By Lyell Henry

By the early 1930s, Americans could hardly miss noting that something extraordinary and fascinating was happening on the nation’s roadsides. What they could readily see with their eyes was also validated by lengthy articles appearing in several high-toned magazines.

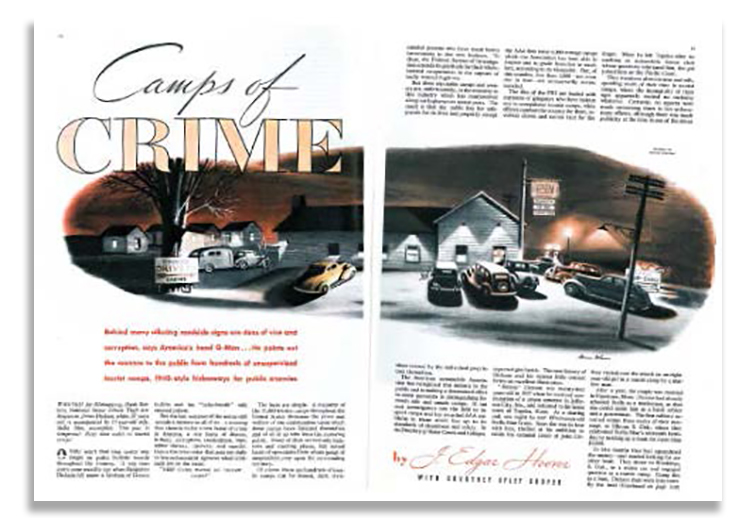

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s account of tourist camps as sinister, scary places in The American Magazine, February 1940, found haunting graphic expression in Stevan Dohanos’ accompanying illustration.

In the July 1933 issue of Harper’s Magazine, an article titled “Three Hundred Thousand Shacks” called attention to an estimated 30,000 tourist camps that had, within the space of only a few years, mushroomed along the highways of the United States. The article’s authors, John J. McCarthy and Robert Littell, heralded this astonishing development as “the arrival of a new American industry,” which they characterized as a product of “rugged American individualism” and welcomed as one of the few bright spots in an economy wracked by depression. They also saw tourist camps as reviving “the old fellowship of the road” and accommodating a “restless, pioneer, gypsy streak that lies at the bottom of most Americans.” Delighting in the diversity and whimsicality of these tourist cabins, courts, and cottages (most of them “free from the influence of art,” they noted), McCarthy and Littell presciently advised that, “before it is too late, someone with a camera and a passion for Americana should motor about the country collecting material for a monograph on the architecture” of these novel structures.

An equally celebratory account of the developments along America’s highways was “The Great American Roadside” in the September 1934 issue of Fortune magazine. (It was unsigned but known to be written by James Agee.) Agreeing with the foregoing writers that tourist camps offered “a new way of life” reflecting a deep-seated American “restiveness,” Agee concluded that the “American people have created the cabin camp because the hotel failed them in their new objective— motion with the least interruption.” These roadside businesses also had roots “deep in the homely quality of individual initiative,” he believed, and they provided their owners not merely with an income but also with “a sense of accomplishment, of having created something.” Agee’s peroration gave full vent to his enthusiasm and admiration: “The tourist camp is one sound invention that the American roadside has contributed to the American scene. And as an invention it is more satisfying than the hotdog.”

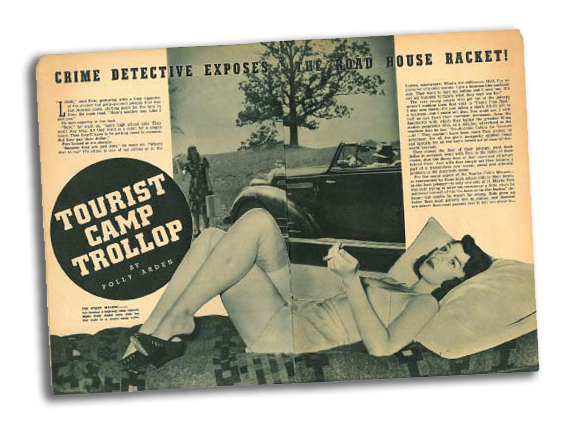

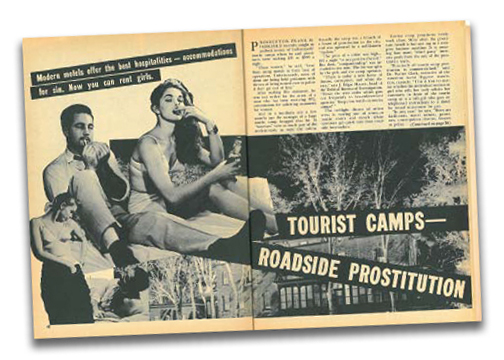

Polly Arden’s skewering of tourist camps in Crime Detective, December 1938, beat Hoover’s article into print by more than a year.

Within only a few more years, however, such soaring Whitmanesque paeans to the charms and virtues of the American roadside had begun to be challenged by much darker and more disturbing accounts. The tourist camps that had at first been hailed as delightful expressions of American character and genius now were as likely to be viewed as hotbeds of sordidness and immorality, even as “Camps of Crime,” the title of an article appearing in the February 1940 issue of The American Magazine. This was an influential article, too, because it not only got wide exposure in a mass-circulation journal but appeared under the byline of J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Hoover’s article (written “with Courtney Ryley Cooper”) limned a truly appalling picture of the roadside generally and of tourist camps in particular.1 The latter were “a new home of crime in America,” Hoover wrote, “a new home of disease, bribery, corruption, crookedness, rape, white slavery, thievery, and murder.” A majority—and Hoover made clear that he meant nearly all—of the 35,000 tourist camps that he claimed to be then in business along the highways “threatened the peace and welfare” of their communities and the traveling public.2 Gangsters favored tourist camps as hideouts and bases of operation, he counseled; “hence the terse order that goes out daily to law-enforcement agencies when criminals are on the loose: ‘KEEP CLOSE WATCH ON TOURIST CAMPS!’” Too, Hoover disclosed, tourist camps operated in conjunction with “Dine-and-Dance” roadhouses or nightclubs that were “little more than camouflaged brothels.” At these “spots of dubious entertainment,” located on the bleak and unpoliced outskirts of hundreds of small towns and cities, illegal drugs, booze, and gambling were readily on offer; lovers carried out illicit assignations; contemptible divorce detectives sneaked about plying their miserable trade; nomadic prostitutes, hitching rides with truck drivers, arrived from afar; and local “boys and girls, often from reputable families, [went] for a night of thrills.” Until there were much tighter controls on the operation of tourist camps, Hoover warned, Americans would continue to suffer such “pestilential conditions along our highways.”

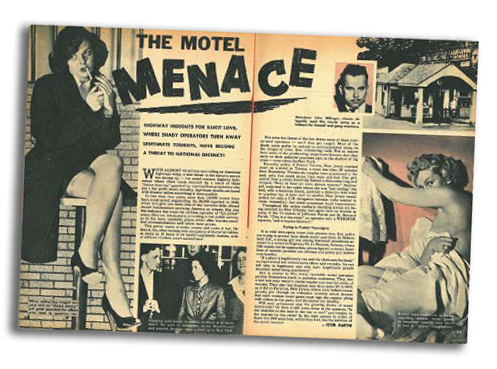

By the early 1950s, the “tourist camp menace” had become the “motel menace.” From Whisper, September 1953.

Coming from the nation’s top cop, Hoover’s words doubtless carried great authority, yet his main claims must have already been familiar stuff to most of his readers. Although his across-the-board condemnation of nearly all tourist camps went much too far, his claims and lurid account obviously held true for some or even many of them. In their 1934 otherwise-praising article in Harper’s, McCarthy and Littell had already acknowledged that “unfortunate things happen once in a while” at tourist camps (for the very reason that Hoover described aptly as the “easy privacy” found there), and they acknowledged that the “lowlier” camps were often run as “love nests.” Moreover, hotel trade associations, responding to competitive pressures, had done their part to darken the public’s view of tourist camps throughout much of the 1930s. That had also been a decade of lawlessness featuring notorious gangsters (such as Bonnie and Clyde, John Dillinger, and “Pretty Boy” Floyd), who often did hole up in tourist camps and sometimes engaged G-men in shoot-outs there, encounters that were widely publicized in the popular press.

Still using the antiquated term ‘tourist camps’ and relying on Hoover’s dated claims, this article in Off the Record Secrets, May 1964, brought a pathetic end to the pulps’ crusade to combat the “motel menace.”

As it happened, a segment of that popular press—pulp magazines of the “true-crime” and “true-confessions” genres—had already begun to carry articles purporting to document the “scandalous truth” about tourist camps and roadhouses. Indeed, a whole year before Hoover’s article was published, it had been scooped by “Tourist Camp Trollop,” a two-part exposé by Polly Arden in the December 1938 and February 1939 issues of Crime Detective magazine. Allegedly drawing on her own experiences (a beauty contest winner from Iowa who sought a movie career in Hollywood but ended as a prostitute roving tourist camps), Arden covered most of the points Hoover later made in his article, including the charges that tourist camps were “the headquarters for a sort of migratory underworld” and that only a “pitifully small minority” of them were decent, legitimate businesses. “You must be conscious of the Great American Roadside,” Arden warned her readers, because there has appeared “a tremendous new moral, social and criminal problem in the American scene . . . the Tourist Camp Menace.” Similar warnings were conveyed in an unsigned serialized narrative titled “Dine and Dance Girl” appearing in True Story magazine in the winter of 1939-1940 (by chance, reaching print at the same time as Hoover’s article) and that purported to expose “The Sin along Our Highways.” Hoover’s article added nothing, beyond the authority of his name as director of the FBI, to the force or the particulars of the harsh indictment found in both of these sensational personal accounts.

Americans obviously had more pressing matters during the 1940s than the “tourist camp menace,” but apparently so deep-seated was this social ill that it outlasted both the Great Depression and World War II and ignited a revived campaign of exposure by the pulp magazines in the early post-war years. However, the evil to be scotched became the “motel menace” in recognition of the rapid spread after 1950 of the new term for the latest phase of roadside accommodations.

The pulp magazines blasted away at the alleged menace along the highways throughout the 1950s and even into the 1960s, including in their ranks representatives from two more pulp genres—“confidential-secrets” and “real-man” magazines.3 The obsessive focus of attention in articles was the illicit sex (mostly the “couples trade” of unmarried lovers’ trysts, but also prostitution) allegedly befouling the roadside in so-called “hot pillow” operations. Although these articles (unlike those by Hoover and the earlier pulp writers) usually conceded that most motels were legitimate businesses run by honest operators, the illegitimate ones apparently still remained a social problem of immense magnitude. Some titles of articles and places of publication give the flavor of this latest chapter of the great crusade: “Motel Confessions,” Man to Man: The Stag Magazine, April 1953; “The Sheriff and Waco’s ‘Motel Girls,’” Male, June 1953; “The Motel Menace,” Whisper, September 1953; “My Night in a Motel,” My Confession, December 1953; “Sex a la Motel,” Official Police Cases, October 1955; “Roadside Short-Order Sin: Motels,” Front Page Confidential, March 1960; “Caught in a Cheap Motel,” My Confession, August 1960; “Motel Mates: The Secret I Could Not Bury,” True Romance, April 1963; and “Tourist Camps—Roadside Prostitution,” Off the Record Secrets, May 1964.4

In the 1950s, the crusade by pulp publications against the “motel menace” was joined by pocket-sized paperback novels sold in drug stores and news stands. In truth, these books were soft-core porn, but perhaps that simply indicated that the “motel menace” was morphing into something more alluring, and therefore far more insidious, than the earlier tourist camps had been. Novelistic treatments presumably were better suited than brief articles to exposing the new guises of immorality that lay behind the glamorous facade of that latest roadside phenomenon called the motel. However, some of the earliest of these novels exhibited the confusion that was still widespread about what was a motel. A novel exploiting the word “motel” in its title might still stage all its action in what had always been known as a tourist camp or cabin camp—in other words, nothing was changed but the name. Too, the immoral goings-on described in these early novels could fall far short of reflecting any new kind or new level of sophistication connected with the advent of motels. In their pages, unglamorous people behaved in low-class ways in a familiar sleazy roadside setting.

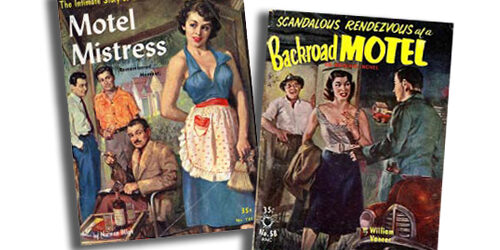

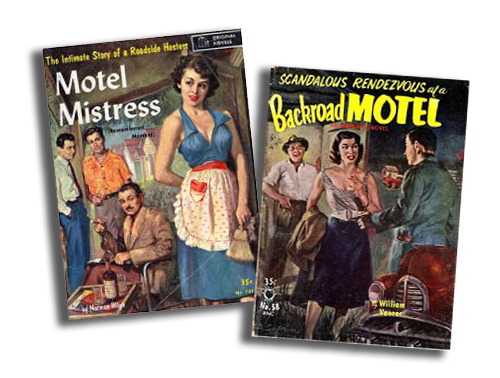

The motels depicted in these 1954 book covers are shacks, which share with their occupants a palpable aura of sleaziness. Note the bottle of booze worked into each scene, either onto a table or into a coat pocket.

The covers of two novels published in 1954 graphically capture the reality of these early so-called motels; in spite of the books’ expropriation of the new word for use in their titles, everything depicted is straight out of J. Edgar Hoover’s description of tourist-camp sordidness more than a decade earlier. In Backroad Motel (Croydon Books) by William Vaneer, for example, an ask-no-questions proprietor smirks, keys in hand, as he prepares to escort a young (and presumably unmarried) couple arriving for a “scandalous rendezvous” to one of his dismal small shacks, an example of which can be seen in the distance. The cover of Motel Mistress (Original Novels) by Norman Bligh shows a similarly seedy scene, in which three traveling men, one smoking a cigar and drinking whiskey, leer at the “motel mistress” (whatever that is), who does her work in a revealing summer dress and throws a come-hither look in the men’s direction. Here again, the so-called motel is really only a cabin camp, some of whose cabins are depicted in the background.

With the advent of the 1960s, novels of the soft-core porn variety purporting to explore new aspects of the “motel menace” reached a more up-to-date understanding of what a motel was. However, the motels described usually were not modest Mom-and-Pop operations but rather larger-scale highway complexes offering swimming pool, restaurant, and cocktail lounge in addition to a luxuriously appointed room for the night—in other words, perfect incubators of new dimensions of sexual depravity. Descriptive blurbs taken from the covers of some of the novels provide a fair indication of the novels’ new muckraking targets.5

Dean McCoy’s Sexbound (Softcover Library, 1965), for example, purports to be “a novel strange, savage and wholly frank—grappling with the problem of infidelity created by America’s roadside inns”; it also gives “warning that those who seek illicit adventure along the highway may find it, but only at great peril.” For its part, Curt Donovan’s Witch with Blue Eyes (Beacon Signal, 1962) takes readers “behind the doors of the new American phenomenon—the plush roadside motel” and exposes “what goes on behind the flashing neon signs of motels along America’s super- highways—where scandal is often covered by a plush exterior.” Orrie Hitt’s Motel Girls (Beacon, 1960) looks at “the seamier side of the motel business” and explores “the reactions of unwary girls to the motel’s temptations.” Of special concern in Jim Layne’s Girl in the Motel (Beacon Signal, 1963) is “a new kind of passion paradise—lush oases at the desert motels” and “the new breed” of sinners spawned there. And from the back cover of Jay Carr’s Motel Wives (Beacon, 1963) comes the following précis: “Lush motels with barside pools are a familiar part of the American scene today. This shocking novel tells in detail what really goes on in some of those highway love-nests.”

Other motel novels published in the early 1960s that also purported to probe behind the glitter of the new highway hostelries included Motel Girl (1960), Motel Hostess (1961), The Motel (1961), Motel Mismates (1961), Motel Trap (1962), Motel Marriage (1962), Sign Here for Sin (1963), That Motel Weekend (1964), and Campus Motel (1965).6 After 1965, however, at the very same time that the pulp magazines seemed to cease publishing articles exposing the “motel menace,” the gusher of novels serving that same lofty cause appears also to have dried up.7 Had the dreaded menace withered away or been vanquished at last?

Far more likely, motel novels disappeared because their readers deserted them. By then most Americans must have used motels and found them to be perfectly ordinary, safe, and convenient places (especially ones in the new national motel chains), and in those new circumstances of familiarity, representation of most motels as sexual playgrounds or outposts of California-tinctured hedonism surely would be a much harder sell. Probably, too, there were no longer many readers who could be roused by the motel novels’ exposés—or, stated another way, by the late 1960s these novels were pretty lame specimens of pornography. In fact, their “shocking” claims and “frank” descriptions of immoral activities on the roadside must by then have seemed positively quaint, stilted, or even laughable. Popular attitudes about those sexual activities were changing rapidly as was public acceptance of pornography, which soon reached a previously unimaginable flowering under an expanded First Amendment protection. Nothing that the motel novels had presented in the early 1960s came anywhere close to what was on tap in books, magazines, and films after 1970.

By the early 1960s, both the motels and their occupants featured in sleaze motel novels had acquired a more up-to-date and glamorous appearance, as shown on the covers of these novels.

As for the pulp magazines, any continuing interest they had in motels was likely to be only incidental to an apparent new focus on documenting features of the so- called “sexual revolution” then underway. For example, “We Ran a Motel for Swappers Only,” published in the May 1970, issue of Male, was not a confessional or an exposé but rather a non-judgmental case study of an alleged “new West Coast sex trend.” Also offered up in the guise of value-neutral social science was “Girls Who Take Sex-and-Sightseeing Car Holidays,” an article appearing in the April 1971 issue of Men that reported—without a hint of moral outrage—on another alleged new trend in the uses and users of motels.

From their start in the 1920s, tourist accommodations out on America’s highways were foredoomed to acquire a shady reputation; as places of “easy privacy,” inevitably they would be put to uses considered scandalous by a culture that, even more than half-way through the 20th century, still exhibited a pronounced moralistic streak. It was this same moralistic cultural milieu that opened the way for pulp books and magazines to serve up mildly titillating stuff about motels under the pretext of exposing a great evil and thereby defending traditional morality.

Deep-seated though the American obsession with “the sin along our highways” had been, however, the pulps’ milking of that theme was no longer plausible once the assault on long-standing sexual taboos got going in the late 1960s and intensified in the early 1970s. But another circumstance was of even greater moment in knocking the wind out of the old crusade against the “motel menace”: in those same years, the more open, free-wheeling “frontier era” of the American roadside came to a close, yielding to a new phase of development. Increasingly, national corporations would become the dominant actors along America’s highways, and the motels they built were endowed with an aura of respectability that had not been generally enjoyed by highway hostelries in the Mom-and-Pop era.8

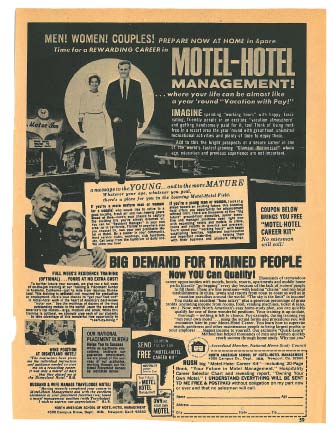

Another tell-tale item appearing in the April 1971 issue of Men cited above nicely betokened this dawning of a new day on the roadside—to wit, a full-page ad proclaiming a “big demand for trained people” in motel management and offering training by correspondence for readers who sought a rewarding career in “one of the world’s fastest growing ‘Glamour Businesses.’” Could there have been better evidence than this that both the “motel menace” and the pulps’ great crusade to expose it were no more?

This ad in Men, April 1971, offers further evidence that the pulps’ perceptions of a “motel menace” had ended. Note the absurd description of the alleged easy life of a motel manager.

Endnotes

1 This was one of 16 articles written by Cooper in association with Hoover and published in The American Magazine during the 1930s, according to Bryan Burroughs, Public Enemies: America’s Greatest Crime Wave and Birth of the FBI, 1933- 34 (Penguin, 2004), p. 517. Burroughs describes Cooper as “a flamboyant freelancer” who was “a

specialist in pulp crime stories” and whose articles on Hoover were crafted to depict the FBI director as “the master detective” standing “at the nexus of the War on Crime.” Thanks to Cooper’s PR effort, as well as the FBI-glorifying Hollywood movies of the 1930s, Hoover’s pronouncements about tourist camps doubtless had real heft, even though his characterization of most of them as “camps of crime” surely went beyond the truth.

2 Of those estimated 35,000 tourist camps, Hoover allowed that only “hundreds” were “run by honest, alert, civic-minded persons.” Hoover’s 35,000 estimate, made in 1940, jibes with the 30,000 estimate offered by McCarthy and Littell in their 1933 Harper’s article, but neither article identified a source. In 1992, Tania Werbizky tracked down estimates of numbers of tourist camps and courts recorded in some other contemporary publications. Her compilation, titled “How Many Tourist Camps and Courts Were There?“ (SCA News Journal, 2:2, Fall 1992, p.22), disclosed a wide range of estimates, some close to Hoover’s but others much lower. Lower figures (9,848 tourist courts in 1935, and 13,521 in 1939) were also reported by the United States Bureau of the Census, according to Peter B. Dedek, “From Cozy Cabin to Two Beds and a Television: Progress and the Evolution of the Vernacular Motel Room, 1926-1970,” SCA

Journal, 29:2, Fall 2011, p. 10. The actual number of tourist camps and courts in the 1930s appears to lie beyond a definitive estimate.

3 These two labels of pulp genres, as well as the two specified previously, are of my own concoction, but they appear to jibe fairly well with terms used by pulp-magazine collectors (although the latter might substitute “men’s-adventure” for my “real-man” magazines). Here I should also note that my conclusions in this article are based on study of publications mostly obtained from eBay auctions during the past five years. Examination of larger holdings of pulp magazines, or even a scientific sampling of the vast number of such magazines published from the 1930s through the 1970s, might produce sturdier conclusions. However, where are those large caches of pulp magazines, and how accessible are their articles? As for scientific sampling, how could that be done in the absence of a known universe of relevant pulp magazines? Rather than throw in the towel in the face of these methodological difficulties, I assembled from eBay auctions much relevant material (some productive search entries were “motel sleaze,” “motel book,” and “motel magazine”). Whatever distortions or gaps in data might result from this procedure, I’m convinced that the items collected do disclose real features and definite temporal patterns of the crusade by the pulp magazines against the “motel menace.”

4 The final article in this list must truly have been the last gasp of the pulps’ crusade against the “motel menace.” Not only have I found no more recent articles from that crusade, but the content of this article was already stale and hackneyed by the time of its publication in 1964. Some of the information and claims in the article were taken directly from J. Edgar Hoover’s 1940 article! Notice, too, the use in the article’s title of “tourist camp,” even though by then it was already an archaic term.

5 After reading some of these novels (a grim and tedious exercise done as a scholarly duty), I concluded it was not necessary to read the rest of them in order to get their take on the “motel menace.” For that purpose, the blurbs (and art work) on the front and back covers are sufficient. The novels I read didn’t necessarily deliver on the grandiose claims found in those blurbs, but the motels usually were presented as chic new places of accommodation of illicit sex.

6 Not all, or maybe not even most, novels set in a motel or having that word in their titles qualify as motel novels, as I use that term here. The very purpose of the ones to which I apply the term was exploitation of the notion of motels as centers of illicit sexual activity. These novels also were cheaply produced paperbacks that had very well done front covers bearing high-octane sexual content in the form of calendar-art images of women (images much admired by paperback collectors as so-called “good girl art”). Most of these novels seem to have been published by houses specializing in “adult fiction”—for example, Beacon Signal Books, Softcover Library, and Bedtime Books—and offering huge lists of adult titles, of which the motel novels were only a minuscule fraction. Confined as they were to the short time period of the 1950s and early ’60s, the motel novels, like all the other offerings of these publishers at that time, never could rise above a soft-core level of pornography.

7 As a matter of strict logic, I can’t claim more here than that my eBay searches have not yielded any articles or novels addressing the “motel menace” published after 1965, but as I explain in my text, I believe the absence of evidence does, in this case, indicate reliably that the great crusade to expose the “motel menace” had at last run out of steam.

8 For an excellent discussion of the cultural context in which both Mom-and-Pop highway hostelries and an obsession with illicit sex and an alleged “motel menace” could prevail on the roadside for over three decades but then begin a fast decline, see Chapter 3, “Mom-and-Pop Enterprise,” pp. 57-89, in John A. Jakle, Keith A. Sculle, and Jefferson S. Rogers, The Motel in America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996). The authors highlight the clash that came to the fore in the 1920s between proponents of traditionalist and modernist views not just about sexual matters and other conventional moral issues but also about the acceptability of an emerging consumer culture. As the corporate phase of roadside development rose to dominance in the 1960s, the authors argue (p. 79), “Mom and Pop found themselves victims of the very consumer culture in which their hopes and industry had taken root.” Andrew Wood (Ph.D., Ohio University, 1998) is an associate professor in the Communication Studies department at San Jose State University. Dr. Wood is author of Road Trip America: A State By State Tour Guide to Offbeat Destinations (Collectors Press) and New Yorkʼs 1939-1940 Worldʼs Fair (Arcadia). He is also co-author of Motel America: A State by State Tour Guide to Nostalgic Stopovers (Collectors Press, with his wife Jenny) and Survivor Lessons: Communication Issues Under a Watchful Eye (McFarland, with Matthew Smith).

Did you enjoy this article? Join the SCA and get full access to all the content on this site. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Spring 2012, Vol. 29, No. 1. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA