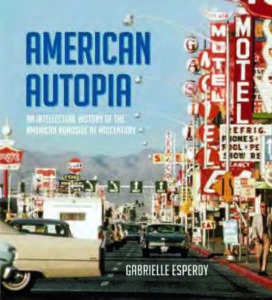

American Autopia: An Intellectual History of the American Roadside at Midcentury

By Gabrielle Esperdy

Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2019.

384 pages, Cloth, $49.50

Reviewed by Ralph S. Wilcox

The introduction of the automobile into American life in the early 20th century brought a myriad of changes to the landscape. American auto travelers required new types of facilities that weren’t needed with wagon and railroad travel. Gas stations, service garages, motels, and tourist courts sprouted up along the highways of the U.S. like plantings in flower beds along a sidewalk. The book American Autopia: An Intellectual History of the American Roadside at Midcentury examines how the development of the automobile changed the American landscape, and how the changes appeared to contemporary sources.

The introduction of the automobile into American life in the early 20th century brought a myriad of changes to the landscape. American auto travelers required new types of facilities that weren’t needed with wagon and railroad travel. Gas stations, service garages, motels, and tourist courts sprouted up along the highways of the U.S. like plantings in flower beds along a sidewalk. The book American Autopia: An Intellectual History of the American Roadside at Midcentury examines how the development of the automobile changed the American landscape, and how the changes appeared to contemporary sources.

One of the strengths of Gabrielle Esperdy’s book is the wide variety of sources and topics it covers. Arranged in chronological order, the book starts at the beginning of the 20th century and the new building types that developed as a result of the automobile’s increasing popularity. Cars required gas stations and parking garages, among other things, and as people embraced the automobile for travel, the tourist court and motel developed to accommodate travelers. By midcentury, the development of suburbs was a response to what the car allowed in American life. People no longer needed to work and live in cities, nor did they have to shop in downtowns, as evidenced by the development of the shopping mall.

Even during the Depression, the importance of the automobile was celebrated, most notably with the development of the American Guide series completed by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration. Esperdy discusses the series and what it brought to the idea of automobile travel. The guides included tour descriptions with mileages, information on towns and sites along the routes, and encouraged motorists to use the itineraries as the basis for their own trips. Interestingly, though, Esperdy never mentions The Negro Motorist Green Book, which also developed during the 1930s and was a vital travel aid.

The end of the period covered by Esperdy’s book is the oil crisis of the early 1970s, which changed the design of the automobile. Gone were the land yachts of the previous decades, and the crisis also changed (at least temporarily) the way that the car was used. Esperdy also discusses the professional study and documentation of the roadside, as well as the founding of the Society for Commercial Archeology, both of which occurred during this period.

The thoroughness of Esperdy’s book is hinted at on the dustjacket, which notes that it has a narrative that “extends from U.S. Routes 1 and 66 through the Las Vegas Strip and California freeways, with stops at gas stations, diners, main drags, shopping centers, and parking lots along the way.” The wide variety of topics that Esperdy touches on is one of the book’s strengths—it’s an excellent reference on highway history for the early-and mid-20th century. However, reading the book straight through is a challenge; there’s a lot to absorb, and it’s better digested in segments. The text is supplemented by a wide variety of illustrations, although it could have used even more images.

As one who writes National Register of Historic Places nominations, sometimes for resources along the American roadside, I can see referencing Esperdy’s book in my work. I would recommend the book for those in academia or interested in the analysis of the roadside’s development. Esperdy’s book is a valuable addition to the scholarship of the American Roadside, its landscape, and its interpretation.

Ralph S. Wilcox is a former SCA Secretary and was one of the key planners of the 2010 SCA Conference, Odyssey in the Ozarks.

This book review originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2020, Vol. 38, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Book Reviews