It was the first brand created by advertising. The first promoted by a multimillion-dollar media campaign.1 And perhaps one of the main reasons why the dates on nearly all Buffalo nickels are worn smooth.

Uneeda Biscuit was the first product of the National Biscuit Company (NBC, now Nabisco). And working with the country’s first national advertising agency, NBC had thousands of monumental Uneeda-branded brick-face signs painted on buildings across the country. If you live in any region that was an industrial or commercial center at the beginning of the twentieth century, you are likely just a few minutes’ drive from a survivor, or several. But beware, as I can personally attest, Uneeda Biscuit can be a gateway drug to a serious ghost sign addiction.

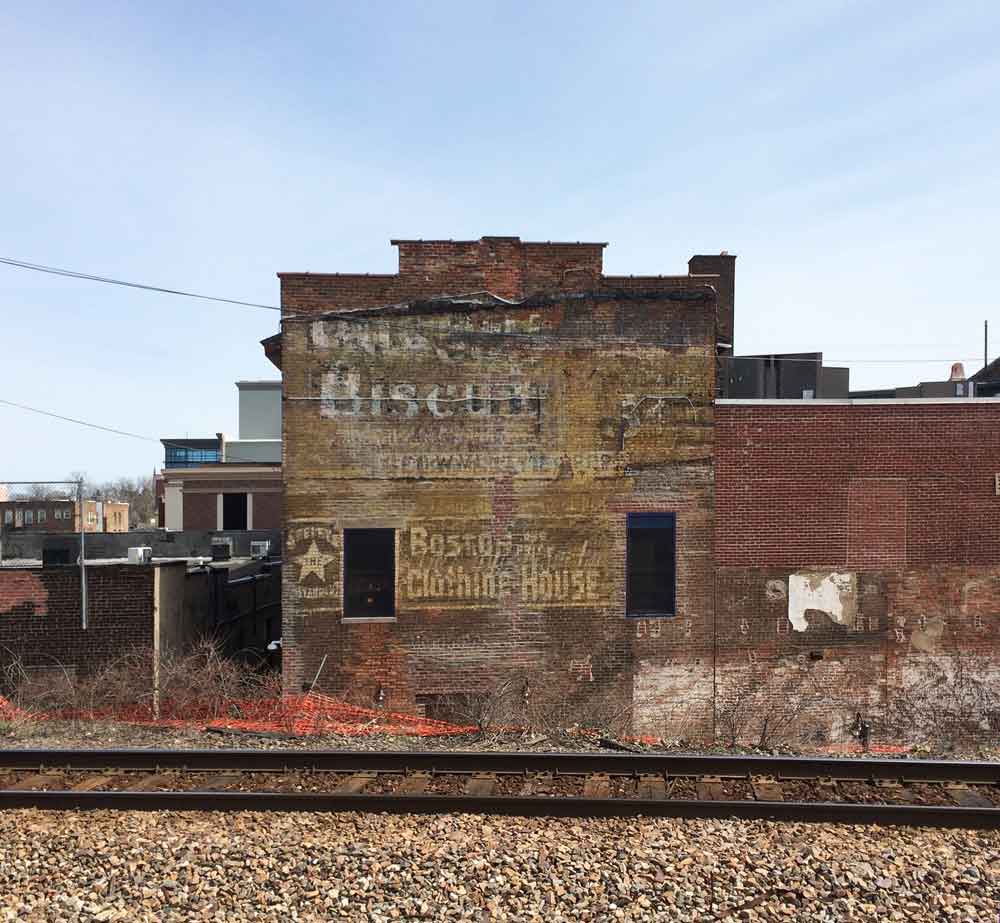

Fig. 1: Uneeda Biscuit ghost fragment on the former Nicholaus Block on the corner of State Street and Erie Boulevard, Schenectady, New York. Demolished in 2017.

In 2016, an early Uneeda brick face sign was discovered on the west wall of the Nicholaus Block, on the corner of State Street and Erie Boulevard in Schenectady, New York. As is often the case, the sign was exposed when the building next door was demolished. A fragment only, the ghost was well preserved, retaining the typically washed away fugitive reds, greens and blacks that were central to the product’s identity. It was novel enough to make the local news.2 I didn’t know what “Une Bis” was, but it took just a few minutes of Googling to figure out that this was something special.

It wasn’t the first old sign I’d ever noticed. I’d been documenting them for a while. But this Uneeda fragment’s sudden appearance made an impression, and since, ghosts have been popping into my consciousness with ever more frightening frequency.

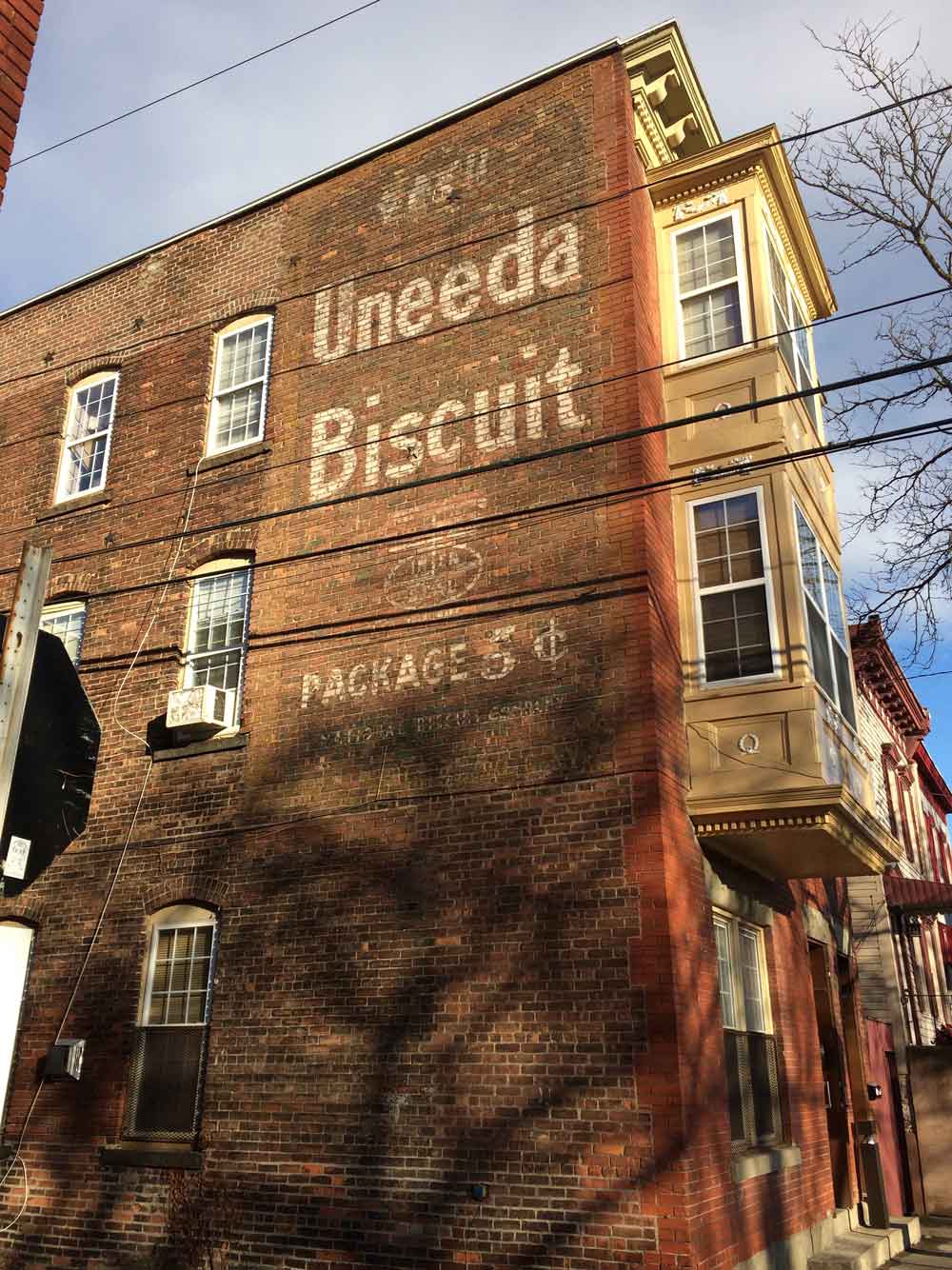

Fig. 2: Uneeda Biscuit double ghost on the west wall of 325 State Street, Schenectady.

As it turned out, though unnoticed by me, a second Uneeda survivor stood out in the open no more than 100 yards from the first. It is painted across the upper stories of a Mexican restaurant at the base of Schenectady’s Amtrak platform. Like many of its kin, most of its original colors are gone. But in weathering, it has exposed layers of history bound in its mustard matrix. According to the blog Lost Landmarks of Upstate New York,3 the collage of signs on this wall points to a creation date no later than 1901. That would make the Uneeda ghost, if original, one of the oldest anywhere.

The First Mass Media Campaign

The National Biscuit Company was founded on February 3, 1898 through the merger of the rivalrous American Biscuit & Manufacturing Company and the New York Biscuit Company (along with the United States Baking Company and a few smaller concerns). The name “Uneeda,” the invention of NBC’s advertising agency, N. W. Ayer & Son, was registered on December 27, 1898. By that January, less than a year after the company’s founding, Ayer kicked off a teaser campaign with a Chicago newspaper display ad that read simply, “Do you know Uneeda Biscuit?” Demand was immediate,4 and an unheard of 10-year $7,000,000 advertising budget was requested.5

Outdoor advertising, the first mass media, had exploded only in the decade before, made possible by advances in lithography and inspired by the success of “the circus is coming to town” posters pasted on barns across the country by advance men for P. T. Barnum and others.6

But Ayer’s Uneeda campaign was of an industrial scale not seen before. According to Laura E. Baker in “Public Sites Verses Public Sights,” at one point, NBC estimated that 30 million people saw a Uneeda ad every day.7 Based on the density and frequency of the brick face postings, it is likely a trolley-riding commuter would see two, three, four or more on their way to and from work – bright commercial breaks in a soot-streaked urban drama.

Fig. 3: Uneeda Biscuit ghost at Ferry Street and Williams Street Alley, Troy, New York.

Following a trail established earlier by a local photographer,8 I was able track down six additional Uneeda ghosts within 20 miles of Schenectady, two in Albany, one in Cohoes and three in Troy.

At Ferry Street and Williams Street Alley in Troy stands one of the most legibly preserved. Though the dark green field and red octagon around the IN-ER-SEAL logo (which would evolve into the Nabisco logo) are faded, the white lettering remains bold and clear.

Prominent is the price, 5¢.

It was by no means a given that Uneeda Biscuits would be sold in a standard 21-cracker per box for five cents configuration. Prior, crackers were simply shoveled out of a barrel into a bag and sold by weight. And five cents per package left almost no margin for profit even in 1899. Several NBC investors pushed against the strategy. But Adolphus Green, the visionary manager of NBC, was certain the future of grocery retailing was high volume, low price and product standardization.9 His instincts were correct. The ability to convert a nickel into a box or a bottle of something good proved a magic formula. A big “5¢” appeared not only on Uneeda Biscuit signs, but also on Coca-Cola, Pepsi Cola and other soft drink promotions, Owl and Cremo Cigar promotions, and many other prominent promotions of the era (hence my speculation about well-worn Buffalo nickels).

Fig. 4: Uneeda Biscuit ghost at 65 Remson Street, Cohoes, New York.

Why Do They Persist?

As previously stated, thousands of Uneeda signs were painted, and the fact that many are still with us is in part simply a function of this promiscuity. But there are other reasons why they survive.

Just north of Troy, on Remson Street in Cohoes, stands an example that helps tell the story. Ayer’s field agents had money to spend, and in the absence of any legal obstacles, were able to make leasing agreements with private property owners for what was often virgin wall space. Good locations attracted generations of advertisers. But as the Remson Street example shows, even after being painted over multiple times, the lead white used for the primary lettering, which chemically bonded to bricks below, has allowed the Uneeda originals to hold fast, and with time, weather back into view.

Living with Ghosts … and Letting Them Go

Nabisco discontinued the Uneeda Biscuit in 2009. The product’s rise and fall tracked exactly with the rise and fall of mass media. Not at all a coincidence. In the era of Yelp and Twitter, paid mass media has lost much of its power to move the sales needle. And standardized package goods have lost much of their communal allure.

But with these changes, a certain nostalgia has kicked in.

Fig. 5: Restored Uneeda Biscuit brick face, N. Salina Street, Syracuse, New York.

Ghosts located in gentrifying downtown districts are now routinely repainted by developers and community supporters to signal the “authentic” urbanity of their neighborhoods, and promote the new microbreweries, farm-to-table bistros and other re-localized artisanal businesses. Ironic, as mass-produced products like Uneeda were largely responsible for driving urban artisans out of business.

Despite the irony, these efforts should be celebrated. While the decision to repaint a ghost or let it weather is a difficult one, and can only be answered on a case by case basis, repainting may very well protect the original layer, which may allow it to reemerge a century from now. But any notice, any awareness is a good thing, because we are in the middle of an extinction event. Over just the last 10 years, Schenectady has lost three of its four surviving Uneeda brick faces, including the Nicholaus Block fragment discussed above, all to nothing but empty lots.10

Endnotes

[2] Viccaro, Haley. “Demolition Reveals Ghost Sign in Schenectady.” The Daily Gazette, February 24, 2018, https://dailygazette.com/article/2016/03/16/demolition-reveals-ghost-sign-schenectady.

[3] (Photos by Howard Ohlhous). “Time of the Signs.” Lost Landmarks of Upstate New York (blog), http://www.lostlandmarks.org/schentrain.html.

[4] According to Carl Weinberg in an OAH review of a teaching strategy authored by Pamela Laird and Catherine Canavan, Uneeda Biscuits were a runaway hit, selling 10 million biscuits a month within one year of their introduction in 1899.

[5] For a detailed account of the development and launch of the Uneeda Biscuit campaign, see: Cahn, William. 1969. Out of the Cracker Barrel. New York: Simon and Schuster.

[6] The connection between circus posters and brick face promotions was a favorite theory of Deloney Sledge, a former Coca-Cola VP of advertising. Moye, Jay. “’Ghost Signs Reborn’: Restored Coca-Cola Murals Refresh Southern Downtowns” (blog).

[7] Baker, Laura E. 2007. “Public Sites Verses Public Sights: The Progressive Response to Outdoor Advertising and the Commercialization of Public Space,” p. 1191.

[8] Ghosts signs of New York’s Capital Region have been extensively documented by photographer and writer Chuck Miller. See: Miller, Chuck, “Photo Essay: The Ghost Signs of the Capital District,” Times Union, January 25, 2010. Accessed on March 10, 2018 at https://blog.timesunion.com/chuckmiller/photo-essay-the-ghost-signs-of-the-capital-district/903/.

[9] Cahn, p. 86.

[10] As of this writing, you can use Google Maps to visit the corner of Broadway and Edison Avenue in Schenectady and see an empty lot. But if you click down Edison, then turn right, you can see both a now-demolished Uneeda Biscuit and Coca-Cola ghost.

References

Chan, William. 1969. Out of the Cracker Barrel: The Nabisco Story from Animal Crackers to Zuzus. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Laird, Pamela Walker. “Bringing in Business History Front and Center.” OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 24, No. 1, Business History (Jan., 2010), pp. 7-8.

Moye, Jay. “’Ghost Signs Reborn’: Restored Coca-Cola Murals Refresh Southern Downtowns.” Coca-Cola Journey blog, May 25, 2016. Accessed on March 2, 2018 at http://www.coca-colacompany.com/stories/ghost-signs-reborn-restored-coca-cola-murals-refresh-southern-downtowns.

Sivulka. 2012 (1998). Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes (Second Edition). Boston: Wadsworth.

Weinberg, Carl. “Uneeda Read This.” The OAH Magazine of History, January 2010, http://archive.oah.org/magazine-of-history/issues/241/weinberg.html.

Wilson, William E. “The Billboard: Bane of the City Beautiful.” Journal of Urban History, Vol. 13 No. 4 (August 1987), pp. 394-425.

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2018, Vol. 36, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA