The Diner of Tomorrow…Today!

A Look at the Literature and Marketing Devices that Kept the Industry Moving Forward

By Richard J.S. Gutman

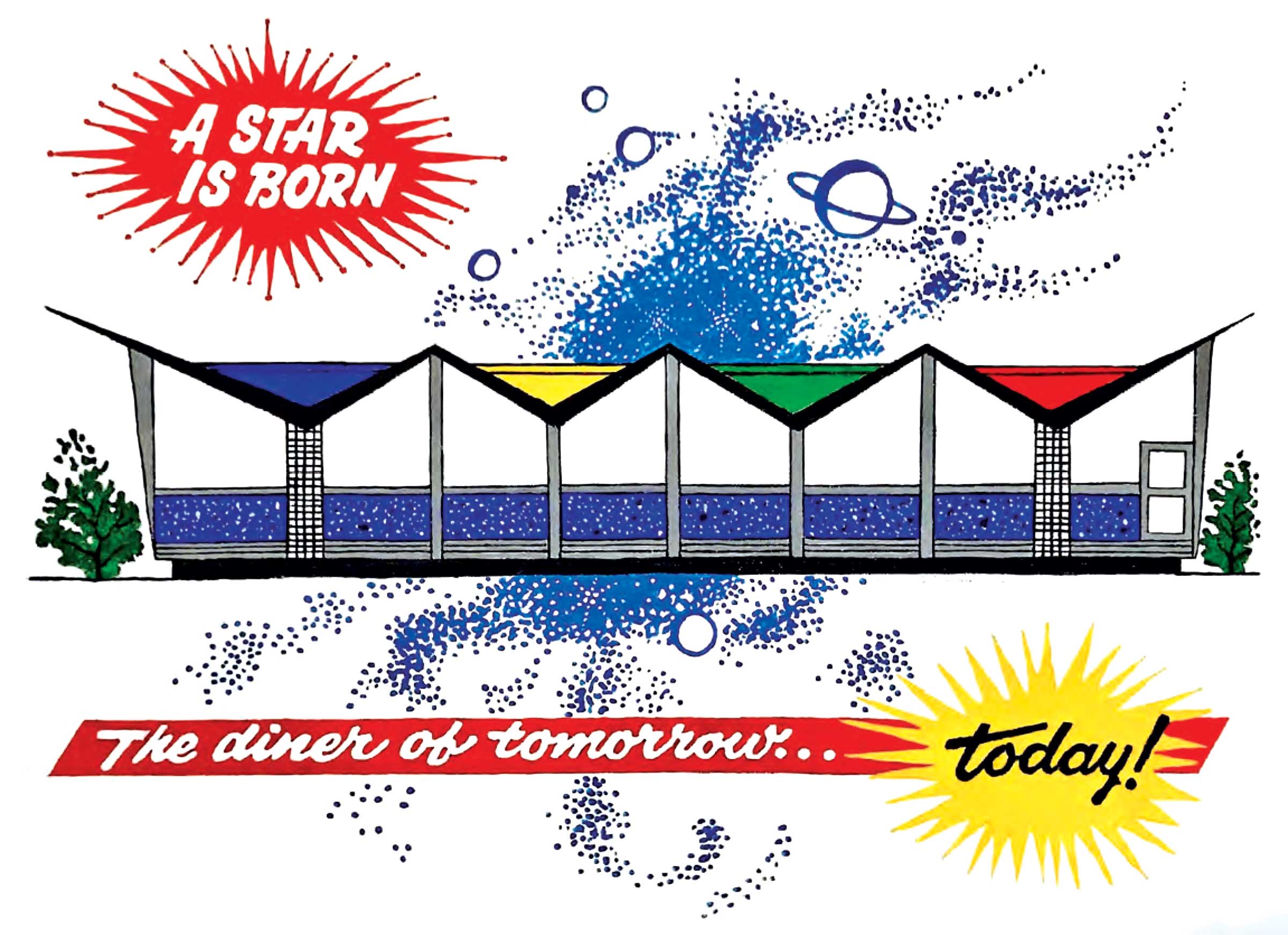

A Star is Born, acrylic on canvas, 16 x 20-inches, by Richard J.S. Gutman, 2002. This painting recreates a Manno Dining Car Co. matchbook that advertised a late 1950s futuristic diner style.

Personal collection of Richard J.S. Gutman.

On the night of January 10, 1917, Patrick J. Tierney—the man who brought the toilet inside diners—ate at one of his lunch cars while trying to make a sale to Mrs. F. E. Benham of Yonkers, a prospective buyer. Later that night, “Pop” Tierney, as he was affectionately known, complained of stomach pain and took to his bed, dying soon after. The cause was given as acute indigestion. Thus, the founder of the largest, most influential lunch-car building concern of the time paid the ultimate price: giving up his life at age 51 to sell a diner.

Diner manufacturers certainly employed less dramatic methods in their never-ending quest to convince customers to purchase their products.

Because diners were buildings that looked like no others, the structure stood as an advertisement for someone who wanted a meal and an entrepreneur looking for a business opportunity.

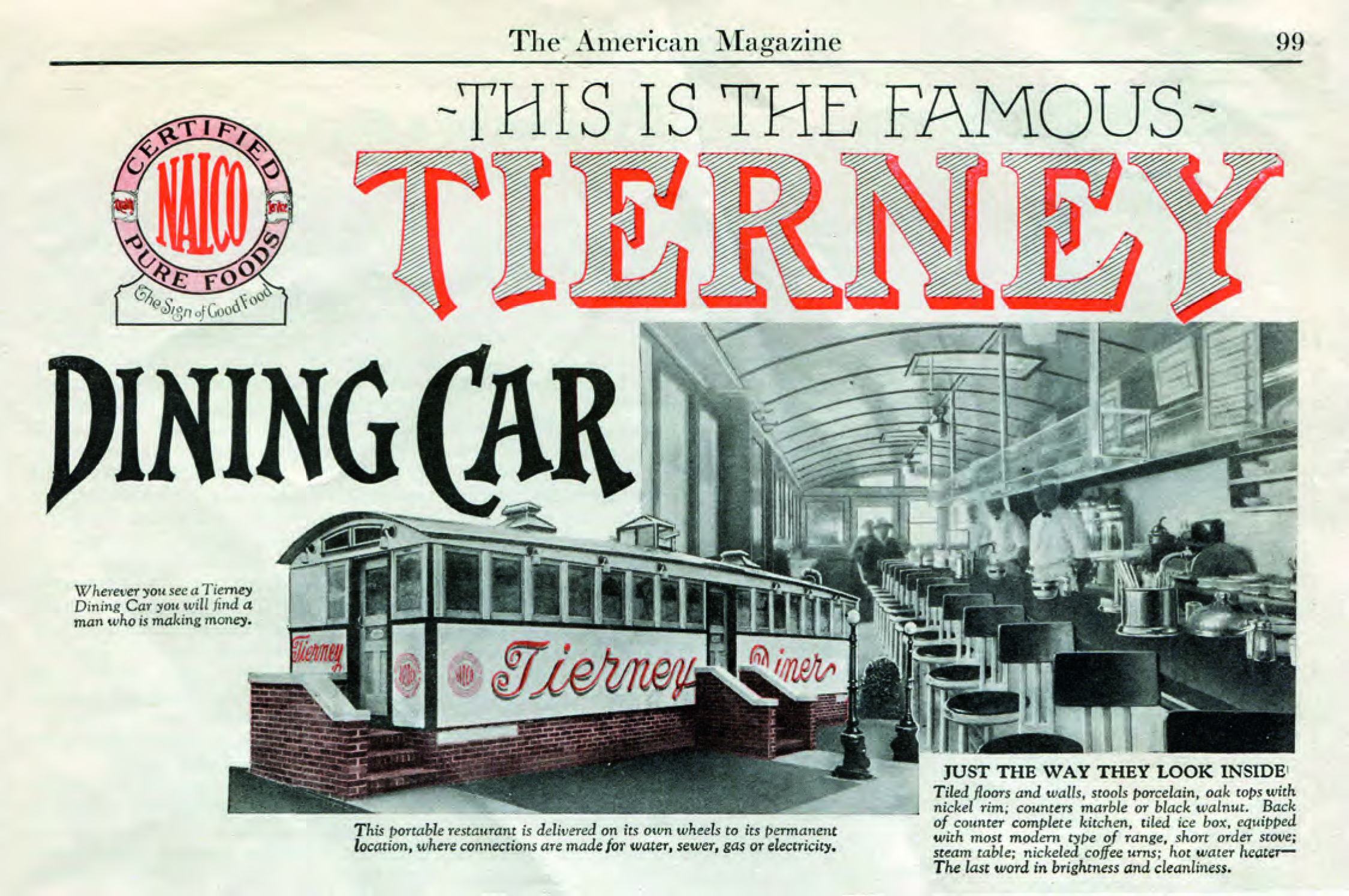

Tierney ad, 1926.

The Henry Ford, Richard J.S. Gutman Diner Collection.

In the 19th century, when the diner’s forebears, the lunch wagon, first appeared at night on street corners, the concept was a novelty and a success. Would-be operators contracted with wagon builders to construct restaurants on wheels. Eventually, the first patent was awarded in 1891 to Charles H. Palmer, whose factory offered “fancy night cafés” and “night lunch wagons.” He advertised in the Worcester [MA] City Directory.

An early competitor in Worcester, Thomas H. Buckley, produced the first known catalog. This publication featured various lunch wagon designs and supplies, including decorative flash glass windows, French plate mirrors, linoleum flooring, and a standard fire pail. Also offered were dishes and cutlery for the customer and Sabatier knives “specially imported for Lunch Wagon Business” for the operator.

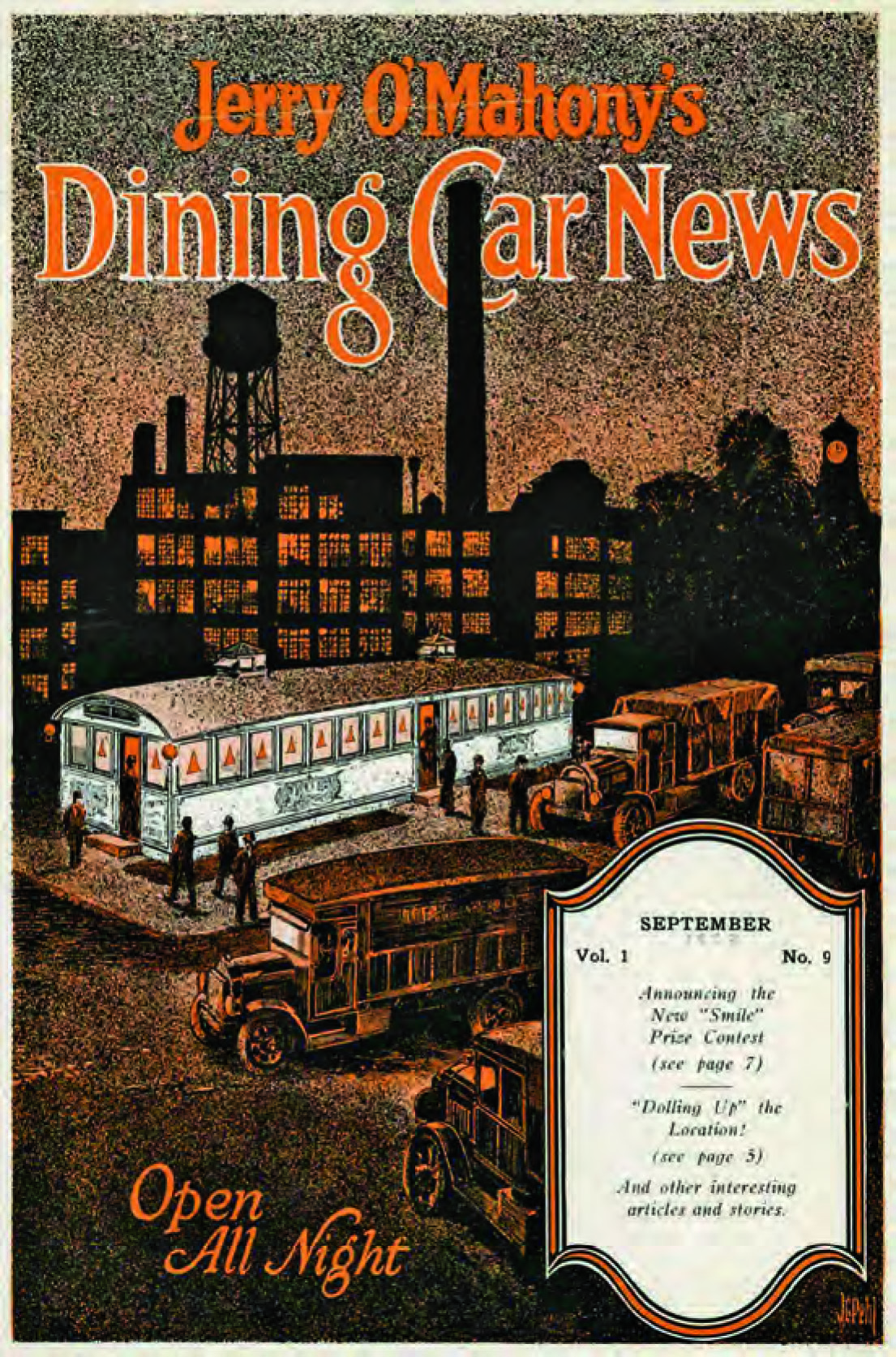

Jerry O’Mahony’s Dining Car News, 1927.

The Henry Ford, Richard J.S. Gutman Diner Collection.

Thirty-two-year-old Jerry O’Mahony broke into the business in 1913 in Bayonne, NJ, building two lunch wagons that year. O’Mahony issued his first catalog in 1922, claiming, “From that day to this, he has never caught up with the demand although he has repeatedly enlarged his facilities.” At that time, P. J. Tierney Sons, Inc. and the Worcester Lunch Car and Carriage Manufacturing Co. were the only significant builders in the industry.

Until he sold the company nearly a half-century later, O’Mahony could rightfully claim, “In Our Line, We Lead the World.” Six different catalogs, distributed until World War II shut down diner manufacturing, described various models, showed typical locations, touted success stories, and included testimonial letters from satisfied customers.

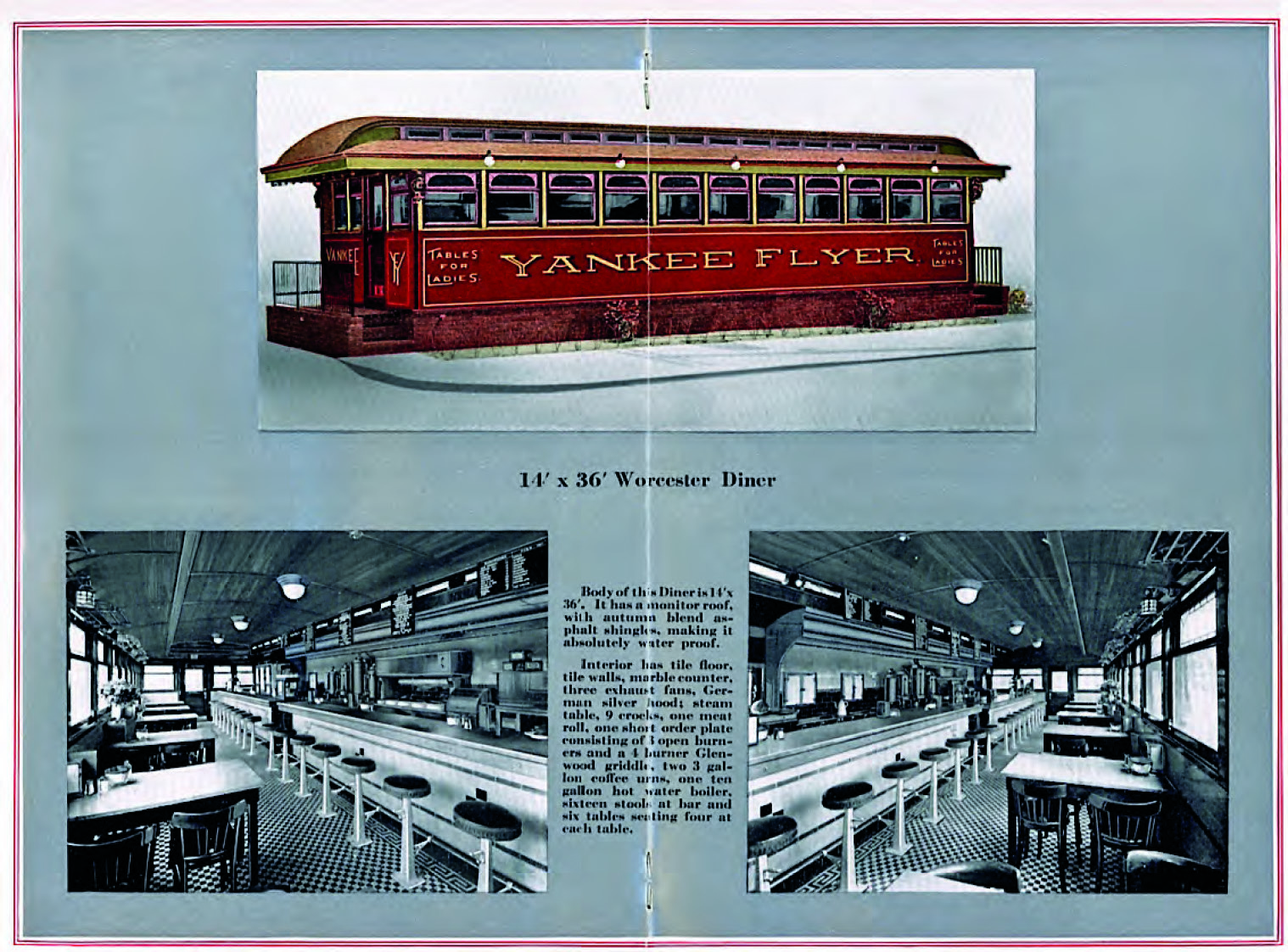

Worcester Lunch Car Company catalog, center spread, c. 1930.

The Henry Ford, Richard J.S. Gutman Diner Collection.

The factories of Tierney and O’Mahony were only 40 miles apart. Both published magazines for promotional purposes. Tierney Talks and Jerry O’Mahony’s Dining Car News were “devoted to the interests of the Dining Car Owners” and would-be owners. Tierney went beyond, operating the Tierney Training School in a diner next to their plant in New Rochelle, NY.

Here, those new to the business could attend, in the words of a writer for Popular Science Monthly, “one of the strangest schools in the world … where future proprietors are taught to wash dishes, scrub floors, cook, bake, order provisions economically, serve good meals without waste, and a hundred and one secrets of pleasing the eating public.”

Richard J.S. Gutman is the leading authority on the history and architecture of diners. In 2019, he donated his collection and archives to The Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan. The museum features, through March 16, 2025, the exhibition Dick Gutman, DINERMAN, an eclectic assortment of more than 1,000 artifacts, including memorabilia, scale models, furniture, fragments, and a photographic history of diners through time.

There’s more! To read the rest of this article, members are invited to log in. Not a member? We invite you to join. This article originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2024, Vol. 42, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Articles Join the SCA