San Fernando Valley at Midcentury

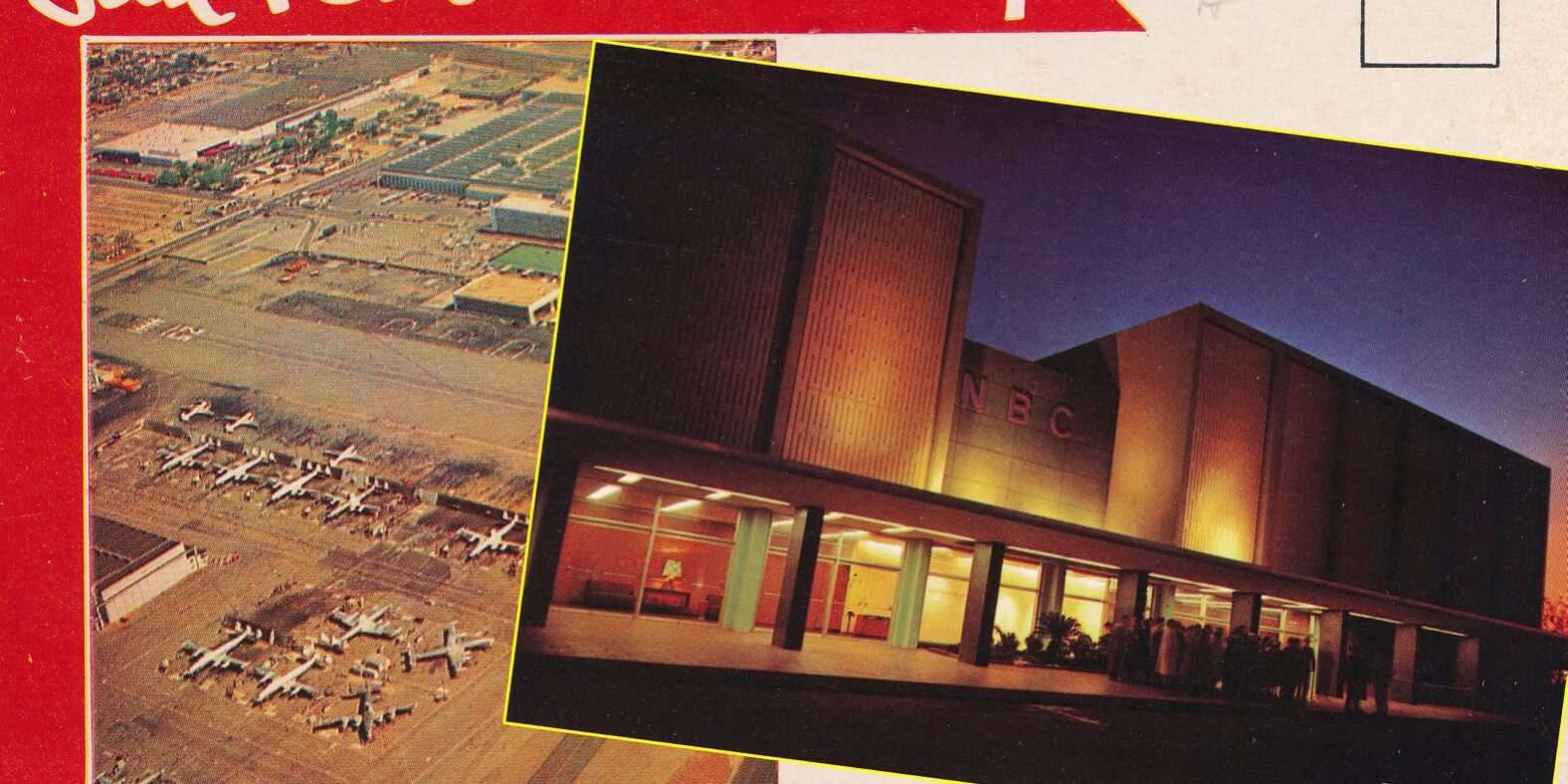

BEAUTIFUL DOWNTOWN BURBANK.

Non-California’s introduction to the Los Angeles Basin’s San Fernando Valley came with the 1968 inauguration of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In broadcast from “beautiful downtown Burbank” at the Color City television studio opened there in 1952. The original comment was sarcastic like the opposite was true, but it was repeated by others as if it wasn’t sarcastic. It was the perfect metaphor for the 20th century Modernism that attached itself to America’s suburbs, especially in southern California. Modernism was the contradictory visual signature for the progress and prosperity promised by the American Way, as well as the materialism and blight heralding the collapse of Western civilization, no place more so than the Valley.

WHAT’S BEHIND THE HOLLYWOOD SIGN?

Hollywood’s icon sign was built in 1923 to advertise the Hollywoodland housing development being cut into the Santa Monica Mountains. When the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce took control of the sign in 1947, they demo-ed the “Land.” This high-angled shot shows what’s behind the sign, the San Fernando Valley, the farmland “hand” on the north side of the Santa Monica Mountains that once fed Los Angeles.

WHEN RAILS RULED THE VALLEY.

The transformation of the Valley began in 1913 when water from the Los Angeles Aqueduct first tumbled down the Cascades and into the San Fernando Reservoir. To get access to the water, farmer-residents of the Valley had to agree to annexation by the City of Los Angeles. Rather than the automobile, initial development was more dependent on the Southern Pacific Railroad and Pacific Electric interurban network which came into the Valley up the Los Angeles River from Los Angeles and over Cahuenga Pass from Hollywood.

RED CARS TO THE ALEX.

The Pacific Electric “red cars” entered the Valley in 1904 stimulating growth in Glendale, Burbank and along the San Fernando Road, which became US 99, the original automobile spine of California. This 1958-ish view north up Brand Boulevard through downtown Glendale shows the Sputnik-topped, neon-trimmed tower to the Alex Theater. Opened in the Egyptian Revival style in 1925, the tower went up in 1942 to modernize the entrance to the theater’s forecourt. The Alex has been saved and restored as a performing arts center.

FREEWAY RUNNING THROUGH THE YARD.

First, water poured into the San Fernando Valley from the north and then cars poured into the Valley from the south. When the original section of the Hollywood Freeway opened over the Santa Monica Mountains in 1940 it shared Cahuenga Pass with the Pacific Electric red cars. The freeway was extended south to Los Angeles by 1954 and north through the Valley to the Golden State Freeway by 1968. By the time this postcard was snapped around 1958, the PE tracks were buried by ten lanes of freeway.

Car Culture. The Valley boomed in the Postwar years, simultaneous to the automobile-culture that scattered car washes, dealerships, coffee shops, drive-in restaurants, and garage-pierced houses all over the Valley.

MOTEL STRIP.

San Fernando Road was the Valley’s original Motel Row. Part of US 99, San Fernando Road connected Los Angeles with the Central Valley and all points North. More and larger motels proliferated when the route was paralleled by the Golden State Freeway (I-5) in the 1950s.

VALLEY MODERNISM.

Valley population went from 150,000in 1940 to 850,000 twenty years later. In the 1950s, the Valley was new and new was Modern. International Style office buildings went up in Glendale, Burbank and Encino. A spiral staircase swept to the second floor of the mostly-glass Boulevard Building, and the 1959 Glendale Federal Savings Building announced its name on a towering pylon slab. Visual fronts and pylon signs would also be the hallmark of the Valley’s ultra-Modern commercial roadside.

BROAD STREETS AND BIG SIGNS.

This postcard captured a 1950s Van Nuys Boulevard after the Pacific Electric tracks had been paved over. Valley business streets were wide and fast and bordered by low-profile buildings that had to rely on signage that was bold and bright day and night.

QUAINT, OLD-FASHIONED AUTO STRIPS.

Though auto-oriented and neon-lit, the first Valley commercial boulevards to develop (the ones closest to downtown Los Angeles) followed the older taxpayer model of putting businesses against the sidewalk. Businesses fronted by massive parking lots would come later. Studio City Theater opened on Ventura Boulevard in 1938, not far from where Hollywood spilled over Cahuenga Pass into North Hollywood.

MODERN MEETS NEON.

Modernism’s ideological rejection of ornamentation as superfluous was reinforced in environments built by and for the automobile. Neon signs had to announce businesses to fast-moving motorists well before that which could be done by a Corinthian column capital. The building itself, however, could incorporate certain eye-catching cants and slants that were functionally appropriate to the environment and therefore presented the business as Modern, like Burbank’s Bel Air Palms Motel on Olive Avenue.

BOB’S BIG BOY. Drive-in hamburger joints spread along San Fernando Valley boulevards in the 1930s. Bob Wian opened the first Big Boy at 900 E. Colorado Avenue in Glendale in 1936. The restaurant was more sign than building by the time this image was shot in 1949. The Glendale Bob’s where it all began served its last Big Boy in 1989.

PYLON PARADISE IN THE VALLEY’S RESTAURANT ROW.

Bob’s Big Boy changed with the times, joining Southern California’s postwar coffee shop craze that stretched the bounds of ultra-Modern roadside commercial architecture to the stratosphere. The 1949 Bob’s Big Boy built on Burbank’s Riverside Drive announced its low-profile presence with a massive pylon sign that continues to do its job at a place where you can still get the original double deck hamburger.

CALIFORNIA COFFEE SHOP.

Googie’s in Hollywood, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright-trained John Lautner in 1949, crossed Ultra-Modernism with a coffee shop and created a California original that swept the nation by way of the San Fernando Valley. Modernism was never more flamboyantly expressed than with crazy canted roofs seemingly supported by glass visual fronts announced by a giant neon sign. Sidney Hoedemaker opened several Hody’s coffee shops after 1948 including this one on Lankershim Boulevard in North Hollywood.

WEST COAST DINER.

Wide open and filled with natural light; cantilevered counter stools and terrazzo floors; a Wrightian mix of manmade materials and natural wood and stone; cocktails at night and breakfast all day; the California coffee shop was a more Modern West Coast version of the old diner found in eastern cities, and subsequently influenced diner design. Page’s operated on Roscoe Boulevard in Northridge.

COFFEE DAN AND BIFF.

Coffee Dan’s in Van Nuys used an A-frame design later adopted by the International House of Pancakes. Biff’s, named after drive-in operator Tiny Naylor’s son, had a canted visual front, structural bents and a pylon sign. The Valley Biff’s operated at Lankershim and Magnolia in North Hollywood. Southern California architects like Wayne McAllister and especially Armet and Davis came to specialize in ultra-Modern coffee shop design.

DIMMING DOWN MODERNISM.

Modernism reigned into the 1970s, but it wasn’t the same. Wood, brick and stone started to crowd the glass visual fronts, plastic backlit signs began to replace neon, and everything was carpeted. Interior spaces were sumptuously -even garishly- upholstered in reds and purples, blues and yellows, and orange and greens surrounded by paneling and chandeliers that hid from the natural light of day. Otto Nassar opened the Pink Pig on Van Nuys Boulevard as a fine-dining establishment around 1949 catering to celebrity types living in North Hollywood. The Star Trek chairs and Liberace-like piano bar were added sometime in the late-1960s. Having spanned the entire Postwar period as a Valley institution, the Pink Pig closed in 1979.

SPRAWLING SHOPPING CENTERS AND TOWERING TOWERS.

North Hollywood’s Valley Plaza opened at Victory and Laurel Canyon boulevards as one of the first shopping centers in the Valley in 1951. The Valley Plaza Tower went up as the tallest building in the Valley in 1960. In 1976, the International Style skyscraper was sporting a full-length Bicentennial mural. The Bicentennial was the end of Modernism as we knew it. The San Fernando Valley was filling up, but suburbia was already shifting into the adjacent Simi Valley.

BEAUTIFUL DOWNTOWN BURBANK BEFORE.

The energy and optimism of the postwar Valley was captured in this postcard 1958 view of San Fernando Boulevard in downtown Burbank.

BEAUTIFUL DOWNTOWN BURBANK AFTER.

Modernism, like the ever-expanding commercial roadside, is self-consuming. When the bloom started to fall from Burbank, the town attempted a pedestrian mall remodel that blocked San Fernando Boulevard from Tujunga to San Jose, from 1967 to 1989. It didn’t work, and the road was reopened all for one block encased in a shopping mall.

I THINK I’VE BEEN HERE BEFORE.

Frank Zappa called the San Fernando Valley “a most depressing place” when he made fun of it with his daughter Moon in the 1982 song, “Valley Girl.” But when the movie soon followed it was “Beautiful Downtown Burbank” all over again, blurring the line between sarcasm and celebration. Even when locals run down their hometown it’s still their hometown, and the Valley looks a lot like home to many suburban Americans. Hollywood studios -Warner Brothers, Universal, Disney- were in the Valley right from the beginning and have been shooting it as a cheap and easy quintessential America for decades. We were there when the Brady Bunch lived on Dilling Street in Studio City. We saw E.T. phone home from Porter Ranch. We were at the Sherman Oaks Galleria when Mark Ratner was the assistant to the assistant manager at the movie theater. We watched the Terminator buy guns in Van Nuys. We even knew, regardless of how many times they used the word ‘Scranton,’ that Dunder Mifflin was somewhere in the Valley. Love it or hate it … love it AND hate it, the Valley is home.