CAVES & CARS ON MISSOURI’S ROUTE 66

The limestones of the Missouri Ozarks are pock marked with show caves that prospered on the traffic of Route 66.

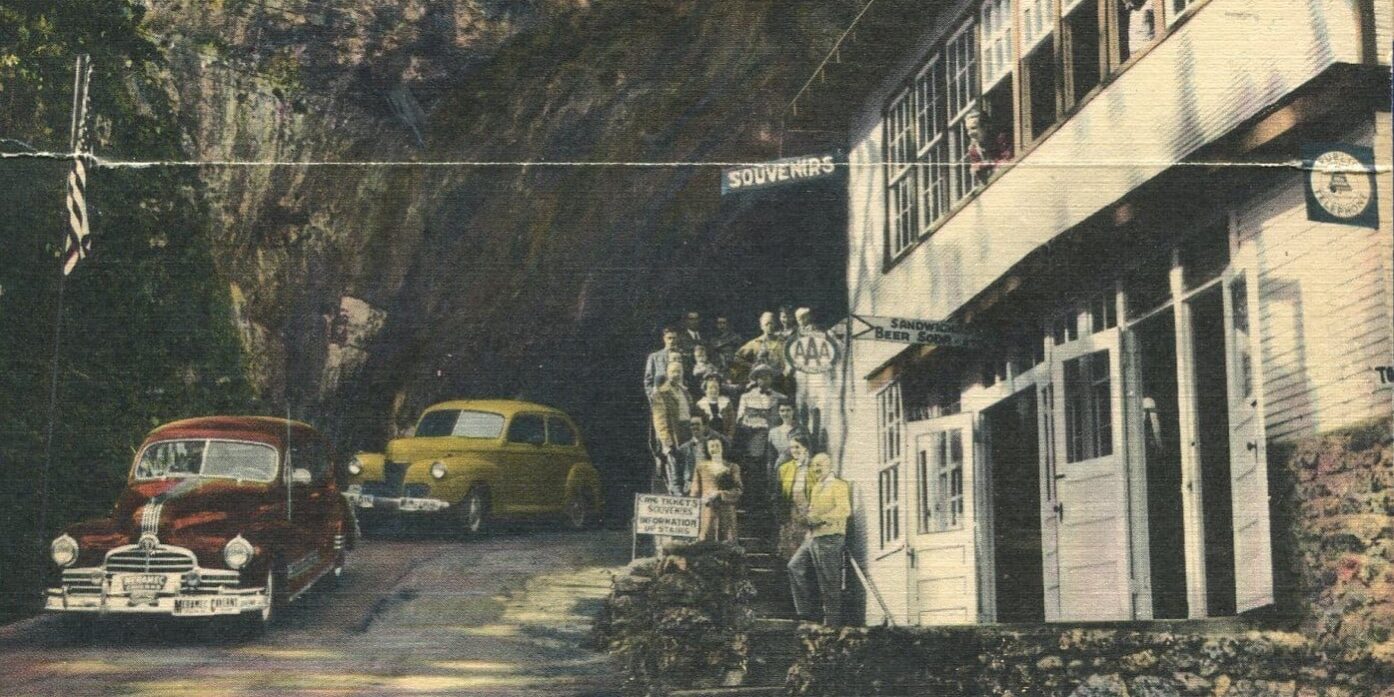

Although known since the 18th century, Meramec Caverns’ fame was directly linked to nearby US 66, motorists from which arrived as soon as Lester Dill opened it as the world’s only drive-in cave in 1935.

The well-advertised novelty of parking inside a cave was part of the appeal of Meramec Caverns that also suggested its great size.

Marked out between Chicago and Los Angeles in 1926, US 66, the Mother Road, angled across the Ozarks carrying a ceaseless torrent of cars past the entrance roads to Meramec and nearby Onondaga caverns. Both caves were an easy day trip from St. Louis.

Lester Dill made sure Meramec Caverns was well-advertised up and down US 66 as in the case of this barn painting east of Springfield that advertises across old Route 66 to traffic on paralleling I-44.

The Meramec Caverns entrance road turned off US 66 and crossed the paralleling St. Louis & San Francisco -the Frisco- which carried the first out-of-town tourists to Ozark show caves long before the automobile.

Even Meramec Cavern’s massive maw could not accommodate the cars of all the tourists who wanted to see what was inside the most famous cave on Route 66.

In this 1930s postcard, the Big Piney River dissects the Ozark Plateau revealing Ordovician-aged Gasconade dolomite (like limestone but with more magnesium) capped by Roubidoux sandstone. The Cambrian Eminence dolomite of Meramec and Onondaga caverns lies beneath the Gasconade and outcrops in the river valleys to the northeast. Layered, easily split and readily available along the length of US 66 from St. Louis to Springfield, this stratum was the raw material for dozens of Ozark rock masonry businesses like the Devils Elbow Café

“Giraffe rock” was a favorite facing technique for Route 66 roadside architecture in the Missouri Ozarks from the 1920s through the 1950s. Sandstone slabs in varying shades of yellow were set in Portland cement with limestone and dolomite to create an eye-catching, polychromatic veneer over modest framed buildings. Arthur Nelson built his Dream Village in 1934, two years before his death.

Route 66 grew with the traffic streaming between the Midwest and the Southwest. Most of its length from St. Louis to Springfield was dualled and divided by 1955, and then replaced after the passing of the Interstate & Defense Highway Act of 1956. Throughout the 1960s, traffic shunted back and forth between old pieces of US 66 and newly opened sections of I-44. Although devastating for roadside businesses on old 66, show caves required only new billboards visible from the interstate to tap into the relocated river of tourists.

The surprising amount of early show cave advertising that went into boasting about parking was a way of declaring the cave to be easily accessible, modern and popular. Parking for 10,000 automobiles at Meramec Caverns, albeit not in the cave, suggests a need for 10,000 parking spaces that only a world-class, must-see attraction could fill.

Meramec Caverns gained a new customer base with the nearby opening of Fort Leonard Wood in 1940. This postcard of Cold War era servicemen in the Jesse James section re-imagines the cave’s commodious interior as the world’s safest atomic shelter.

The first tourists to the newly christened Onondaga Cave boarded Frisco excursion trains from the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Like nearby Meramec Caverns, the show cave thrived with the arrival of Route 66 and in 1949 was purchased by Meramec impresario Lester Dill.

The Cave Café at Onondaga was made from the same Eminence dolomite that encased the cave.

Plenty of parking at Leasburg, Missouri’s Onondaga Cave.

Once it was discovered that Onondaga Cave extended beneath an adjacent property what was once called the Mammoth Cave of Missouri became the focus of a cave war with the show cave being split by a fence right through its main passage. Half the cave operated as Onondaga and the other half as Missouri Caverns. This 1930s brochure warns motorists bound for Onondaga not to be duped into going to the “other” cave, which appeared first on the only road off US 66 to serve both operations.