By Chris Berger

All photos by the author unless otherwise noted

It’s a clear spring morning at Warm Mineral Springs on Florida’s Gulf Coast and sweat is collecting at my hairline as I stand outside the shuttered Cyclorama, a windowless concrete block structure shaped like a giant tuna can.

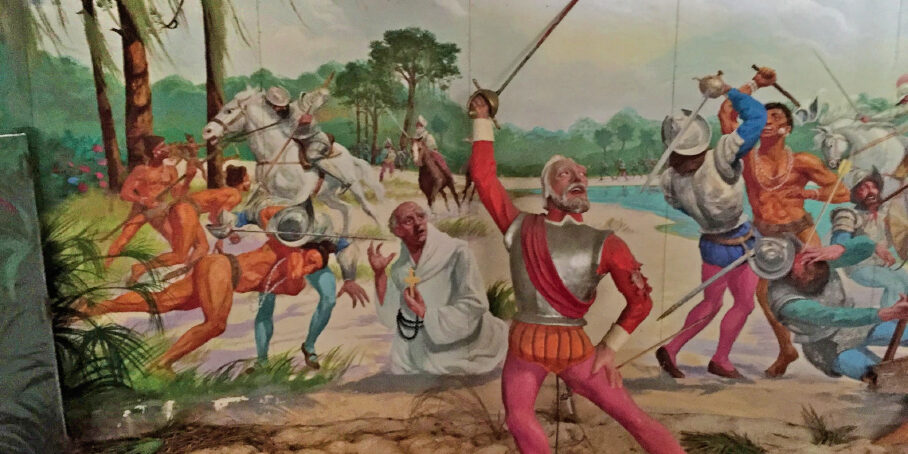

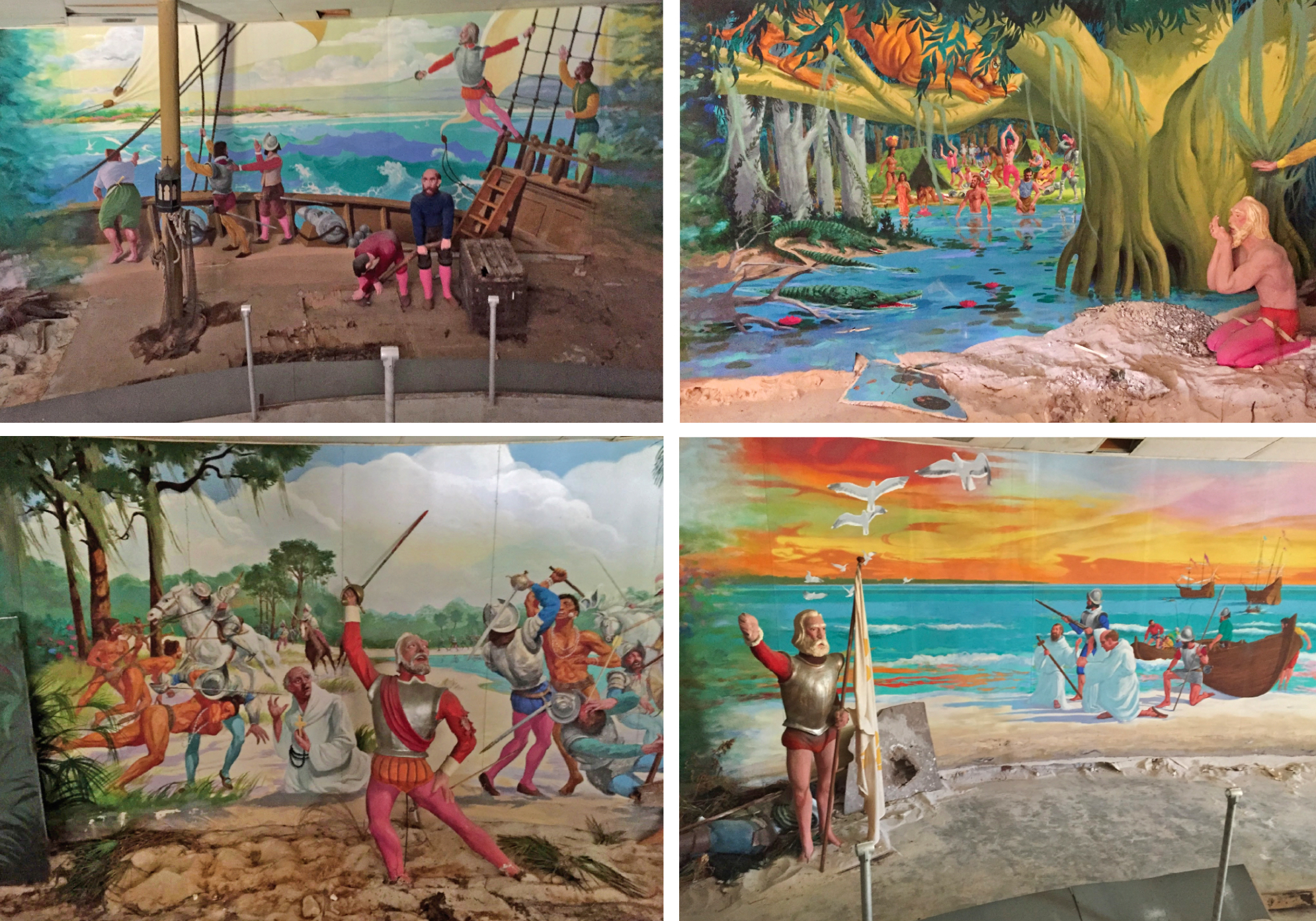

1: Ponce and his crew spot the Florida coast in 1513. 2: Ponce and his men meet with the Calusas. 3: The Spaniards and Calusa battle in 1513. 4: In 1521, Ponce lands at Charlotte Harbor, near Warm Mineral Springs.

1: Ponce and his crew spot the Florida coast in 1513. 2: Ponce and his men meet with the Calusas. 3: The Spaniards and Calusa battle in 1513. 4: In 1521, Ponce lands at Charlotte Harbor, near Warm Mineral Springs.

The Cyclorama was built in 1959 to house an exhibit that depicted Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de Leon’s rumored quest for the Fountain of Youth, the mythical waters that provide eternal life to those who drink from it. It closed about 15 years ago, and few people have ventured inside since.

With many turnovers in ownership and management in recent years at Warm Mineral Springs, a spa and recreational venue, the Cyclorama’s condition is a concern for preservationists. Florida’s climate and critters are not kind to artwork, and I prepare for the worst as my host struggles to locate the correct key to the door among the dozens on the ring. A few hundred feet away, dozens of bathers—almost all of them seniors of Eastern European descent—frolic in the constant 80-something degree water of the 250-foot-wide teardrop-shaped pool, billed as the largest mineral spring on the planet.

The legend is that Warm Mineral Springs was Ponce’s object of desire when a Calusa Indian’s arrow mortally wounded him in 1521 at San Carlos Bay, about 50 miles south of here. Today Warm Mineral Springs is among at least five springs in Florida that claim to be Ponce’s Fountain of Youth.1

But there is no record that Ponce even believed in the Fountain of Youth fable much less pursued it. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés appears to have concocted the story for his book on the Spanish colonies published in 1535—14 years after Ponce died.2 Ponce, Oviedo wrote, was seeking the Fountain of Youth to cure impotence.3 Oviedo was not exactly an impartial source; he was allied with Ponce’s rival Diego Columbus, the son of explorer Christopher.4 Nonetheless, Oviedo’s tongue-wagging tale was echoed by later writers, notably Washington Irving.5

“The Fountain of Youth has become a cliché in our popular culture, a story repeated again and again in film and television from Disney’s 1953 animated film Don’s Fountain of Youth to the movie Cocoon,” said Rick Kilby, author of Finding the Fountain of Youth: Ponce de León and Florida’s Magical Waters. “The connection of Florida to Ponce de Leon’s mythical quest appears to be linked for eternity.”6

A concrete tiered walkway system and the audio room are located in the center of the Cyclorama.

There’s more! To read the rest of this article, members are invited to log in. Not a member? We invite you to join. This article originally appeared in theSCA Journal, Spring 2018, Vol. 36, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA