Construction frame of the world’s largest rotating sign, January 1958. All images from Arizona Contractor & Community magazine.

The internet is rife with dubious claims of eagles swooping down to carry away small children. Overlooked, however, is the day a raptor saved a Phoenix man’s life with its wing.

This heroic bird was no ordinary eagle, but rather part of Valley National Bank’s 35-foot-tall sign, installed high above downtown Phoenix in 1958. The octagonal sign used the bank’s blue and yellow eagle symbol, whose 49-foot wingspan turned out to be a lifesaving feature for one maintenance worker.

The large sign was an apt symbol of Valley National Bank’s success after World War II. The bank grew with Arizona and had 51 branches across the state by the late 1950s. Each office displayed the company’s bird of prey, but none quite so dramatically as the central bank office in the Art Deco Professional Building in downtown Phoenix.

See also: Behind the Story: The World’s Largest Revolving Sign

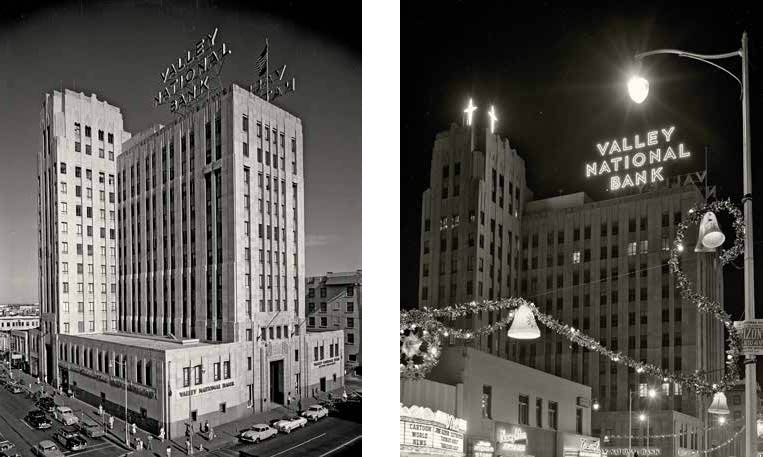

Left: Professional Building as it appeared in 1953. Right: Professional Building decorated for the holidays, 1954.

Completed in 1931, the 12-story skyscraper was to be called the “Valley Bank Building.” Because of the many bank failures during the Great Depression, the name was changed to the Professional Building to focus attention on its medical tenants.

In recognition of their financial prosperity, the bank added a glass-enclosed, executive penthouse to a wing of the Professional Building in 1958. And to leave no doubt as to the bank’s presence in Phoenix, the company decided to add a rotating sign on an adjacent roof.

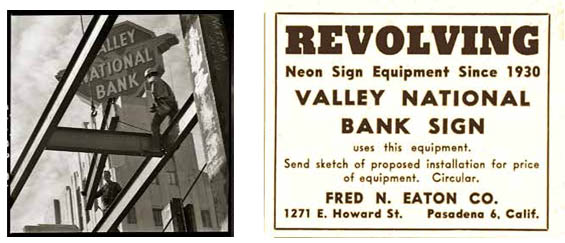

The Valley National Bank selected Myers & Leiber Sign Company, then Arizona’s largest sign firm, to construct the sign. In the process, the bank’s logo was updated by famed sign designer Glen Guyette, who worked for the sign company. “I had to redraw it; the eagle looked more like a chicken,” he recalls.

The sign’s steel frame was fabricated by the Allison Steel Manufacturing Company in Phoenix. Three colors of translucent porcelain enamel panels with six-foot-tall letters composed the sign’s face, which was illuminated by white and gold neon tubing. “It was one of the few porcelain signs ever put up in Arizona,” says Guyette.

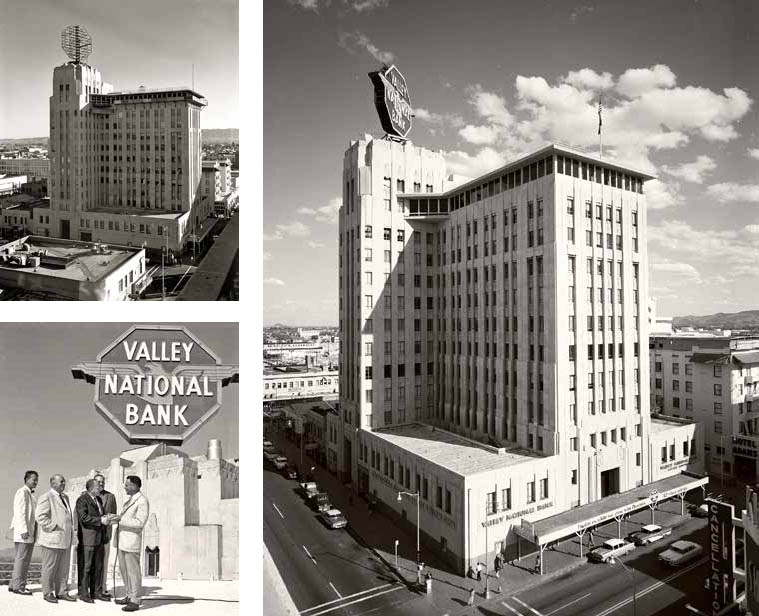

Top Left: Construction frame of the world’s largest rotating sign, January 1958. Bottom Left: Dedication ceremonies for the Valley National Bank sign, April 29, 1958. Right: Completed Valley National Bank sign atop the Professional Building, March 1958.

Constructing the 26-ton sign atop the 12-story building proved complicated.

The sign turned at 1.5 revolutions per minute and was controlled by an anemometer to prevent overloading during high winds. “When the wind blew, the three-story-high sign would turn into the wind and the motor would stop,” Guyette says. “The wind pressure on it was fantastic.”

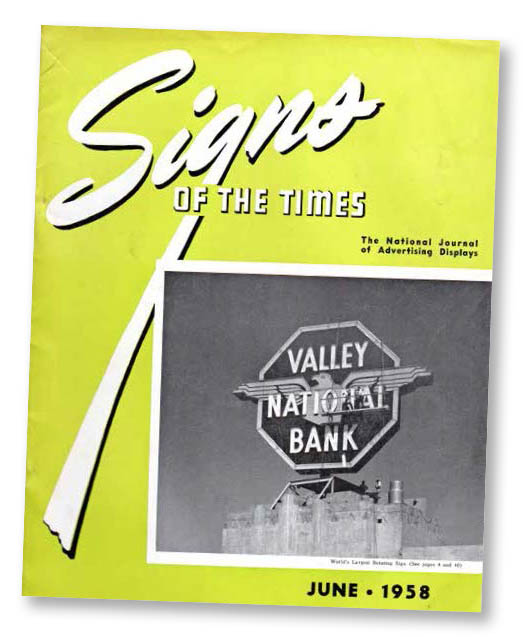

Radio and television stations broadcast the sign’s dedication on April 29, 1958. The huge sign, visible from airplanes 10 miles away, was featured on the June 1958 cover of Signs of the Times. The industry trade publication heralded the Valley National Bank’s eagle as the largest revolving sign in the world.

Usually, several sign company employees worked together when performing maintenance on the sign. Workers accessed the sign itself using a trap door and interior ladder. The outer perimeter of the sign consisted of a channel that housed neon tubes.

“One afternoon I decided to service the sign by myself,” Glen Zwick, who worked for the sign company, recalls. “After climbing through the interior of the sign and out the top hatch, I inched my way across the octagon. Due to pigeon droppings, I lost my footing and started sliding down the side of the sign.”

Panicked, Zwick tried to grab the sign’s outer channel. Although unsuccessful, he managed to slow his fall enough to have a controlled crash on the eagle’s extended wing. “I sat there shaken, trying to regain my composure,” Zwick recalls. “I eventually made my way back up to the hatch and left the site. I never returned again without a helper.”

Signs of the Times cover, June 1958.

Signs of the Times cover, June 1958.

The Valley National Bank’s eagle stood perched above Phoenix a mere 14 years, until the bank moved across the street into the newly constructed Valley Center building in 1972. The bank subsequently disassembled and removed its neon eagle sign, and Phoenix lost one of its most recognizable landmarks.

Left: Revolving Neon Sign advertisement in Signs of the Times magazine, June 1958. Right: Valley National Bank seen from the adjacent Valley Center building, 1971.

AUTHOR INFO: In addition to his services to the SCA, Douglas Towne writes history columns for PHOENIX magazine, the Arizona Republic newspaper, and is editor of Arizona Contractor & Community magazine, a bi-monthly 80-page publication that covers the state’s construction history.

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2017, Vol. 35, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA