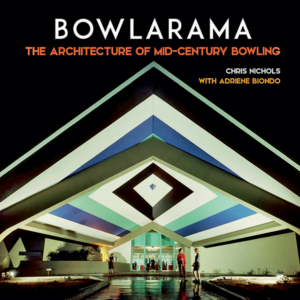

Bowlarama: The Architecture of Mid-Century Bowling

By Chris Nichols with Adriene Biondo

Angel City Press, 2024

Hardcover, 176 pages, $40

Reviewed by Ronald Ladouceur

[See: SCA Zoom Recording by Bowlarama’s co-author, Chris Nichols]

Bowling, believe it or not, remains the most popular participatory sports in the United States (or second most if you include corn hole), and its popularity is currently on the rise. Entrepreneur Tom Shannon, through his company Bowlero, has “re-hippified” the sport, riding the Millennial generation’s rediscovery of all things exotica. Bowlero currently operates more than 325 bowling centers across the U.S. and Puerto Rico and has plans to expand to 700 lanes by 2027. Still, impressive as this is, the total number of bowling alleys open today, just under 3,000, is only a fraction of the number that were in operation at the height of the sport’s popularity, the early to mid-1960s, when there were more than 12,000 centers across North America.

Bowling, believe it or not, remains the most popular participatory sports in the United States (or second most if you include corn hole), and its popularity is currently on the rise. Entrepreneur Tom Shannon, through his company Bowlero, has “re-hippified” the sport, riding the Millennial generation’s rediscovery of all things exotica. Bowlero currently operates more than 325 bowling centers across the U.S. and Puerto Rico and has plans to expand to 700 lanes by 2027. Still, impressive as this is, the total number of bowling alleys open today, just under 3,000, is only a fraction of the number that were in operation at the height of the sport’s popularity, the early to mid-1960s, when there were more than 12,000 centers across North America.

Bowlarama: The Architecture of Mid-Century Bowling (2024) by Chris Nichols with Adriene Biondo is a chatty and charming companion to Thomas Hine’s Populuxe (1986) and Alan Hess’s Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture (1986). Bowlarama, a handsome, fact-filled book chronicles the entire history of bowling, but focuses the half half-decade between 1957 and 1962, when separate streams of technology, suburbanization, and entertainment culture combined to fuel the development of fantastic and monumental architectural confections throughout the west and across the country. During those five years, eyepopping “California modern” bowling centers spang up along the miracle miles spiking out from city centers, and in the hands of the most aggressive developers, ballooned into near-Vegas-level entertainment venues.

Nichols and Biondo’s book grew out of a 2014 exhibition at the A+D Architecture Museum documenting a campaign to preserve Covina Bowl. Designed by the firm of Powers, Daly and DeRosa, when it opened in 1956, Covina Bowl ignited a bowling center arms race.

Postcard of Covina Bowl, Covina, CA. Charles Phoenix.

Nichols is a historian, popular lecturer, and writer for Los Angeles magazine. Biondo is a very active writer and preservationist who lists among her many accomplishments initiating nominations for key mid-century landmarks including the Capital Records building in L.A. Their book, though written for a casual reader, references many scholarly works familiar to roadside aficionados, including Hess’s Googie and Hine’s Populuxe mentioned above, along with Chester Liebs’s Main Street to Miracle Mile (1985), and of course Robert Putnam’s famous social history, Bowling Alone (2000). The authors supplement their secondary sources with a casual review of primary documents, including industry publications and promotional videos, and most significantly, 30 first-person interviews conducted over a 10-year period with the architects, owners, entertainers, and players who were active during bowling’s mid-century heyday. An invaluable archive, as many have since passed away.

The colorful characters highlighted in Bowlarama include architect Richard Barancik (1924-2023), famous as the last surviving member of the “Monuments Men,” the Army group assigned to recover and repatriate thousands of artworks looted by the Nazi’s during World War II. Barancik disclaimed his contribution, noting that he had minimal artistic knowledge and during the time he was assigned to the operation only ever saw crates, not the artworks themselves. But his involvement did lead to enrollment at the University of Cambridge, and from there a study abroad at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. There he met Le Corbusier, the famed modernist, only to be disappointed by how filthy the minimalist’s office was. Back in the States, Barancik was equally unimpressed by his audience with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin, put off by Wright’s imperiousness. Described by Nichols and Biondo as “brilliant and bristly,” with (quoting the architect) “‘a low tolerance for bullshit,’” Barancik kicked off the fashion for archway entrances with his 1959 design for Orchard Twin Bowl in Skokie, Illinois, inspired certainly by Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch in St. Louis (though the latter was still 3 years from construction start).

Also highlighted in Bowlerama are performers like Rusty Warren, a groundbreaking female comedian famous for working “blue,” and described by one 60’s journalist as the “Mother of the Sexual Revolution” for her upfront treatment of sexual themes and female sexual pleasure. She and other up-and-comers honed their acts in the bowling “showroom” circuit. That there was a bowling showroom circuit, complete with Vegas-style lounges, is one of the many delightful surprises the casual reader will discover in Bowlarama. hough, how Mel Torme, Dan Rowen and Dick Martin, or the Supremes (at the time still the “no-hit Supremes”) competed with 40 or so active lanes remains a bit of a mystery.

Bowlerama’s central and strongest chapters explore the exterior architecture and interior decoration of mid-century bowling centers. The authors present the form not as kitsch, but in the hands of architects like Armet & Davis and Powers, Daly, & DeRosa, and artists like Arene Lagorio, avant-garde artistic expressions which flowered spectacularly (if only briefly) in the arid suburbs of the southwest. Nichols and Biondo convincingly connect the “big names” of modern architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Le Corbusier, through their “Californian-ized” students, Rudolf Schindler and Richard Neurtra, to the less famous masters of the form. The authors do note humorously how many of the “big name” architects failed when they tried their hand at designing bowling centers, when for example they insisted on glass walls that allowed the sun to reflect distractingly off the alleys or when they stripped their centers of ornament, reducing them to a functionalist ideal, not the fantasy escapes the mid-century public desired.

Of course, central to bowling’s growth and cultural impact were the parallel introductions of the automated pinsetter and a revolution in design made possible by plastics.

Vintage Brunswick Scoring Table.

Prior to the automatic pinsetter, the employment and deployment of pinboys, the often underage or itinerant “muscle” that manually reset bowling pins after each throw, proved a major impediment to industry growth and popularity. Pinboys were a difficult bunch, rowdy, heckling, and unreliable. Though systems to automate the reset process took decades to develop, their introduction in the mid-1950s revolutionized the industry by sweeping out the pinboy and welcoming in the family. Simultaneously, industrial designers like Raymond Loewy and the very influential Donald Deskey, who was employed by Brunswick, the country’s major equipment vendor, introduced Americans to a futuristic style in the form of sleek and colorful ball returns, scoring stations, plastic furniture and the omnipresent seat back cup holder.

Though not the focus of their book, Nichols and Biondo also touch on bowling’s social history, which, unsurprisingly, tracks with the history of segregation in the United States. Prior to World War II, almost all players were white men. After the war, women were welcome (having filled the lanes during the war). But it wasn’t until 1950, after Asian and Black players sued, that the ABA dropped its constitutional provision that members had to be white. Even after, bowling remained largely segregated into the 1970s.

So, what caused the bowling bubble to pop in the early 1960s? Nichols and Biondo cite several possible causes: a growing ecological awareness linked to a general disparagement of large roadside promotions, a retreat from forward-thinking optimism, and specifically the “Kennedy Slide” or “Flash Crash” of 1962, an event the authors believe was most proximately responsible for the sudden end to the bowling center boom. Developers had overbuilt on what turned out to be a shaky (and shady) financial foundation. But perhaps it was more than that. Though bowling remained a popular activity into the 1960s, and remains reasonably popular today, the era of space-age optimism signaled by the exuberant architecture of arches, pyramids, and flying porte-cochere, intimately linked as it was to a lounge culture, became instantly uncool the second the Beatles landed at Kennedy.

Ronald Ladouceur is the principal and founder of POSTMKTG, an Upstate New York branding and design agency. He is also an adjunct lecturer at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the University at Albany and serves on the SCA board.

This book review originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2024, Vol. 42, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Book Reviews