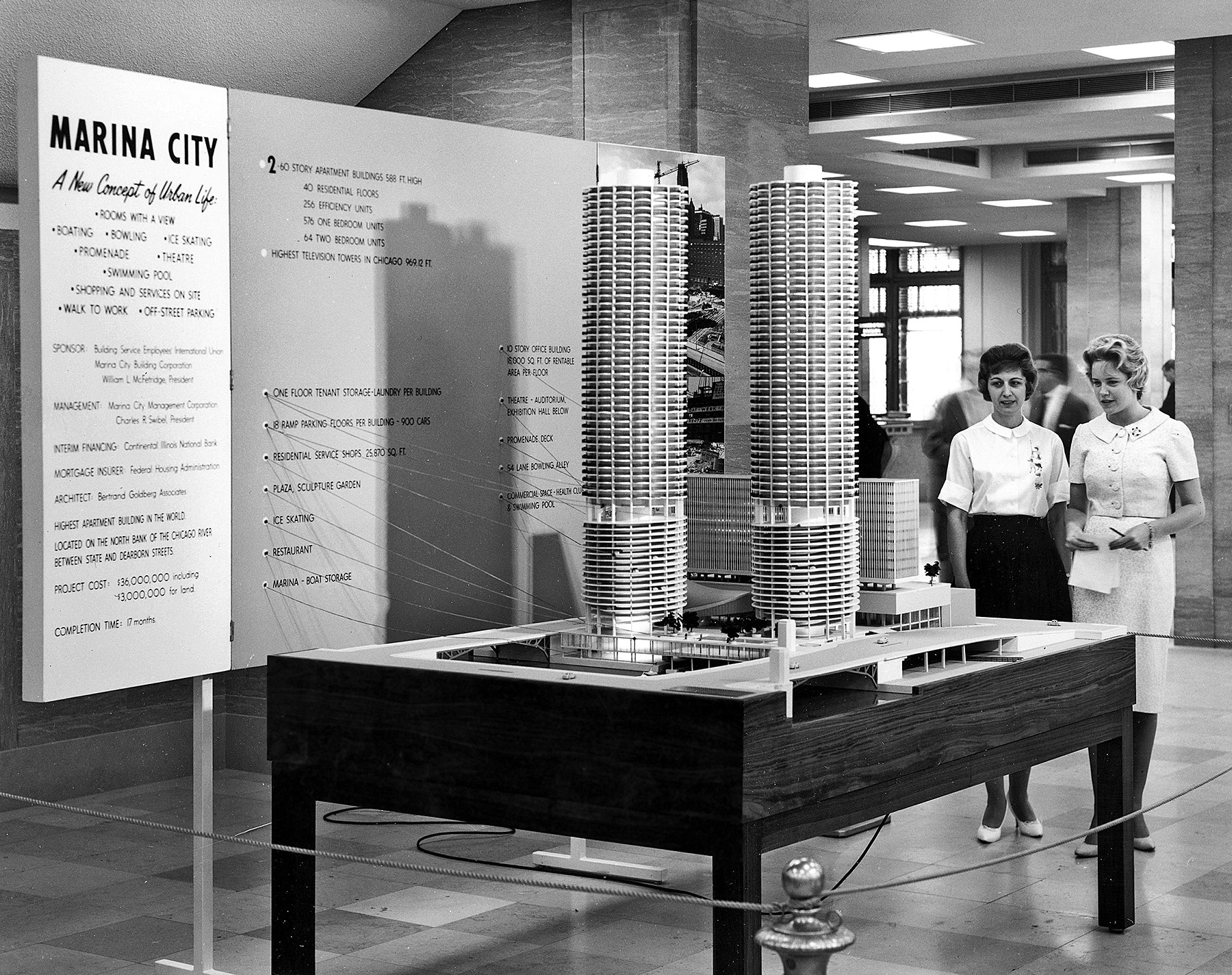

Photograph and model of Goldberg’s Marina City in Chicago, mid-1960s.

Goldberg honed his talents from these commercial structures to create his seminal work, the twin towers of Marina City in Chicago, in the mid-1960s. The 62-story residential concrete towers anchored a theater, rail line, ice-skating rink, bowling alley, and office building. The spiral ramps on the first 20 floors of the towers show the parked vehicles rather than hiding them—an unusual approach. More than a century later, the development remains a highly desirable address.

A proposed complex and hospital tower of Good Samaritan Hospital, Phoenix, 1982.

The Chicago architect would later adopt aspects of the Marina City design for other projects, including medical facilities like Good Samaritan Hospital in Phoenix. The hospital’s concrete towers were how I first became aware of Goldberg’s work from an article by local architect James Logan Abell. He, along with Rusty McCaleb and others, aided Goldberg in its creation in the early 1980s. Goldberg also partnered with Herman Chanen, a prominent Phoenix contractor, in proposing a much larger development near the hospital for housing, offices, and the healthcare-related industry, of which only the office building was built.

Pat Casler (blue top) and Geoff Goldberg (tan shirt) at the Englewood Diner in Dorchester, MA, during the All-Night, All-Night Diner Tour, 1980.

Besides Goldberg’s early forays into small-scale commercial buildings, the architect’s family has another serendipitous SCA connection. Like father, like son, Geoff has his own successful architectural firm in Chicago, G. Goldberg + Associates, and was an early member of the SCA. “A friend and I used a diner to analyze HVAC systems in architecture school,” Geoff recalls. “Heat was generated at the cooktop, and cooling was achieved through flow-through ventilation. The professor was less than enthusiastic, but the class loved it.”

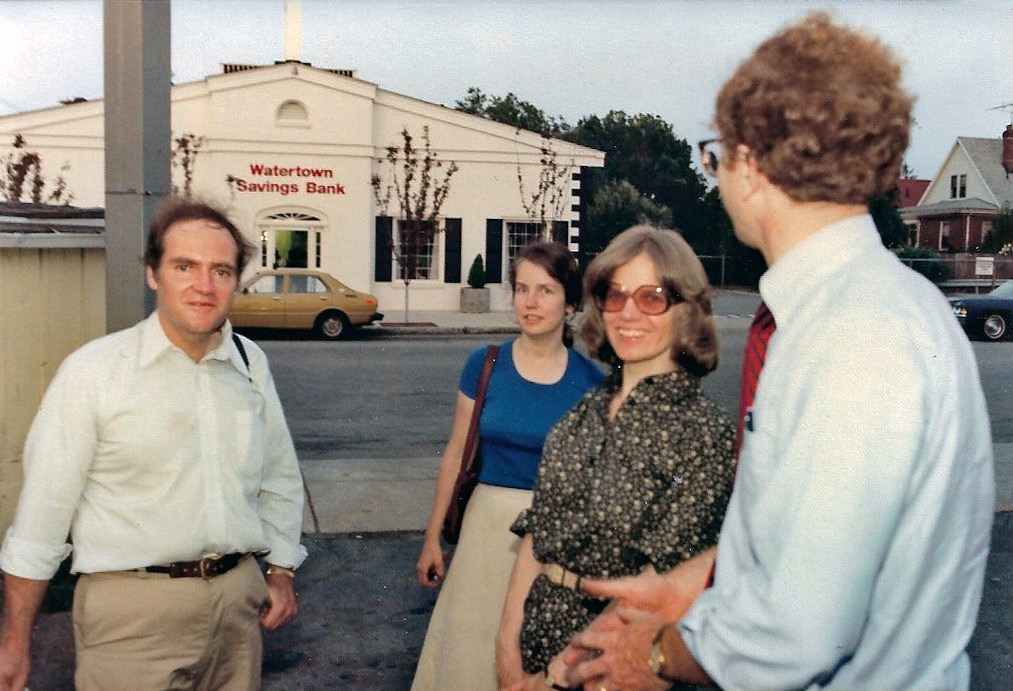

From left, Chester Liebs, Pat Casler, Susan Maycock, and Charlie Sullivan before the 1980 All-Night tour. Both photos by Jim Peter.

Geoff fondly recalls our organization, especially attending the All-Night, All-Night Diner Tour in Massachusetts and Rhode Island in 1980 with SCA founder Chester Liebs and friends Pat Casler and Jim Peter. Geoff has hazy recollections of the long-ago event, but Peter commented, “My memory of the event is the strange sense of adventure amidst a small group of folks who cared about this sort of stuff at that time.”

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2023, Vol. 41, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA