Harnessing Buffalo

By Diane DeBlois

Buffalo did not roam in Buffalo, New York—that’s almost certain. These ungulates did wander pretty far east from the Great Plains after the drought of 1600, but probably did not see Niagara Falls. Buffalo’s name actually came from the creek where it was founded as a trading community in 1789. The creek, which appeared on maps in 1759, had been named for a Seneca Indian who lived by its banks. What physical or personality traits linked this Indian to the shaggy bovine were not recorded.

Top: Engraving of a locomotive racing a buffalo on the Great Plains, from an 1873 stock certifcate for the Peoria & Bureau Valley Railroad Company. Above: A 1901 $10 bill, designed by Raymond Ostrander Smith with buffalo image by Charles R. Knight.

The image-makers of Buffalo didn’t let natural history interfere with excellent branding potential, particularly for the Pan American Exposition of 1901. The event, designed to foster trade relations among the Americas, also marked the centenary of Buffalo as a planned city.

Fig 1: Label for 1938 National Airmail Week celebrated by the Bison Philatelic Society. Fig 2: A letter carried by a herd of Buffalo stamps to China in 1936.

The iconic buffalo image widely used during the exposition probably began with a drawing by Charles R. Knight, a New York wildlife artist, whose model resided at the Zoological Park in Washington. The drawing was chosen for a special $10 bill produced by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing for the 1901 fair and re-used by the same agency for a 30¢ postage stamp in 1922. The basic design of this postage stamp was in turn pirated in 1938 for use by a Buffalo philatelic group.

Illustrated envelope of the Buffalo Steam Roller Company, used in 1910

Fig 1: Letterhead for the Buffalo Fertilizer Company that was used in 1907. Fig 2: Illustrated envelope of the Buffalo Steam Roller Company, used in 1910.

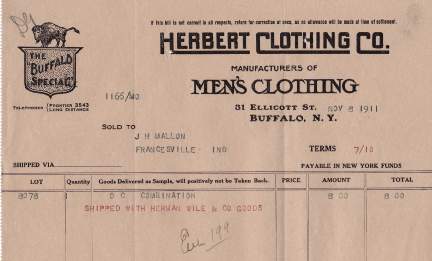

This figure of the lone buffalo bull soon competed for trademark recognition among Buffalo businesses. The Buffalo Steam Roller Company’s bison is similar to the $10 bill while the Buffalo Bank Note Company merely reversed his stance. For the Buffalo Fertilizer Company, the tail is a little less arched. More subtle was the “Buffalo Special” of the Herbert Clothing Company, but bolder was a later incarnation for the Buffalo Insurance Company.

Billhead of the Herbert Clothing Co., 1911.

For the 1901 fair, the exposition committee initially used a Buffalo demurely posed atop a globe for tickets and other promotional materials, but then switched to a thundering bull, which was much copied and then itself celebrated 100 years later with a commemorative U.S. Postal Service stamp in 2001.

For the 1901 fair, the exposition committee initially used a Buffalo demurely posed atop a globe for tickets and other promotional materials, but then switched to a thundering bull, which was much copied and then itself celebrated 100 years later with a commemorative U.S. Postal Service stamp in 2001.

Fig 1: Illustrated envelope of the Buffalo Insurance Company, used in 1930. Fig 2: Chromolithographed envelope, copyright G. H. Dunston, published by the Raynor Hubbell Stamp Company and overprinted for the Buffalo dry goods store, the William Hengerer Company.

The most intriguing buffalo-related image at the exposition however, involved the Singer Sewing Machine Company, which had been manufacturing in Buffalo since the 1860s. The company made a large investment in the fair in the form of exhibits and a wide range of colorful advertisements, including a 50-piece jigsaw puzzle accurately picturing a Singer delivery wagon— except that it is pulled by harnessed buffalo! Could this stunt have been performed at the fair?

Fig 1: Promotional label for the Pan American Exposition used on an envelope mailed within Pavilion, New York, a town near Buffalo, in 1901. Fig 2: Illustrated envelope for the American Buffalo Robe Company, used in 1902.

It’s not impossible. Collectors of photo postcards might be familiar with Clyde Jones and his team of buffalo hitched to a wagon. In his book, Some of My Yesterdays, Earl W. Schwenk recalls as a 14-year-old attending a rodeo to celebrate the opening of a bridge over the Missouri River in Chamberlain, South Dakota, in 1925:

I remember very vividly a team of buffalo that was hitched to a two-wheeled cart, built just like a chariot like they drove in the Roman days. This team was trained when they were young, and they were driven just like a team of oxen, with a yoke. They were owned by Clyde Jones, who was from the western part of the state, out in the Black Hills area from Rapid City and he had been a former rodeo bronco buster and was very good at this sort of thing. He had lots of patience, apparently, for training a team of buffalo to drive. And they were in the parade.

While the exposition’s Pan American Midway boasted many over-the-top exhibitions such as visiting a topsy-turvy “House Upside Down” or traveling to the moon on the “Luna” airship, the Singer delivery wagon powered by a team of buffalo is certainly within the realm of possibility.

Below: Advertising jigsaw puzzle distributed by the Singer Sewing Machine Company at the Pan American Exposition, 1901.

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2011, Vol. 29, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA