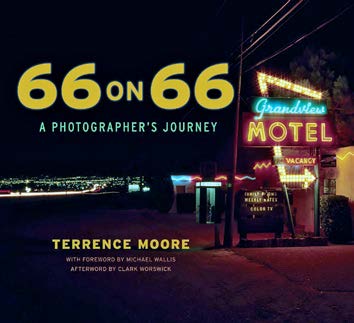

66 on 66: A Photographer’s Journey

By Terrence Moore

Tucson, Ariz.: Schaffner Press, 2018

144 pages; 10 x 11.5 inches, $27.95 hardcover

Reviewed by Douglas C. Towne

Terrence Moore is a talented photographer, and his gifted eye is apparent in 66 on 66, a coffee table book that is his latest contribution to the lore of the Mother Road. The book’s 66 images are more than a display of Moore’s photographic prowess, however. They synergistically work together to create what contributor Clark Worswick describes as “a memorial to a vanished time and place.”

Terrence Moore is a talented photographer, and his gifted eye is apparent in 66 on 66, a coffee table book that is his latest contribution to the lore of the Mother Road. The book’s 66 images are more than a display of Moore’s photographic prowess, however. They synergistically work together to create what contributor Clark Worswick describes as “a memorial to a vanished time and place.”

What makes this offering unique is that this project wasn’t something Moore started recently to capitalize on the Route 66’s popularity: he grew up along the road and has been taking professional photos of the legendary migration route for almost 50 years. “Terry Moore is the Dean of Mother-Road photographers,” author and contributor Michael Wallis says.

Moore spent his childhood in Claremont, California, in the 1950s, a then bucolic town of citrus groves and eucalyptus-lined streets. The famed highway was close to his house. “I rode my bike on 66, went to high school on 66, bought my first car—a 1932 Ford—on 66,” he writes. And when Moore moved away after high school, he found himself right next to the highway in Albuquerque, living in an adobe house near Old Town.

It was during Moore’s New Mexico period that he started accumulating photos featured in the book, including one of my favorite selections, “700 Miles of Desert.” This image, taken in 1971, received exposure in Michael Wallis’s seminal book, Route 66: The Mother Road (1990). The iconic photo captures a wall of the abandoned Kiva Trading Post west of Albuquerque, illustrated with a sweating skull admonishing travelers to be prepared for the upcoming scorching desert drive by offering “Water Bags,” “Thermos Jugs,” and “Ice.”

This is among a handful of images that will likely seem familiar to many readers. Besides contributing to Wallis’s book, Moore has taken some of the most famous photos of America’s Main Street. You may have seen his Route 66 photos in publications including Smithsonian, American Heritage, Rolling Stone, Arizona Highways, and The New York Times.

However, 66 on 66 is the first time that Moore’s photos of the highway have been assembled into a single volume. He covers Route 66 from Missouri to California, omitting the stretch in Illinois; many of the images are from New Mexico and Arizona. Besides the requisite gas, food, and lodging shots, Moore includes eclectic subjects such as the Regal Reptile Ranch in Alanreed, Texas, that promises “Live Poison Rattlesnakes Shown Today” and a stucco dinosaur devouring a scantily clad female mannequin near Holbrook, Arizona.

The book is aided by contributions from two writers. Wallis, who provides the book’s brief foreword, lavishes praise on Moore’s work with the camera, comparing it to “Hendrix or Clapton making love to a guitar.”

The compelling afterword is by Worswick, a fellow photographer who has known Moore since the mid-1960s. Interestingly, he draws connections from Moore’s roadside documentation to that of Dennis Hopper and Ed Ruscha, pioneering photographers in southern California during the 1960s. Worswick writes what they were all pondering back in the day: “In the future would anyone ever be interested in what America had been in its earlier versions?”

The response to their work has been an enthusiastic, yes! And the value of their contributions has only increased, as so many of the images contained in the book have been lost to time.

While the photos and writing are top-notch, my one disappointment with 66 on 66 is what it doesn’t include. Every other page lists only the photo’s subject matter, location, and date taken. That’s a LOT of unused white space. The book doesn’t necessarily need more pictures, but it would have been interesting for Moore to tell asides or stories behind the images—and surely he must have some good ones—along with the photo information.

For example, on one of his Route 66 photo assignments with Rolling Stone in 1984, Moore and New York Times writer Iver Peterson each chipped in $750 and bought a ’59 Cadillac they nicknamed “The Blue Cadoo” and headed West. Surely the statute of limitations has passed for any juicy stories during their ventures, which he could relate in the book.

The big question with Moore’s book is, given numerous commercial archeology photography books that are available is, why purchase another one? Worswick provides a good reason, and I agree: “Moore’s work rises to incandescence in its description of an evanescent moment, when vibrant vernacular art in neon and paint grew up, then flourished alongside The Mother Road of America,” he writes.

What SCA member wouldn’t covet such a treasure?

Douglas C. Towne is the editor of the SCA Journal. He once walked 8 miles along Route 66 during snow flurries in St. Louis to enjoy frozen custard at Ted Drewes. Doug was heartbroken when he realized the stand lacked interior seating, and he would have to eat it outside.

This book review originally appeared in the SCA Journal, Fall 2018, Vol. 36, No. 2. The SCA Journal is a semi-annual publication and a member benefit of the Society for Commercial Archeology.

More Book Reviews