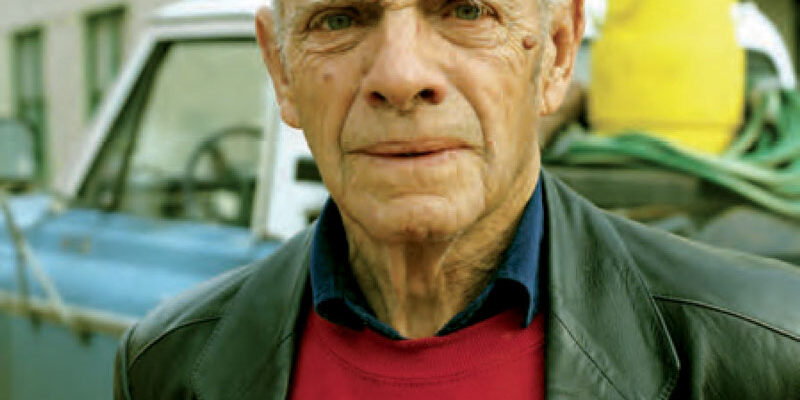

Traces of J.B. Jackson: The Man Who Taught Us to See Everyday America

By Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz

University of Virginia Press, 2020

Hardcover, 328 pages, 51 color and b&w illus., $39.50

Reviewed by Philip Langdon

If commercial archeology had a patron saint, it would doubtless be John Brinckerhoff Jackson. A writer of originality and eloquence, Jackson focused on commonplace buildings and settings for much of his life, including gas stations, roads, signs, and other elements of an automobile-propelled nation.

If commercial archeology had a patron saint, it would doubtless be John Brinckerhoff Jackson. A writer of originality and eloquence, Jackson focused on commonplace buildings and settings for much of his life, including gas stations, roads, signs, and other elements of an automobile-propelled nation.

From his home New Mexico in 1951, Jackson, in his early 40s, launched the journal Landscape, at first writing every word of it himself. So perceptive were his essays that soon the publication attracted a stable of distinguished contributors. Blessed with a resonant baritone and a wry self-confidence in front of an audience, by the 1960s, he was recruited into guest-lecturing at Berkeley and Harvard— something he continued to do for nearly 20 years despite his misgivings about academia. With his independent-mindedness, he inspired designers, geographers, historians, and others to look with inquisitive eyes at parts of the man-made environment that earlier commentators had largely detested or ignored.

Not long before his death at age 86 in 1996, Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz found Jackson tossing his papers—which he’d come to see as a burden—onto a bonfire outside the house he’d built in 1965 in La Cienega, a mostly Hispanic town near Santa Fe. Horowitz, a cultural historian who had befriended Jackson in the early 1970s and remained close to him for more than two decades, rescued all she could. Plenty survived, including letters and travel journals, not to mention his several books of published essays. She digested all of it for insights into a complex man and his work.

The result is Traces of J.B. Jackson, a piercingly intelligent chronology that follows Jackson year by year and sometimes week by week as he proceeds from a privileged boyhood in the U.S. and Europe, to study at prep schools and Harvard (class of 1932), to dalliances with architecture, commercial art, and newspaper work, to a stint as a novelist, periods spent ranching in New Mexico, military intelligence assignments in World War II, and travel, travel, and more travel.

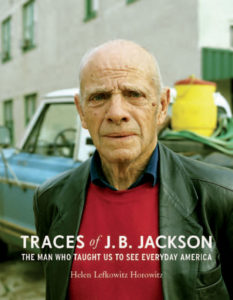

Confi Guide was an annual compendium of Harvard students’ critiques of courses that published this cartoon of Jackson in 1974. Jackson taught the class, “Studies of the Man-made American Environment since the Civil War,” which undergraduates nicknamed “Gas Stations.” The publication nicknamed Jackson as “the Motorcycle Maniac” for his cross-country solo motorcycle trips.

“I’m pro-automobiles,” Jackson had impressed upon Horowitz. (He was also an avid motorcyclist.) In the pre-Interstate 1950s, he would think nothing of driving from the East Coast to New Mexico—studying small towns along the way. He sketched scenes, observed how people used main streets and outlying roads, made maps of how the communities grew, and spent nights at tourist courts. The $5.50-a-night Shangri-La court in St. Joseph, Kansas—pronounced “very luxurious” by the restless, roving editor—was one stop on a 1954 excursion that caused him to think about publishing an issue on the “birth, growth & influence of a highway,” including “Interviews with filling stations, chambers of commerce, highway patrol, highway Department, merchants, farmers, motels.”

Horowitz says Jackson “enjoyed the messiness and hurly-burly of American life.” In his 1985 essay “The Vernacular City,” Jackson argued that in newer, fast-growing communities like Lubbock, Texas, “the street, the road, the highway has taken the place of architecture as the basic visual element, the infrastructure of the city.” He took pleasure in the exuberance of the Strip, accepting “all those streamlined facades … those flamboyant entrances and deliberately bizarre decorative effects, those cheerfully self-assertive masses of color and light and movement.”

During a 1956 New Mexico jaunt, he noted that beyond the town centers, nearly every commercial building was “the same one-story cube,” the only variation being “some slight indication of its function—a gas pump, a front yard, a shop window—and the signs on most of them. Within the towns themselves, the only way a building can distinguish itself is by having signs—as many signs as possible, large, vertical, and when possible lighted up.”

Signs, he maintained, are essential to popular commercial architecture. In such architecture, he said, “functional & decorative features are distinctly separate, each is allowed to play its part.” What stands out in this passage is how close in spirit his 1956 observations were to ideas that Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown would famously propose years later.

Traces is a warts-and-all portrait. Jackson was “born in 1909 into a family with elite aspirations,” says Horowitz, and he “inherited many of the narrow-minded views of the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant establishment of his day.” Living off inherited wealth, in his youth, he looked down on common folk. In travel journals as late as the 1950s, Horowitz, who is Jewish, was dismayed to find Jackson making disparaging remarks about Jews and African-Americans.

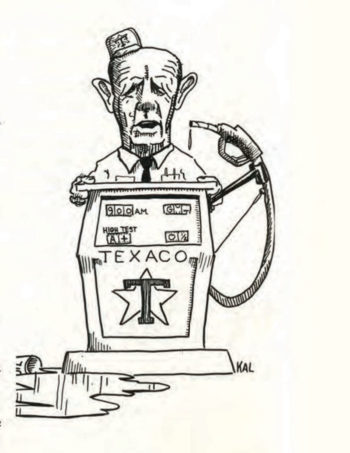

Jackson’s “Telephone Poles” was a sketch he made in his jeep, according to Horowitz. She says, “Jackson could see and put front and center what others often choose to avoid, the poles and wires along the road, not just the land and trees.”

Yet as time went on, and as editing Landscape expanded his contact with others, his prejudices receded; he developed an appreciation for ordinary people as well as ordinary buildings. In his last couple of decades, he regularly reached out for working-class companionship. His blue-collar Hispanic neighbors were welcomed into his La Cienega home practically every afternoon. In the 1980s, he began working at a service station and did outdoor physical labor.

From a very early age, Horowitz says, “Jackson enjoyed being a contrarian.” That posture helps to account for some of his views. He continued venerating the automotive way of life, for instance, even after America’s roads had given up most of their quirky expressiveness. He didn’t adjust to the times and see that the country might be better off with a less car-dominated transportation network.

Nonetheless, the writing he left us remains sharp, engaging, and often subtly humorous; it challenges readers to see things from a radically different perspective. Jackson was an extraordinary devil’s advocate, and Horowitz’s book skillfully plumbs his character, exploits, and genius.

For people not already familiar with Jackson, Traces is not the first book they should read. They should pick up one of Jackson’s several collections of essays—Landscape in Sight: Looking at America from 1997 might be a place to start—and read a bunch of them. After doing that, they’ll be in a position to appreciate Horowitz’s book much more fully. Traces of J.B. Jackson is worth the effort; it’s a clear-eyed portrait of the man who did indeed teach us how to see everyday America.

Philip Langdon’s books include Orange Roofs, Golden Arches: The Architecture of American Chain Restaurants (1986), and Within Walking Distance: Creating Livable Communities for All (2017).

EXTRA INSIGHTS

Traces of J.B. Jackson Book Review

By Daniel Scully

J.B. “Brinck” Jackson had a profound influence on my architectural career.

His writings were assigned reading at the start of the Venturi/Scott-Brown Learning From Las Vegas Studio, at Yale in September 1968. Among the readings: “Other Directed Houses,” Landscape (Winter 1957); “The Abstract World of the Hot-Rodder,” Landscape (Autumn 1957); and “The Four Corners Country,” Landscape (Autumn 1960).

For me, the definitive clarity, paraphrasing mostly from the first reference and “The Social Landscape” articles, came with Jackson’s equation of the European Piazza as the social space, and the realization that in the U.S., cruising Main Street is the analogous social space; one a fixed place, the other defined by being in motion. As one who had majored in American Studies and Art in college, with great interest in the automobile in our culture, I felt he, along with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown, made a crystalline clear “guide” in the thematic direction of my architectural design for more than 50 years.

My role in the Learning From Las Vegas Studio, along with Peter Schmitt, was called “Communication,” essentially buildings as communication systems. Personally, Venturi and Scott-Brown validated, legitimized, and put meat on the bones of utilizing the automobile as a source of architectural design inspiration and imagery, an influence as worthy of architectural study as any other in history. This concept was central in freeing me to trust myself, to follow my own road. I spent 1972 teaching, with a field course documenting the diners along New Jersey Route 17.

When a disparate group of roadside obsessives, historians, planners, archaeologists, and others devoted to comfy food and architecture started the Society for Commercial Archeology in Burlington Vermont in 1977, I think the majority wanted to soak up stainless diner history. But there was a growing interest in expanding the roadside architectural phenomena awareness. Geographer Arthur Krim would push to save the huge pulsating CITCO sign in Kenmore Square in Boston. In 1985, Chester Liebs published Main Street to Miracle Mile: American Roadside Architecture, which has two brief Jackson quotes and one Venturi/Scott-Brown reference.

As for the others, I am not sure if Jackson or Venturi/ Scott-Brown had been conscious influences, but the diner as a topic of study was intense and growing. Undoubtedly during that period, the work of Jackson helped define the understanding of the “landscape” of the highway.

Dan Scully is a former SCA President in 1979 whose firm, Scully/ Architects, practices predominantly around Keene, New Hampshire. Scully/Architects operates much like a general practice doctor, doing all scales of buildings in support of building the community. The lessons from Jackson and Venturi/Scott-Brown generally are not overt, but reveal themselves subtlety.

This book review originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2020, Vol. 38, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Book Reviews