One of the most popular themes along America’s pre-interstate roadside has, since the 1970s, quietly evanesced like a genie disappearing into its bottle.

Yet, judging by the signs and dated promotional ephemera, the Near East (the Arabic countries of the Middle East and North Africa) may have rivaled Polynesia as America’s favorite escape for people seeking a foreign destination during their domestic travels.

Mecca Café, Ft. Stockton, Texas

For most of the 20th century, the Near East captivated Americans, its influence extending coast to coast. Countless owners of motels, restaurants and nightclubs bet their economic futures that naming their business after elements of this region would bring success. Namesakes included place names (Morocco Lounge in Portland, Maine), monuments (Luxor Motel in Danville, Illinois), historical figures (Cleopatra Lounge in Omaha, Nebraska), literary figures (Ali Baba Club in Oakland, California) and natural features (Sands Motel in Vaughn, New Mexico).

Caravan at the Las Palmas (formerly Egyptian) Motel, Phoenix, Arizona

The Near East has an amazing allure; it’s where many ancient civilizations flourished and world religions were born. The region’s famous monuments and harsh but romantic landscape of palm tree-fringed oases surrounded by endless sand dunes stirred our imaginations. Despite this impressive resume, three phenomena—an animal, a carnival sideshow and a war—were important catalysts that, for a period, transformed American’s vision of the region into a carefree place to relax and party.

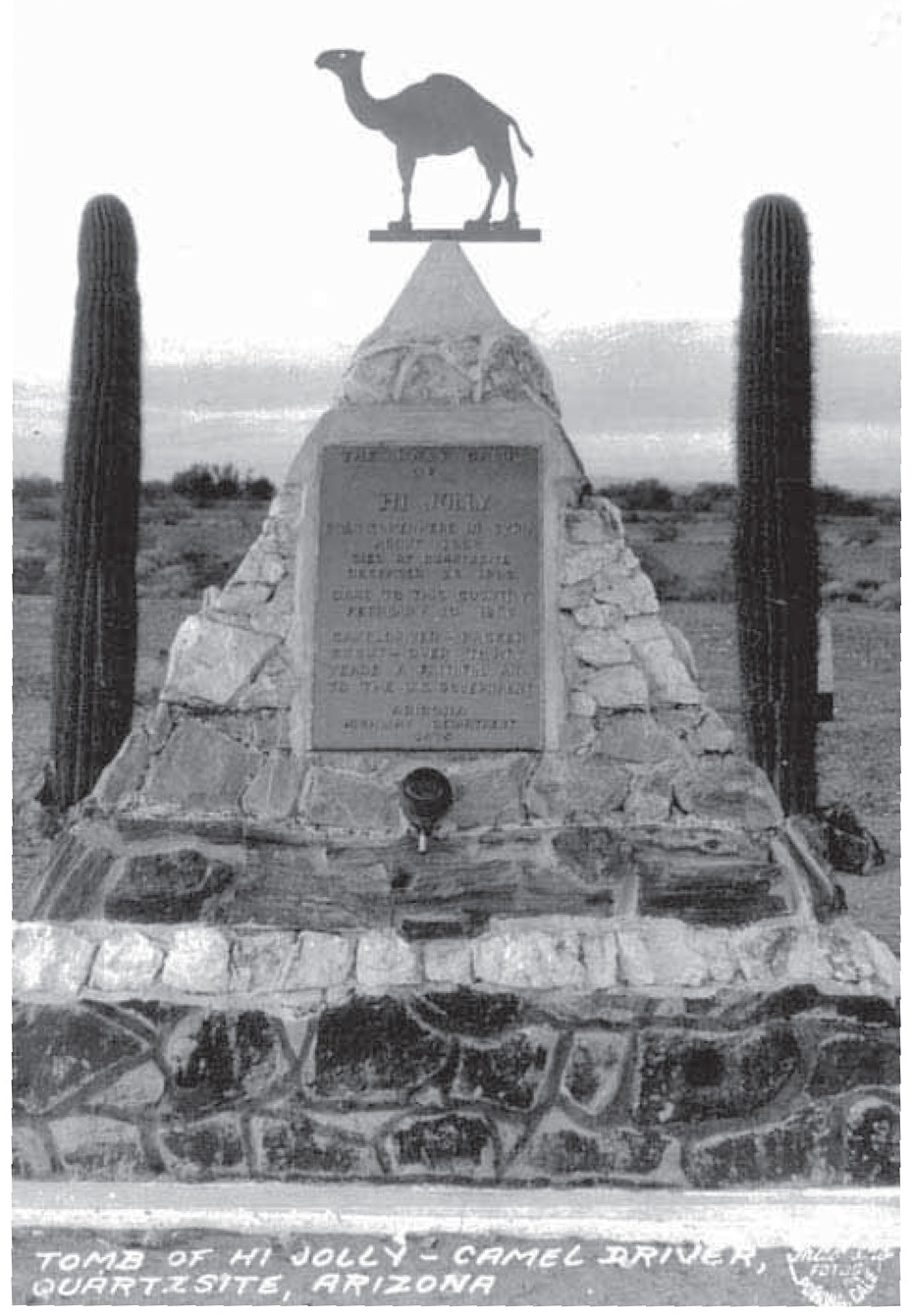

Hi Jolly Memorial, Quartzsite, Arizona

A beast of burden indelibly associated with the Near East served as an early ambassador. In 1855, the U.S.S. Supply sailed to the Mediterranean in search of camels—and men who knew how to handle the often cantankerous animals. The U.S. government hoped they would prove valuable in transporting goods in the arid Southwest. Thirty-three camels were brought back to America along with some handlers, of which Hi Jolly (or Hadji Ali) proved the most skilled. After landing in Texas, the camels were led to Albuquerque where an expedition under the command of Lt. Beale headed west to California following a path similar to what would become Route 66. The camels handled by Hi Jolly performed superbly although were disliked because of their temperament by the accompanying soldiers and horses.

Club Algerian, Denver, Colorado

Despite this impressive dromedary drive, the U.S. Camel Corps was soon disbanded because of changing political leadership. Hi Jolly retained some animals to supply mines in southwestern Arizona. Few other people, however, knew how to control the camels and many became feral desert creatures. The last camel was reportedly captured in Arizona in 1946 though some were seen in Mexico as late as 1956. Hi Jolly, who died in 1902, spent his later years in the Arizona town of Quartzsite. There, the Arizona Highway Department erected a stone pyramid to honor him. The town annually celebrates Hi Jolly Daze, one of the few grassroots events in America celebrating a Muslim immigrant from the Near East.

Aladdin’s Lamp, Fremont Street Experience, Las Vegas, Nevada

Another Near East influence can be traced to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago. The fair’s midway was the most popular draw, lined with international concessions that included markets, cafes, and theaters as well as tethered balloon rides and the world’s first Ferris wheel. The most popular stop along the midway was “A Street in Cairo” which showed how people of the Egyptian city lived, transacted business, and amused themselves. The attraction featured camel rides, a bazaar, and on stage, dark-eyed Egyptian girls in gauzy garments with golden ornaments in their head dresses and tiny cymbals upon their fingers performing the infamous danse du ventre—or belly dance. Accompanied by Egyptian musicians, the dancers played to packed male audiences. When a puritanical vice-hunter made headlines condemning the show, its notoriety only grew.

Mecca Restaurant & Bar, Baltimore

The fanfare created by the Egyptian dancers was so great that many urban legends grew from their act. These yarns included Thomas Edison filming them and Mark Twain suffering a heart attack after witnessing a performance. The most renowned tale, however, was that of the dancer, “Little Egypt,” who is alleged to have made her debut at the 1893 Exposition. To capitalize on the success of “A Street in Cairo” after the Exposition closed, a number of dancers, all calling themselves “Little Egypt” toured the country, performing in burlesque halls to scandalous acclaim.

Egyptian Room, Sioux City, Iowa

The ambiance of the Near East was also brought stateside after World War II by troops returning from North Africa where the U.S. first entered the land war against Germany. Although the Polynesian craze that swept America in the post-war years is well documented, little has been written about the many Near East-themed nightspots that opened after the troops came home.

El Morocco, Santa Clara, California

Although the food served by these clubs was standard American fare, the establishments captured the spirit of the region in other ways. Minarets were often part of the building’s architecture and, inside, the feasts took place under a backdrop of desert caravans, palm trees, and harems of belly dancers, all under the watchful eyes of a Sphinx. Obviously, this romanticized version of an exotic culture worked; after a hard day’s work, what man didn’t enjoy a magical night imagining himself a sultan and what lady, Cleopatra?

Luxor Motel & Dining Room, Danville, Illinois

While the Polynesian culture continues to inspire devoted adulation, there appears to be no particular outcry at the loss of the faux-Near East businesses. Perhaps because our relationship with the culture is more problematic, influenced by the region’s political issues and 9/11. Will the Near East’s entrenched problems improve? Will the surviving faux-Near East establishments ever be as cherished as those from the South Seas? I don’t know, but on my next Vegas trip, I’ll rub the Aladdin’s Lamp that is preserved at the Las Vegas Neon Museum and wish for good luck on both accounts.

All images courtesy of Douglas Towne

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2009, Vol. 27, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA